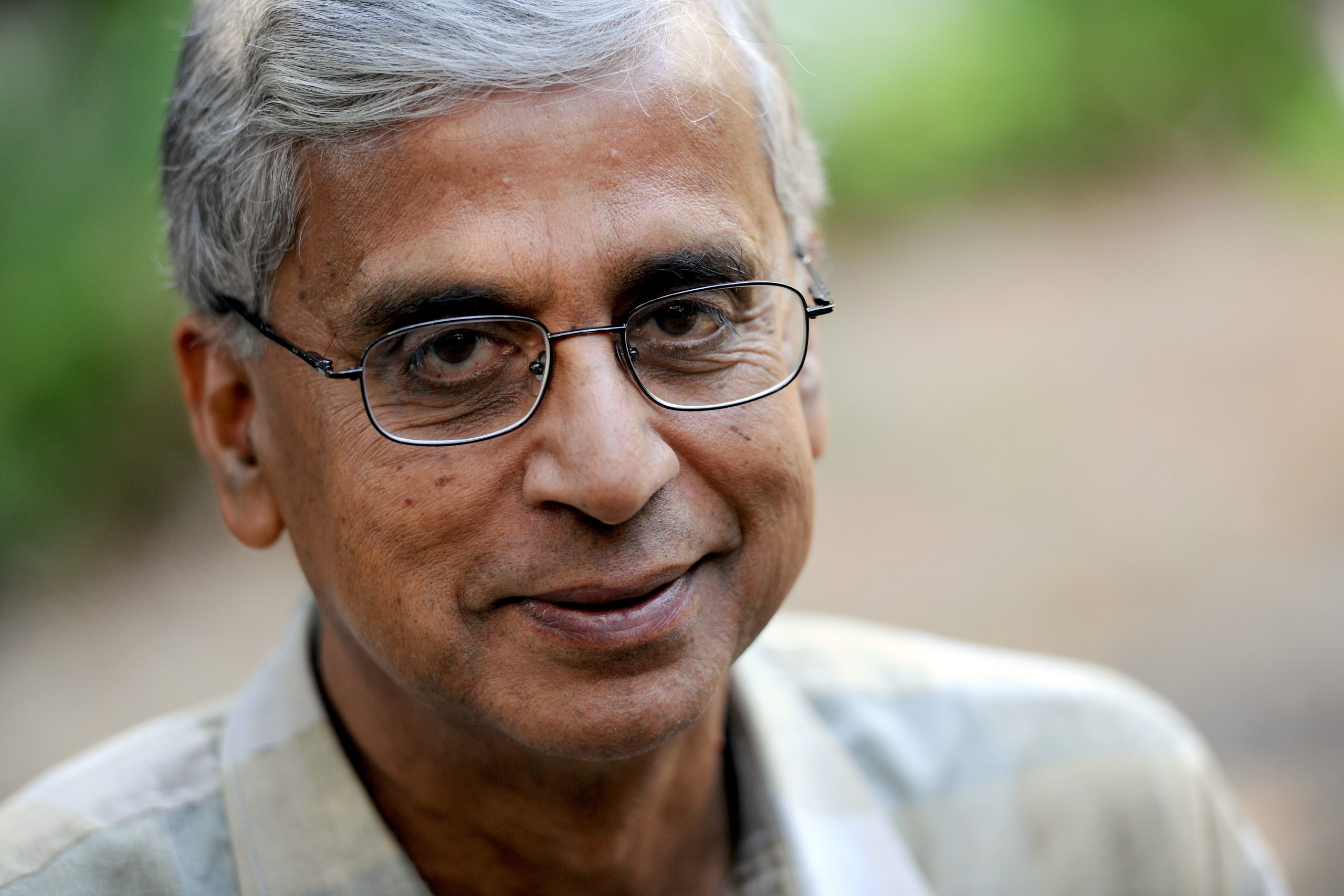

Founder of Karuna Trust and VGKK, Padma Shri Dr H Sudarshan has been at the forefront of reforming the health system in Karnataka. While the initial decades of his working life were dedicated to working with tribal communities, Dr Sudarshan has since worked across health, education, and livelihoods in several states across India. As the founder-trustee of the Suvarna Aarogya Swasthya Trust (SAST), he has several years of hands-on experience in designing and providing universal health coverage to the people of Karnataka.

Picture courtesy: The Right Livelihood Foundation

You’ve been a big proponent of health assurance versus insurance. Could you tell us a bit more?

In a country like India, where a bulk of our population is below the poverty line, we need health assurance, and not health insurance.

Health assurance means that the government or a quasi-government body will manage the health coverage process (manage the funds, empanel the doctors, and settle the claims) so that all citizens are covered under the scheme.

Health assurance means all citizens are covered under the scheme.

This model of health assurance or what we call Universal Health Coverage (UHC) has been tried in Karnataka—starting with the Vajpayee Arogyashree scheme—and has been successful with almost 6.5 crore people in the state who are now covered under it. The scheme was set up to bridge the gap in provision of tertiary care, particularly in rural areas. Suvarna Arogya Suraksha Trust (SAST) was set up to run it, and it was rolled out in a phased manner.

Related article: Healthcare is an essential human right, and so is a proper diagnosis

When we set up SAST we incorporated lessons from the failings of the Rajiv Arogyashree—which was first implemented in Andhra Pradesh in 2008. And I think our experience in Karnataka has learnings for other states as they implement Ayushman Bharat, which draws heavily from SAST, and Aarogyasri—run by the government of Andhra Pradesh (AP), which enabled BPL families to obtain healthcare services at government and private hospitals free of cost.

Given your experience in running SAST, what are some of the things that state governments should be paying attention to, as they seek to operationalise Ayushman Bharat?

There are few key learnings that are important if we want to make Ayushman Bharat achieve what it’s supposed to do, which is provide universal health coverage for all.

In the initial days, the Aarogyasri scheme covered more than 1,200 procedures, including expensive ones like cochlear ear transplants that cost INR six to eight lakh per operation.

The number of procedures and the cost of covering them was very high, making it unviable for the AP government. The annual budget for managing this scheme was more than INR 1,000 crore and it had to be borne entirely by the state government.

Photo courtesy: Charlotte Anderson

Learning from this, we reduced the number of procedures to 450 ‘most essential’ ones in the state of Karnataka. We started with a budget of about INR 200 crores, which was affordable for the state. Over a period of time this budget increased to INR 600 crores. This year we have a total budget of INR 1,000 crores. If Ayushman Bharat is operationalised, a big share will come from the central government.

Fraud can happen both at hospitals as well as at insurance companies. I had first-hand insight into the kinds of frauds that could be perpetrated when I was the vigilance director at Lokayukta in Karnataka from 2002-2005. Some of these included fraudulent claims, kickbacks in the claim settlement process, hospitals charging patients despite them having insurance plans, and so on.

Related article: The trouble with developing a framework for primary healthcare delivery

We need good fraud control.

To reduce fraud at the hospital level, at SAST all claims were settled via electronic transfer of money directly to the hospitals; there were no kickbacks or commissions.

SAST, and now Ayushman Bharat, are supposed to be completely cashless schemes—patients are not required to pay anything if they are covered. However some hospitals still make some patients pay despite the fact that they are not allowed to charge the patient at all. To prevent it from happening we need good fraud control against such practices.

In the case of states that have the RSBY programme through insurance companies, the premium is paid by the state government. The insurance companies are supposed to be selected through a tendering process that ensures that the state government gets the best deal for their people. However, given how powerful these companies are, there is likely to be corruption and fraud during both the selection as well as administration process.

We noticed that a few private hospitals and several government hospitals were not sending the claims of the patients covered under the scheme in time. At SAST, we penalised hospitals, and fined them if they didn’t put in their claims on time. This also served as an indicator to everyone that payment of claims on time was important to us; as a result, hospitals and patients were happy and spread the word, thereby ensuring more and more people availed of this benefit.

When SAST started the programme to cover BPL population, we ensured that they could just use their BPL card rather than having a separate card just for insurance. This worked well as the most vulnerable and marginalised, including scheduled castes and tribes, started availing of the service, and we’ve seen utilisation among these groups grow with time. In Karnataka, 60 percent of the people are BPL.

The central government has stated that since many of the states may not have the existing know-how to run a trust like SAST, they should necessarily work with the insurance companies. I, however, am not in favour of involving insurance companies in a UHC scheme.

Most state governments are not empowered enough to negotiate fair terms from insurance companies; there is an imbalance between the clout and influence that insurance companies wield versus what the state governments are able to extract from them in terms of affordable premium rates and claims mechanisms.

Working with quasi-government entities is much better than dealing with insurance companies, which focus entirely on revenues and profits.

I truly believe that working with quasi-government entities is much better than dealing with insurance companies, which focus entirely on revenues and profits. Hence, I would urge the states to focus on developing independent trusts like the SAST, whose mandate is to ensure universal coverage, instead of giving their budgets to insurance companies to manage the Ayushman Bharat scheme, even if it means that the process of doing so delays the launch of the programme by six to twelve months.

If setting up these trusts is not an option, then the capacity of state officials must be built so that they are knowledgeable about how insurance works, and can negotiate good terms and conditions. This would help ensure that the insurance companies don’t end up swindling money.

Another issue with insurance companies is their reluctance to settle claims of the healthcare provider (hospitals). They make money when the claims ratio goes down; it is therefore important to keep watch over how much they ‘save’. If they save too much money, then governments should have clauses to reduce the premium rates.

Where is Karnataka now with respect to UHC?

I’m proud to say that SAST has now almost reached universal coverage. Almost all of Karnataka—a total of 6.5 crore people—will be covered under the SAST scheme. Everyone except perhaps those professionals with access to private insurance offered by their employers.

So, what began as a small community health insurance initiative of Karuna Trust, 14 years ago enabled us to develop the SAST programme for the state government. and has now become the blueprint for an all-India programme, albeit not quite like we had envisaged.

State level universal health coverage schemes can offer Ayushman Bharat—scheduled to launch this September—valuable lessons.