On 3 January, 2019, parliament amended Section 16 of the Right to Education (RTE) Act, popularly known as the ‘No Detention Policy’ (NDP). The policy guaranteed promotion through class 1-8 for all children, irrespective of their readiness. The now amended policy allows states to frame rules that could re-introduce detention in class 5 or class 8.

The rationale provided for the amendment is as follows: with guaranteed promotion, students and teachers feel no compulsion to learn or teach, which has an adverse impact on learning. The sub-text being — high stakes exams help drive learning.

This notion was tackled by the original framers of RTE, who argued that exams create unnecessary pressure, and detention as a consequence of exams, is unhealthy for children. Holding children back in classrooms where they have failed to learn, without changing anything about the teaching-learning process, doesn’t improve learning. It leads to children dropping out. Additionally, detention in early classes labels children as ‘failures’ too soon; and for that reason alone, detention in elementary school should be prohibited.

Holding children back in classrooms where they have failed to learn, without changing anything about the teaching-learning process, doesn’t improve learning.

It should be noted that RTE did not introduce the idea of no-detention in all states. Pre-RTE, several states already had automatic promotion till class 5 or 8. While states like Haryana, Kerala, and Uttar Pradesh allowed student detention as early as class 2, 14 out of 28 states1 detained children only in class 5 or above. If NDP was responsible for declining student outcomes, then this decline should have been observed pre-RTE as well, and not just post. However, this trend is not borne out in data.

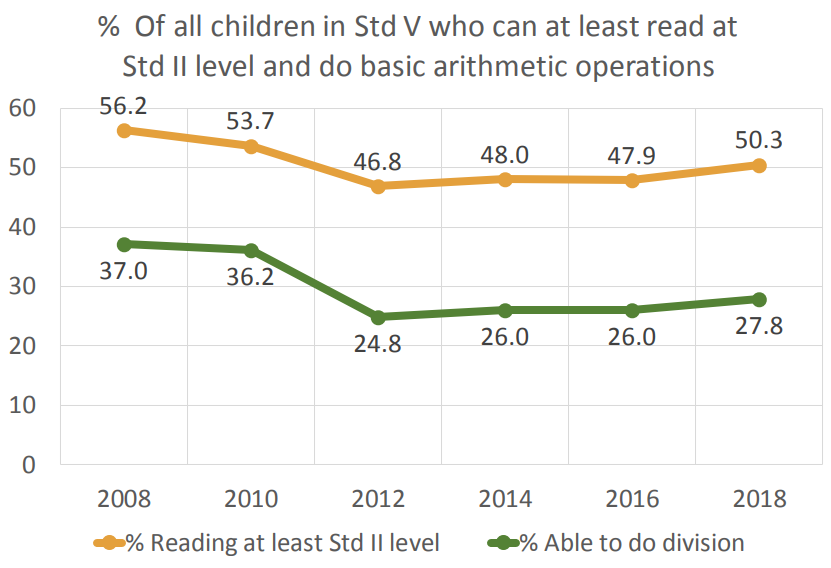

National Achievement Survey (NAS)2 data shows that between 2003 and 2007, 19 out of 28 states with a no-detention policy showed improvements in learning. In other words, states improved their results in 2007 without detaining students. Positive trends in reading were reported in the early ASER surveys of 2005-2007 as well. Curiously, learning outcomes dipped soon after. ASER series data (presented below) captured a falling trend in learning, and the ASER 2012 report noted a correlation between the passing of RTE, and slide in learning levels.

One could say this negative trend strengthens the claim that NDP led to a decline in outcomes. However, with NDP still intact, results showed an uptick in many states between ASER 2016-18. It is clear that something besides detention or promotion swings learning in classrooms – that something which improved outcomes between 2003-2007, depressed them between 2010-2014, and pushed them to recover slightly thereafter – no-detention being the norm all the while.

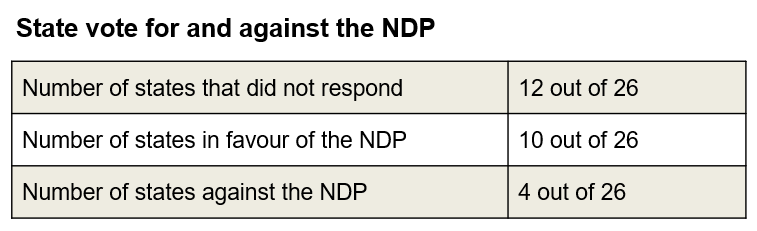

The main point here is not whether a no-detention policy helps children, or hurts them. The point is to showcase – with NDP as an example – the troubled state of education policy making in India. In the absence of good, reliable data, education administrators, or policy makers design policies based on anecdote, or pressure from important stakeholders, while key stakeholders get ignored. For instance, in the case of NDP, all states were invited to vote in favour or against the policy. A majority voted to continue NDP.

States were also asked to survey teachers, parents, and academic faculty on the merits and demerits of NDP. Mostly all said that students should not be detained as it demoralises them. Teachers and parents also emphasised that exams induce fear and stress. Instead, support for better teaching and evaluation methods was requested. For some reason, none of this swung the decision in favour of NDP, and parliament decided to dilute a policy that enjoyed the support of many.

Teachers and parents emphasised that exams induce fear and stress. Instead, support for better teaching and evaluation methods was requested.

NDP is not the only casualty of opaque policy making. The education sector is rife with decisions taken on the basis of everything except evidence. Inter-dependencies are ignored, with one aspect of schooling being tweaked, without consideration of how that impacts other areas. In this context, while there are real challenges in procuring reliable data, disregarding data when it does exist, further entrenches arbitrary decision making.

One silver lining in NDP amendment is that states have been given a choice on whether to detain students, or continue with a no-detention policy. The hope is states will examine evidence, confront the real issues plaguing education, and do what is right by children.

- States excluded – Sikkim, J&K, and Telangana

- A periodic, nation-wide, learning outcomes assessment conducted by the National Council for Educational Research and Training (NCERT)

Disclaimer: IDR is funded by Rohini Nilekani Philanthropies.