As the renewable energy (RE) industry doubles down on deployment, it is imperative that stakeholders adopt a responsible approach to how we produce, deploy, consume, and value RE, one that is ecologically positive and people-centric.

While the sector increasingly recognises the importance of responsibility, it often lacks a clear, shared framework to guide how to implement it in practice. Without standard benchmarks and protocols, efforts remain fragmented, limiting the potential for a responsible RE transition.

It is to address this lacuna that the Responsible Energy Initiative (REI), of which the Council on Energy, Environment and Water (CEEW) is a part, has developed a framework for responsible RE deployment, titled ‘How Can India Enable a People-centric Clean Energy Transition?’

In this interview, Akanksha Tyagi, Programme Lead at CEEW and one of the framework’s chief authors, speaks with Joeanna Rebello Fernandes about its key features and how both new and ongoing RE projects can put its principles into practice.

Where does India’s RE sector stand on the spectrum of responsible deployment?

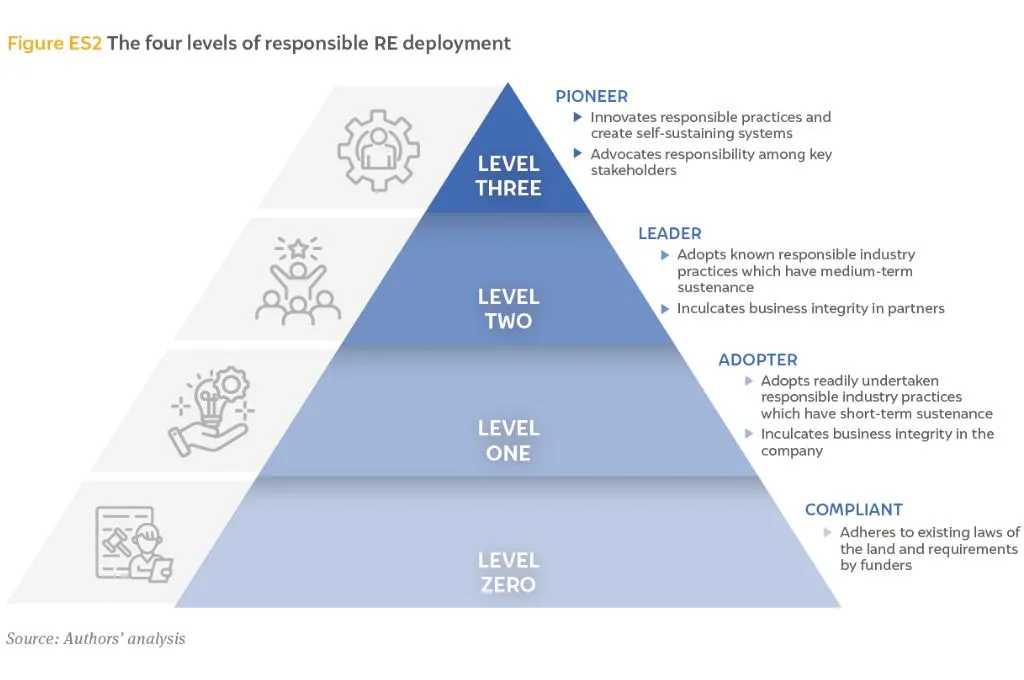

There’s no straightforward answer to this question. Based on our consultations with RE companies, communities, and policymakers for the responsible RE framework, the majority of the Indian developer ecosystem is at the ‘complier’ level, which our framework describes as level zero. This means that most developers simply follow the laws they are required to follow. And some may additionally adopt the guidelines prescribed by their financers. But there are no intentional efforts towards a responsible approach.

Having said that, a few developers are early adopters of responsible practices and have developed their own checklists to mitigate social and environmental impacts. For example, they may choose not to site their projects in places where the local ecology may be negatively impacted. Or they may insist that their organisation and the external actors they hire or contract adhere to a strong value system. However, the majority of the Indian RE industry stops short at compliance.

What does responsible deployment of an RE project entail for different stakeholders in the system?

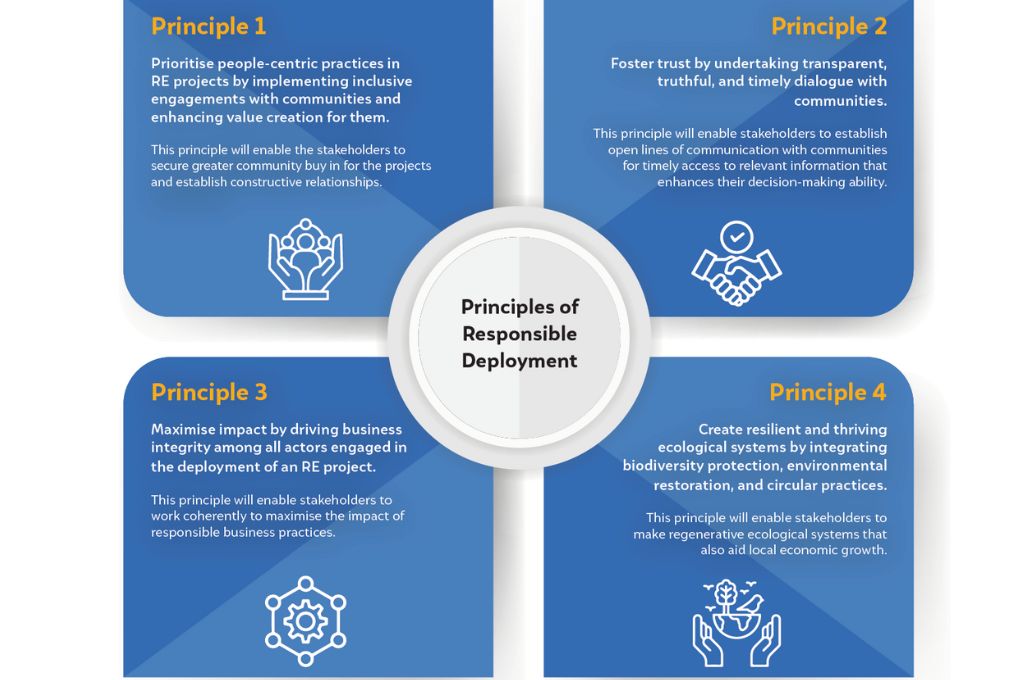

Responsible deployment would mean that an RE project has been conceptualised and implemented in a people-centric manner—from its siting to design, execution, and operation. Such projects enhance community value throughout the deployment process. They ensure that all communication between the private sector and local communities is transparent, and that deployment processes prioritise ecological sustainability, with the potential to create a regenerative future for the communities and the environment.

The first circle of stakeholders in such a system comprises the project developers who create the infrastructure, and the communities that live around the project and stand to be impacted by it. The second circle includes the government, investors, and buyers of electricity. Also within this circle are the business partners of project developers—such as engineering, construction, and procurement (EPC) firms and land aggregators—who are crucial for project execution.

To deploy an RE project responsibly, all these actors need to be on the same page regarding responsible practices and the level of ambition benchmarked for them. For example, a developer may insist on following just the guidelines laid out by their investor. To them, that level of compliance indicates responsible practice. However, for local communities who feel that they were not involved at key stages of the project or that necessary information was withheld from them, the project was not responsibly deployed because the conversations leading up to it were neither transparent nor timely.

Any large infrastructure project typically requires an Environmental and Sustainability Impact Assessment (ESIA). But in India, RE projects are classified as white industries—essentially those that do not degrade the environment—so they are not obliged to conduct ESIA studies. Yet several investors insist on them. Therefore, the only compliance that RE developers work towards is investor-driven. But developers who do not raise funds from such an investor are not expected to conduct these assessments.

Developers need to know how much capacity needs to be built institutionally.

So, the level of ambition and expectation is often different for different stakeholders. Therefore, it’s important that all stakeholders come to a common understanding of the definition and level of ambition for responsible RE, as well as a common appreciation for what’s at stake.

They need to understand, for instance, that responsible practices can still be resource-intensive—they need additional finance and human resources. Developers also need to know how much capacity needs to be built institutionally to deliver on a responsible RE project. [This includes,] for instance, training their project teams to follow a responsible RE framework, or funds for the additional work required before the project can be physically set up.

A clear detailing of these requirements gives stakeholders the agency to arrange for the necessary resources. [Then] when a developer approaches an investor, they can ask for a bigger finance pool, because they will want to undertake additional activities over and above the basic project costs to meet the yardsticks of responsible deployment. In the same vein, they could ask policymakers for more information—for instance, on land records, protected areas, or strategic infrastructure in the state—to prevent potential conflicts later. They could also engage with communities to understand their local area development needs and conduct other social baseline assessments that would inform their project activities.

Can you take us through some of the key features of the framework?

This framework is the first attempt in the RE sector to provide standard guidance for different stakeholders—the private sector, government, and communities. It is a common document to which they can refer to arrive at a shared understanding of what responsible deployment is, grasp its guiding principles, learn how to evaluate their current actions, and assess where they lie on the spectrum of responsibility. One of the key features of this framework is that once a project developer answers some of the basic questions in the document, it offers them detailed, actionable, and contextualised recommendations on how to initiate or scale responsible practices.

The framework lays out four principles.

The framework also categorises ambition (of responsible action) into four levels, based on the stakeholder’s ability to influence people in their networks and, at the same time, sustain responsible business practices. The goal is that the system should continue to operate and remain sustainable even without the stakeholder’s active participation or eventual exit from the project, and regardless of whether their interventions are short or long term.

These principles and levels of deployment can be adopted by all RE stakeholders. But we have contextualised them into a tangible set of recommendations for developers, as they are among the most important stakeholders in the sector and have the greatest agency to bring about change.

These recommendations include:

- Adopting low-impact siting practices for RE projects

- Evaluating and institutionalising funding requirements for implementing responsible practices

- Setting up an internal cell to operationalise the framework

- Building the capacity of on-ground and company actors to familiarise and understand responsible practices

- Assessing and re-establishing the selection criteria for subcontractors, such as land aggregators and EPC contractors

Our next step is to develop a guidebook that will make the framework more actionable for developers. The guidebook will expand on the principles and levels of ambitions drawn up in the framework. It will also cite examples from India and abroad to help developers better visualise how responsible RE deployment can be accomplished and what impact it has.

In parallel, we will conduct workshops to take people through the framework and the guidebook (when it’s launched) and assess what kind of support they’d need to adopt our recommendations. We have also planned to implement this guidebook with a stakeholder to assess its impact on the ground. This would involve identifying a couple of projects that are at different stages of deployment and implementing the relevant sections of the guidebook.

The framework is a voluntary document. What will incentivise developers to adopt it?

The document not only lays out responsible practices but also highlights the opportunities that they unlock by adopting them. For example, if developers have transparent and timely conversations with their communities, they can pre-empt and mitigate some of the potential land procurement challenges that arise later. This will help them appreciate the value of adopting a responsible approach and will steadily create a natural demand for the framework.

We started working on this document when we realised that several RE projects were running into delays, some of which were related to their social and environmental impacts. It was clear that these issues need to be dealt with systematically to ensure that India’s energy transition was uninterrupted. For a developer, the social license to operate hinges largely on the community’s perception of RE projects. If the developer undermines this, they risk delays and conflicts with local communities on land-related or environmental matters. They could even have run-ins with state authorities. This has been happening in India and globally. Communities are happy to support the clean energy transition as long as it’s happening elsewhere, which is part of the ‘not in my backyard (NIMBY)’ or ‘build absolutely nothing anywhere near anyone’ (BANANA) phenomena. Often, challenges like this arise when communities are not made an equal party to discussions when projects are being conceptualised.

The guidelines of this framework allow companies to self-assess their current actions and find out whether these actions are inclusive, people-centric, and transparent. Companies can accordingly realign their approach to become more inclusive by adhering to some of these values. Overall, the guidelines will allow them to enhance their social license to operate and deploy projects more seamlessly and in harmony with the surrounding ecology—that is, with people and the environment.

As the speed and scale of deployment increase, the intensity and frequency of conflicts are likely to increase too.

As we continue to deploy more and more renewables—because they are our biggest chance of fighting climate change—projects will inch closer and closer to communities, given the physical constraints of where this infrastructure can be sited. Developers may have to set up projects in densely populated areas, or in areas where there are already competing uses of land. Currently, RE installed capacity is relatively small, so the challenges don’t seem significant, although competing land use for agriculture and renewables has started to create conflict. And as the speed and scale of deployment increase, the intensity and frequency of conflicts are likely to increase too.

On the other hand, developers are also alert to the changing investor landscape. Globally, more investors are asking for companies’ environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosures. They are also assessing how past projects were deployed and evaluating their perceptions. Consequently, developers are now being nudged towards considering the impact parameters and assessments they should disclose to their investors to make them eligible for the finance required to deliver on responsible ambitions.

So, from the point of view of business as well as that of social license, companies will find merit in using this voluntary framework to self-assess and intentionally move towards higher levels of responsibility.

How will the framework benefit investors and policymakers?

The concept of responsible RE deployment is yet to be mainstreamed. As a result, for developers to adopt and demonstrate it, they would require additional finance. The framework will help investors internalise that their support is critical to providing this financial support and scaling responsible deployment practices. It will also urge them to revisit how they evaluate the profitability of projects, moving beyond the classic rules of risk assessments and returns.

Adopting a responsible approach may require developers to undertake some activities at an institutional level, such as building capacities of employees. This is a long-term investment, but one that will continue to yield returns as the developer goes on to deploy more projects. Now, an investor financing a single project will expect a certain level of returns. But when they acknowledge that the aggregate returns from the Indian RE industry will improve if all developers start deploying these practices, they’ll appreciate the long-term returns that the investor community stands to gain. But for investors to grasp the quantum of finance needed for responsible deployment, they’ll first need to understand how extensive responsible practices are.

The framework will also help investors reframe their evaluation metrics and set new benchmarks for financing responsible projects.

These choices will also signal policy changes that support responsibly deployed projects. Investors—particularly multilateral development banks—can work with governments to inform their policies.

As for policymakers, this document can help them improve project deployment guidelines at both the state and national levels—[such as] on how solar or wind parks should be set up responsibly. Making responsible practices mandatory will narrow the gap between what is ‘good to do’ and what a developer should do. This will eventually drive a more natural adoption of responsible RE practices and create a level playing field for all actors.

The development of the RE sector is well underway. How can existing projects best adapt to these guidelines?

The maximum potential of responsible deployment lies in early adoption, when the project is just getting started. But there’s also an opportunity for current projects to make their operations more resilient. For one, developers can create an open line of communication with communities, which will help build trust with them. Project teams on site can become more accessible to them, address their queries and concerns (such as the long-term impacts of an RE project on land), and find ways to incorporate some of their insights into CSR programmes.

Developers have an opportunity to act responsibly even when a project changes hands. They can do this by ensuring that the new actors who have taken over the project also have access to its history and all the relevant information about the surrounding communities and the local environmental landscape.

When developing this framework, what telling insights surfaced from your fieldwork?

Our fieldwork in Karnataka showed us that communities viewed RE projects as an opportunity to participate in the clean energy transition themselves. In Koppal and Chitradurga districts, which have a high penetration of RE projects, the level of local understanding about the energy transition was quite advanced. Communities said they did not simply want to give up their land but wanted to be equity holders in upcoming projects, so that they could have more control over the revenue and the incomes that the project generated. Communities were also keen to work with developers on ways to care for the local environment. They said they could do this by offering guidance on the project design or advising the developer on which access routes to leave alone, so as not to disrupt the community’s day-to-day operations. These conversations helped us realise that communities were thinking about the transition progressively and viewed RE as an opportunity to diversify their incomes, even as they sought to play a more meaningful role in it. They wanted greater harmony with the infrastructural assets coming up around them, and with the people operating those assets.

On the other hand, consultations with developers and investors revealed that several of them had proactively adopted responsible business practices. Cutting across the scale of operations, from small to large, each developer had their own checklist of responsible practices. Of course, the comprehensiveness of those checklists varied, and there was scope of improving them. But it was great to know that many of these companies have already taken the lead on responsible action. And when we asked them what prompted them to come up with these standards, they echoed the same gaps and opportunities that we had identified in our research, which validated the need for our framework and upcoming guidebook. These are not simply pieces of research but tangible, practical tools that will help solve the problems in the RE sector—problems that some players are already confronting and looking to solve.

—

Know more

- Learn how renewable energy models can put people first.

- Watch this video to learn about the impact of solar parks on the communities in Tamil Nadu.