Four years ago, when Saajha started its interventions to enable parent participation in Delhi’s government schools, there were some clear indicators of parents’ poor awareness about their local schools: approximately 78 percent of the parents did not know the name of their ward’s class teacher and more than 90 percent of them were unaware of the school principal’s name. This is pretty much the case in most government schools, even today.

A large part of the problem can be traced to teachers often viewing parents as unwilling to participate in learning: “Yeh parents toh sirf paise lene aate hain” (Parents only come to school to take subsidies) and “Bacchon ko saaf kar ke bhi nahin bhejte” (They do not even send kids in properly groomed).

This lack of trust is often reflected in their behaviour towards parents, sabotaging the latter’s self-efficacy, which is often already compromised due to socio-economic and cultural factors.

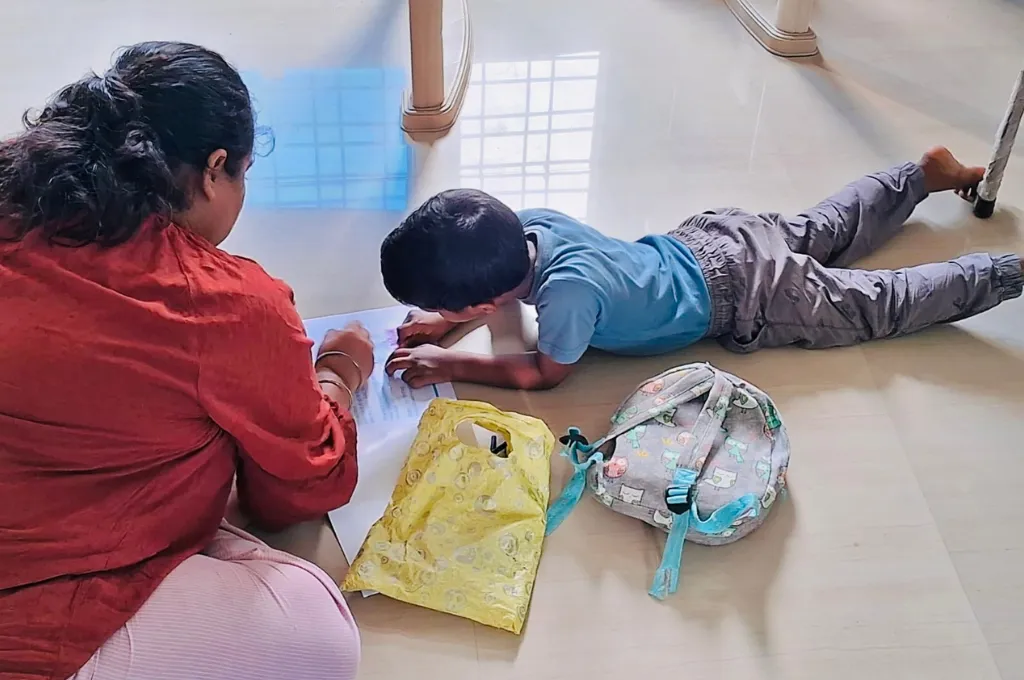

Parent participation can contribute to teaching-learning practices, improved school management, and systemic reform. (Photo Courtesy: Saajha)

Recognising the role of parents

The average number of school days in India is only around 150. Even with full attendance, children thus spend most of their active hours at home and in the community. It is therefore obvious that we need to redefine the role of parents from one that ends at the school gate to something more substantive.

There is enough evidence to show the significant role that parents play in their children’s education: PISA 2012 reports that regardless of the socio-economic background of households, parents ‘can help children achieve their full potential by spending some time talking and reading with them.’ A report by Young Lives, published in February this year, states that children ‘whose caregivers aspired for them to complete secondary education or above are three times more likely to continue schooling at age 19 than their counterparts.’

[quote]Most programmes implemented across the subcontinent miss acknowledging the role of parents.[/quote]

Most programmes implemented across the subcontinent however, miss acknowledging the role of parents; many of them are limited to mere awareness campaigns and ‘engagement’ events. Parent participation, in its truest sense however, has the potential to contribute to teaching-learning practices, improving school management, and enabling systemic reform.

For instance, an internal assessment of Saajha’s joint parent-teacher reading assessments revealed a 15 percent increase in the number of children who were able to read Grade-2 level texts. Armed with this data, members of the School Management Committee (SMC) decided to support teachers by arranging for local volunteers to help improve the reading levels of students. While authorised school inspectors tend to be more concerned about, say, the neatness of the official register, records, files, and so on, parent ambassadors participating in the SMC focused on improving the reading levels of their children.

Reimagining the role of parents

In today’s environment, children and parents are usually treated as customers; and just as customers are at the centre of innovation and design in the world of business, parents must also be treated as key participants in the quest for quality education.

In Delhi, where parents and community representatives were included in the design groups of several state-level programmes like summer camps, Mission Buniyaad and more, the results have been heartening. When SMC members were nominated to the zonal admission committees, there was a 10 percent increase in school admissions. Participating parents generated a demand for quality education by influencing the community from within, through active role modelling and door-to-door visits.

On the supply side, it is important to create a space for parents within the school and learning process. Parents have demonstrated different ways of participating in their children’s education. These include influencing decisions at the school level, creating learning spaces in their communities, and creating a learning environment in their homes.

After working with thousands of parents and witnessing a range of parent-participation approaches, we have defined parental participation across four circles: home, class, school and community. This encourages greater partnership based on need, interest, expertise and availability.

Parental participation is challenging in a country with large numbers of children as first-generation learners. (Photo Courtesy: Saajha)

Reforming the system to listen to parents

Sample data of 1,100 nominees to the SMC 2017 election in schools run by the Delhi Directorate of Education revealed that almost 80 percent of the parent nominees believed that much could change through their active participation in school management. The challenge, however, lies in sustaining their belief and optimism when the system takes an inordinate amount of time to address their grievances or demands.

A time-estimation study conducted by the Genpact Social Impact Fellows shows that initiating construction to meet the demand for a good classroom could take 391 days; problems with sewage and minor infrastructural repairs could take between 41 to 150 days for resolution; and that it could take months for a child to be able to read a book fluently.

[quote]Listening to what parents say—and taking timely action—is critical to ensuring continued participation of parents.[/quote]

Listening to what parents say—and taking timely action—therefore becomes a crucial factor for school and governments systems to ensure continued participation of parents. The SMC sabhas, where parents and decision makers from around 48 concerned departments have a dialogue, is one such platform. Up to 30 percent of school-related grievances are solved within 30 days because of these sabhas. Thus, a mechanism to connect parents to parents, parents to teachers and parents to the system must be a part of the change.

No doubt, parental participation in education is challenging in a country with large numbers of children as first-generation learners, wide social disparity and multiple cultural barriers to education. Parents consider schools as a trusted stranger and leave their children with that stranger. It is high time that this act is rewarded by recognising, reimagining and reforming their role by making them equal partners in the task of improving learning and academic outcomes for their children.