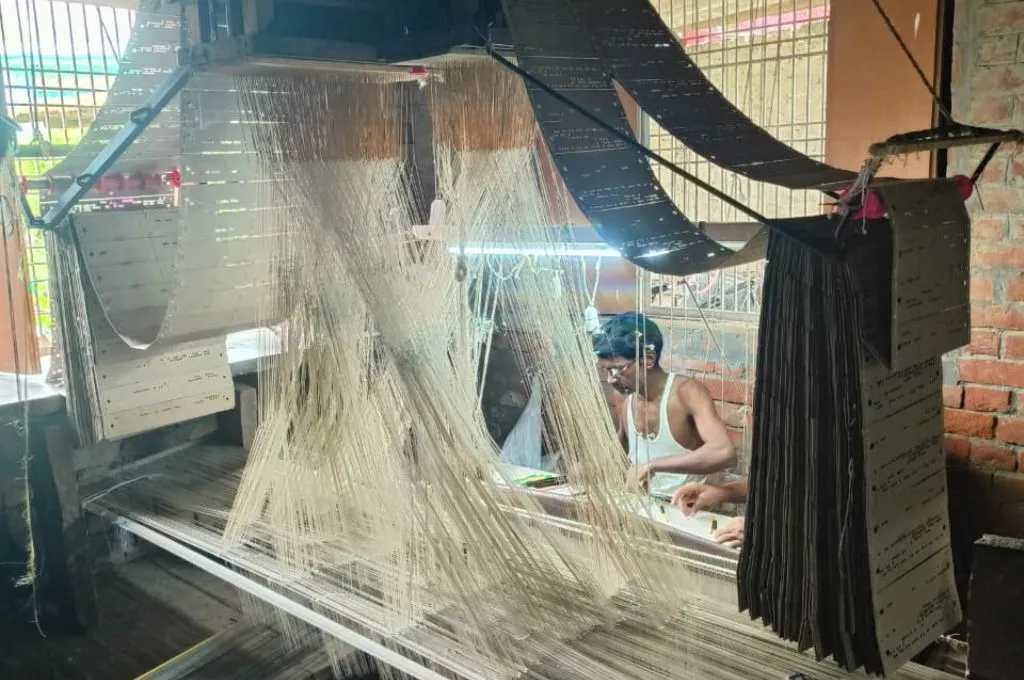

Is this the last generation of the Negamam saree weavers?

“They told us our lives would change after the geographical indication tag. But look around, what has changed for us?” asks Nagaraj, a third-generation handloom weaver from Negamam town in Tamil Nadu’s Coimbatore district. For more than 30 years, Nagaraj has woven Negamam cotton sarees, and his family members are also engaged in this work now.

Handloom weaving has thrived for over two centuries in the Pollachi, Negamam, Kinathukadavu, and Sulur regions of Coimbatore district. Three decades ago, the region had more than 4,650 handloom units. Today, as younger generations move away in search of stable livelihoods, this number has dropped to approximately 1,700.

In March 2023, Negamam Cotton Handloom Sarees received a geographical indication (GI) tag, a legal recognition meant to protect products whose quality and reputation are tied to a specific place. At the time, it was expected that the GI tag would garner higher demand, better wages, and recognition. But nearly two years later, Nagaraj says, “Our income is the same, our struggle is the same.”

It takes Nagaraj two full days to weave one Negamam cotton saree. He works from 7 am till evening, breaking only for lunch. However, he only earns INR 1,000–1,250 per saree. His family survives on a monthly income of INR 12,000–15,000 from weaving.

Government and cooperative orders are irregular, and payments are often delayed. “Some months there are only seven or nine sarees to weave,” Nagaraj adds. “I now depend on private textile shops. They may pay slightly less sometimes, but at least they pay on time.”

Deepanandhini, another weaver in the region, has woven Negamam cotton sarees for nearly 20 years, continuing a craft passed down through three generations of her family. “For us, weaving is not a profession. It is the life we were born into,” she says. “But even after giving our whole lives to this craft, we remain in poverty.”

Together with her husband, she earns approximately INR 1,100 per saree, which takes two days of joint labour. “Everyone in the chain makes money except us,” she says. The same saree sells in the market for INR 2,500–4,000.

“I have worn a Negamam cotton saree only once—at my daughter’s wedding,” she adds. “Even then, we bought the cheapest one. We weave these sarees every day, but cannot afford to wear our own work.”

While the weavers had pinned their hopes on the GI tag, a senior government official familiar with the GI registry process in Chennai, says, “A GI tag certifies origin. It does not automatically raise wages or create markets. Without branding, buyer linkages, and sustained state support, GI remains symbolic.”

The weavers no longer want their children to take up the same profession. Deepanandhini says, “We send our children to school because we don’t want them stuck at the loom like us. Almost all weavers’ children here have moved to other fields.”

“If things don’t change,” she adds, “we might be the last generation of Negamam weavers.”

This is an edited version of an article originally published on 101 Reporters.

Prasanth is a multimedia journalist based in Tamil Nadu.

—

Know more: Learn why Eri silk weavers are using solar power.