India lags many of its south Asian neighbours on the human development index (HDI) primarily because of inequalities, said a recent report by the United Nations Development Fund. These inequalities, in turn, hamper India’s economic growth.

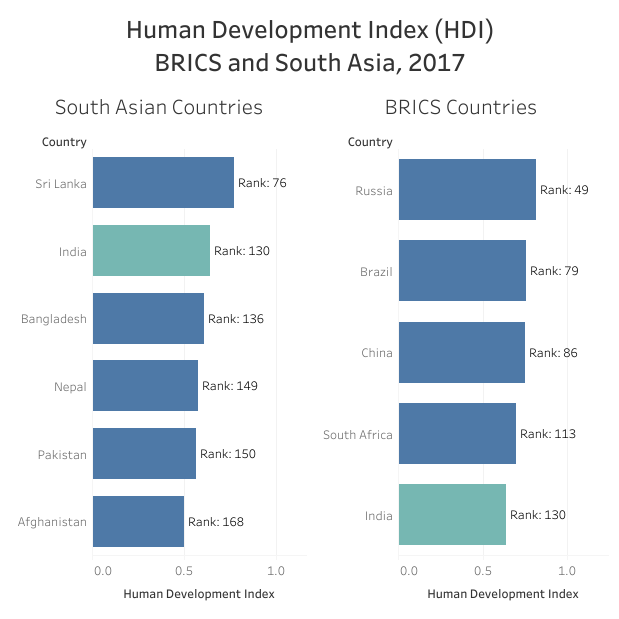

India ranked 130 out of 189 countries on the 2018 HDI index with a score of 0.640 which places it in the “medium” category of development. It fared worse than Sri Lanka (HDI 0.77, rank 76) and China (0.75, 86) but better than Pakistan (0.56 and 150), Nepal (0.57, 149) and Bangladesh (0.68, 136).

Source: 2018 Statistical Update, Human Development Indices and Indicators | Courtesy: IndiaSpend

India lost out 26.8 points on the index due to inequalities while the south Asian average for this factor is 26.1 points. Since human development index is driven by health, education and income, India would have to focus on excelling on these fronts to progress economically and reduce inequalities.

Related article: Addressing inequality in India

If India plans to double its economy to $5 trillion (Rs 350 lakh crore) by 2022 as Prime Minister Narendra Modi stated in August 2018 and grow at 8% per year as he predicted, it will need to invest more in health and education.

Consider this: Despite being the sixth largest economy in the world, with a gross domestic product (GDP) of $2.59 trillion (Rs 180 lakh crore), India accounts for about 30.8% of world’s stunted children. Not just short for their age, but one in five children in India is also wasted and underweight. Undernourished children struggle to stay healthy and find it hard to catch up with their peers in classrooms and at workplace.

Malnourishment may have cost India more than double of what was spent on health, education, and social protection schemes.

Malnourishment may have cost India upto $46 billion (Rs 3.2 lakh crore) in terms of income opportunities lost which is more than double of what India spent on health, education and social protection schemes in 2018-19 Union budget ($21.6 billion or Rs 1.38 lakh crore).

Indians work for just 6.5 years at peak productivity (compared to 20 years in China, 16 in Brazil and 13 in Sri Lanka), and India ranks 158th out of 195 countries in an international ranking of human capital published in medical journal The Lancet, IndiaSpend reported in September 2018.

“Our findings show the association between investments in education and health and improved human capital and GDP–which policymakers ignore at their own peril,” said Christopher Murray, director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington, author of the study.

IndiaSpend analyses these gender and income inequalities and offers solutions:

Gender imbalance

There were 919 girls born for every 1,000 boys in the last five years–the numbers are worse for urban areas (899) than rural areas (925)–which shows a male preference, showed National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) 2015-16.

Also, when it comes to literacy, women compare poorly (68.4%) with men (85.7%). Only 35.7% women completed more than 10 years of schooling, the survey showed.

While boys and girls had almost the same enrollment rate in school till age 16, by the time they turned 18 significant differences started showing up. And while both girls and boys struggled to do simple tasks like counting men, telling time and adding weights, girls performed worse, showed the 2017 Annual Status of Education Report.

Photo courtesy: Arjun Swaminathan

Made to focus on domestic chores, more than one in four girls got married before 18 years of age (26.8%). Her status after marriage remained poor–one in two non-pregnant women was anaemic (53.2%), one in four was underweight (22.9%) and one in three married women faced spousal violence (31.1%), showed NFHS-4.

Despite being more educated than before, Indian women aren’t working as much. In 2013, women above the age of 15 accounted for only 27.2% of India’s workforce–as compared to men who comprised 78.8%–and down from 34.8% ten years before, IndiaSpend reported in August 2017.

India’s performance on gender indicators is worse than its neighbours’–India ranked 127 out of 189 on UNDP’s gender inequality index, lower than Nepal (118), China (36), Sri Lanka (80) but higher than Bangladesh (134) and Pakistan (133).

Related article: Time poverty: The key to addressing gender disparity

Widespread inequality

India is one of the most unequal countries in the world with the top 10% controlling 55% of the total wealth against 31% in 1980, according to the 2018 World Inequality report. The bottom 50% control only 15.3% of the total wealth. The report shows that while the wealth of top 1% has been increasing since 1980s, the wealth of bottom 50% has been sliding.

Certain castes and communities are at more disadvantage than others. Muslims and Buddhists have the least share of assets and it has declined from 2002 to 2012, showed the 2018 Oxfam India report.

Scheduled tribes, despite accounting for 8% of India’s population, account 45.9% share in the lowest wealth group, IndiaSpend reported in February 2018.

[quote]Indians are least likely to break out of the income and educational bracket of their parents.[/quote]Much of this wealth is less likely to be distributed anytime soon, Indians are least likely to break out of the income and educational bracket of their parents than the citizens of five other large developing countries–Brazil, China, Egypt, Indonesia and Nigeria–IndiaSpend reported in June 2018, citing a World Bank report.

Lesser wealth results in lower life expectancy, poorer health outcomes and poor education outcomes, various studies showed. This adds to the fact that health emergencies often push people into poverty–55 million Indians in 2011-12.

Why it is becoming increasingly important to invest in people

These factors show that investments in social spending is a necessity. “Investing in people rather than primarily in infrastructure is the best way to achieve sustainable development, and investments in human capital through health and education offer compelling returns,” World Health Organization director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement.

Related article: Put people first, development will follow

Women’s well-being, estimated from their body mass index (BMI), education, early marriage and access to antenatal care (ANC), could explain half of the difference between high and low stunting rates in India, a 2018 study by the International Food Policy Research Institute showed, as IndiaSpend reported in July 2018.

Women’s BMI (19%) mattered more than even children’s adequate diet (9%) when it came to likelihood of stunting in children, the study found. Women’s health and empowerment have shown to directly influence child health and nutrition in many previous studies (here and here) as well.

Ensuring good health and more opportunities for economic growth for girls is certain to result in not only increased productivity and economic returns but also a more healthy future population.

Cash transfers have been used to reduce poverty in Latin America, Africa and Asia and these have delivered faster results than expected from the “trickle-down” effects of economic policies, said a 2017 International Labour Organization working paper.

“Although in practice benefits have tended to be lower than needed, a cash transfer at an adequate level can bring people out of poverty overnight,” the paper said.

Cash transfer helped reduce inequality in Brazil by 28% by GINI index–a measure of inequality–between 1995 and 2004 and child stunting halved from 13.6% to 7% in 2006.

A universal basic income (UBI)–a periodic, recurring, unconditional cash payment–was discussed at length in 2016-17 Economic Survey of India. UBI could help reduce leakages from current welfare systems and improve the quality of life of the poor, the report had said as IndiaSpend reported in June 2017.

“If 75% of the population received Rs 6,450 per capita per year, the UBI would cost India 4.2% of its gross domestic product,” we reported. However the government had said it may not be politically or economically feasible.

India’s public health expenditure is among the lowest in the world at 1.02% of GDP (2015), far behind the 5% recommended by experts and other low-income countries that average 1.4%. India has committed to spending upto 5% of its GDP on health by 2025 according to its National Health Policy.

Investing more and strengthening its public–especially primary–healthcare system is the way to improve accessibility and affordability of healthcare. While India has rolled out its ambitious Ayushman Bharat Yojana (National Health Protection Scheme) to insure 100 million Indian families and provide a cover of upto Rs 500,000, previous experience has shown that insurance model does not prevent impoverishment as it does not cover outpatient cost or medicines cost which are the two big healthcare expenses.

“We need a [healthcare] system that actually provides financial protection, appropriate care and universal access. The insurance programmes are well intentioned, but they do not fulfill these objectives,” said Srinath Reddy, director of Public Health Foundation of India, a think tank, to IndiaSpend in January 2018.

Universal health coverage, combining primary, secondary and tertiary services and creating a single payer system through pooling of multiple healthcare-funding resources and creating a large risk pool is one way to provide a truly universal coverage, Reddy said.

Correction: The story has been updated to show that $5 trillion is Rs 350 lakh crore, and not Rs 35 lakh crore as we said earlier. We regret the error.

The story was originally published on IndiaSpend, a data-driven, public-interest journalism non-profit.