Entertainment in the form of film, theatre, and television has, since time immemorial, influenced the ways in which humans think and society behaves. Often, this happens inadvertently and depends significantly on the creator’s experience, personal story, intention, and ability to tell a good story with an effective message.

So, if you’re an organisation or individual who wants to tell stories with significance, and create impact through entertainment, what’s the best way to do it? How do you convey a message without preaching to the audience? How do you maintain an entertaining tone without diluting the issue?

There are several challenges to doing this, but to help answer the question of ‘how’, we analysed eight films that we thought successfully brought entertainment and impact together. These were Anaarkali of Aarah, Newton, Padman, Pink, Rang de Basanti, Shahid, The Avengers, and The Big Short.

We defined impact at three levels—individual, societal, and institutional:

Individual: Driving individual engagement through an increase in awareness, information, or interest in the issue, leading to a mindset shift or an inclination to take action.

Societal: Collective action which might take the form of conversations, petitions, protests, or other means of mobilising communities by combining resources and energy.

Institutional: The audience is made familiar with, and given an understanding of how public institutions such as the judiciary, legislative, or executive function; they are also told about ways of engaging with these institutions to drive reform.

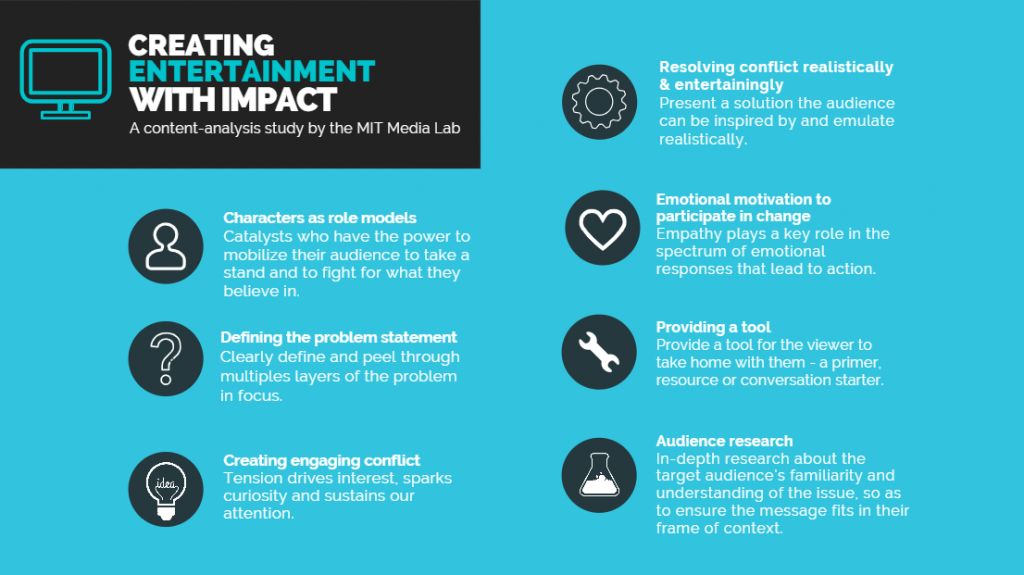

Using the above definitions of impact, we used ten metrics to develop a guide that lists the seven practices you need, to create high-impact media. The metrics included entertainment value, significance of issue, communication of issue, civic value: individual, societal, and constitutional, communication of civic values, audience empowerment, evidence of real-world impact, and commercial success.

The seven best practices

One of the most powerful ways to create impact through entertainment is by developing characters as role models for the audience. Miguel Sabido, a Mexican TV producer and a pioneer of entertainment-education, explains the need for three character role models:

- Positive models—they embody the intended message or behaviour, and are often presented as passionate, charismatic, solutions-driven, optimistic enablers whom we would like to become more like.

- Negative models—they display the incorrect action, and signal an undesirable way of thinking or behaving.

- Transitional models—they move from the negative to positive, actively modelling to the audience ways to evolve thought and behaviour from confusion or disinterest, to awareness and action.

How do you maintain an entertaining tone without diluting the issue?

Imitation usually comes from the third kind (transitional) since the viewer is able to relate to their thought process and their transition from confusion or disinterest, to awareness and action. Engagement is driven by inspirational characters who function as role models. They act as catalysts who have the power to mobilise their audience and fight for what they believe in.

For example, the Bollywood film Rang De Basanti shows a group of students who are generally disinterested in politics until a corruption scandal at the Ministry of Defence takes the life of a close friend. The first part of the film establishes the group’s relatability to young Indian audiences via scenes of their college life and dialogues about the sad state of politics in the country. The second part provides inspiration to take action for any ordinary citizen who has ever complained about the ‘corrupt system’.

This was evident in the real life activism that the movie triggered, from inspiring Delhi University students to spearheading a campaign for the retrial of the Priyadarshini Mattoo case (where actors from Rang De Basanti were present), to the candlelight vigil (held at India Gate just as the movie had depicted) that led to the opening of the Jessica Lal murder case and the subsequent imprisonment of Manu Sharma.

Related article: When real life mimics ‘reel’ life

The content must clearly define and peel through the many layers of the problem in focus. Doing so establishes in the audience’s mind that this is not just a passing conflict in the film, but a significant social problem.

The content must clearly define and peel through the many layers of the problem in focus.

The content should also identify one or two critical root causes of the problem, rather than make assumptions about the audience’s understanding of it. This is often best done by focusing on an aspect of an issue that is part of public conversation—for instance, menstrual hygiene—while presenting a fresh dimension to its origin. In the movie, Padman, there is a clear scene where the hero Akshay Kumar (the transitional character of the movie) is in a doctor’s clinic. The doctor clearly explains to him the dangers of women using old napkins, leaves, or other unhygienic material in place of sanitary napkins. In this scene, Kumar is unaware of the problem himself, and through his education, the audience too is made aware as to why sanitary napkins are essential.

It is absolutely critical to understand the audience and their ability to be affected by the issue presented | Picture courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Tension in a story drives interest, sparks curiosity, and sustains our attention. Media with a cause often focuses on defining the social problem and assumes that the audience sees it as an engaging conflict to be invested in. However, this is insufficient. For the conflict to create some sort of tension, the audience needs to find a personal connection to it. If they are not yet aware, invested, or connected with the problem, then this conflict has little value for them.

And so the conflict must often be presented in the form of relationships between characters, impending drama, or a fearful consequence. In most cases, the audience is propelled to root for a team or for a certain desired outcome; this makes them personally invested and engaged till the very end. For example, in Anaarkali of Aarah, a movie about a small-town folk dancer in India, the dancer is molested by the vice chancellor of a local university during a performance. The conflict is not the incident itself, but the dancer’s fight for justice against a powerful man highlights her right for consent irrespective of her background.

Conflict resolution is important when presenting a solution to a problem. This is where the most delicate balance between entertainment and education is struck. Presenting a resolution that is extraordinary and high in emotion can be tempting, but often falls short of offering a realistic solution to the audience.

If the resolution requires random or divine intervention, it will have little or no impact. It must inspire the audience and be realistically replicable, while also having sufficient emotional quotient to keep people engaged.

In Pink, a court-room drama about sexual harassment and consent, the conflict resolution happens through a powerful speech by leading actor, Amitabh Bachchan. It charges the audience while making a successful legal argument around consent. In contrast, Rang De Basanti fares less well, as the film’s ending is overly emotional with the students turning vigilante and murdering the corrupt politician. This is perceived as both an unrealistic end as well as an undesirable solution for the problem at hand.

Nearly all the successful case-studies we analysed elicit a strong emotional response to the cause, ranging from anger and frustration, to shame and hope. However, what’s important is that the content is able to shift its audience from viewing to doing.

Different emotions lead to different reactions. The ending of Shahid, a movie about the Indian activist-lawyer Shahid Azmi, could anger you and leave you despondent about the state of affairs, or it could inspire you to act; Padman on the other hand makes you aware about the problem and motivates you to do something about it. Understanding what emotion will lead to what desired outcome is important for creating impact. Psychological and neuroscientific research show that empathy sparks neural processes that lead to both ‘experience sharing’ and ‘perspective taking’ that fuel action to rectify the problems that impact the people we’re empathising with.

Seven best practices for creating entertainment with impact | Picture courtesy: MIT Media Lab

Moving the audience from inspiration to action requires giving them tools for the real world. A tool can range from a well-structured primer on the social issue, to a resource they can share with others. It should give the audience a pathway to drive the kind of change that the content helps them envision.

Moving the audience from inspiration to action requires giving them tools for the real world.

In Pink, Bachchan explains consent in a language lay-people can understand. His monologue becomes a tool for the audience to get a clear and simplified understanding of the legal context around consent, and to then use this to either spark a conversation or to challenge an opposing view. In Newton, a movie about running elections in a conflict-ridden part of India, the tool is presented as a guidebook for those working in the public administration or interested in understanding the electoral process.

Related article: The case for adaptive programming

Finally, it is absolutely critical to understand the audience and their ability to be affected by the issue presented. This requires three pieces of audience-focused research.

First, the research needs to explore the audience composition: their habits, lifestyles, concerns, interests, and fears. These ‘personas’ will help inform how the message, format, and characters should be crafted in order to be relatable. This is especially true for developing the positive, negative, and transitional characters.

Second, the content creators must understand the audience’s prior interest and knowledge of the issue in question. For example, if the audience has little awareness of the issue, then skipping a step and offering a solution directly, may not work. The content must be based on identifying where along the spectrum of awareness to solution-taking, the audience lies.

Third, in order for the audience to take any action, the content needs to be created keeping in mind the resources it has—motivation, time, financial or social capital, or political clout.