The philanthropic sector as a whole has spent the better part of the past decade seeking to increase effectiveness through increased accountability, measuring impact, and heightened due diligence. However, recent research by Open Road Alliance, a private philanthropic initiative based in Washington DC, suggests that these efforts to professionalise our own work through increased policy and procedure have made funders the biggest barrier to effective impact. In other words, funders have become their own enemy in the pursuit of impact and ROI, and are the greatest pain point for nonprofits and social enterprises.

As such, every organisation that approaches ORA for funding is facing an impact-threatening problem.

Since 2012, Open Road Alliance has been providing capital to social impact organisations facing an unexpected roadblock during project implementation.

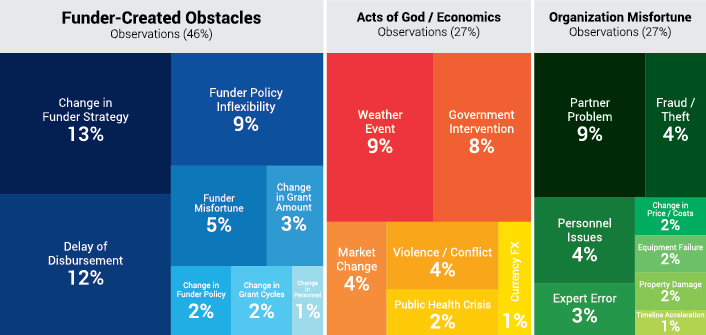

A 2017 roadblock analysis report by Open Road says that almost 46% of challenges or obstacles faced by organisations are either funder-related or funder-created. In total, ORA analysed 102 applications from the past five years to assess trends in its portfolio, looking at multiple variables, including the organisation’s size, project type, sector focus, geographic focus, legal status, and type of original funder. The findings from this multivariable roadblock analysis provide the first-ever empirical dataset on ‘what goes wrong’ in impact focused projects and offers early conclusions on how specific roadblocks correlate with other variables.

Methodology

Over the past five years, Open Road has systematically collected data on its portfolio of applicants for grants and loans, including applications that were ultimately denied. As of September 1, 2017, this dataset comprised 102 applications, which were analysed for trends, patterns, and any statistically significant correlations using descriptive analysis and statistical analysis via probit regressions in STATA.

Each data point in their set represents a project that was mid-implementation (i.e., fully funded) and that experienced an unforeseen disruption that required a one-time grant or loan to implement a solution. So, each of the 102 projects encountered an unexpected obstacle that, without additional funding, would have derailed impact.

Sub-Saharan Africa projects make up 52% of roadblock’s portfolio. Southeast Asia (including India) projects make up 7% of roadblock’s portfolio. The other regions’ percentages remain relatively consistent from the roadblock portfolio.

Findings

The biggest obstacles faced by nonprofits are created by none other than their own funders. In Asia, the Middle East and Northern Africa, Southeast Asia (including India), sub-Saharan Africa, the United States and Canada, and global projects, the most frequent roadblocks are funder-created obstacles. Specifically, in Southeast Asia (including India) projects, 57% of roadblocks are funder-created obstacles. In Latin America and the Caribbean, however, the most frequent roadblocks are acts of God or market economics.

The report divides these obstacles into three umbrella categories–organisation misfortune, acts of God/market economics, and funder-created obstacles. Each category contains sub-categories which provide further emphasis on the respective challenge in detail.

Source: Open Road Alliance

There are three specific funder-created obstacles–change in funder strategy, delay of disbursement, and funder policy inflexibility are the most frequently occurring roadblocks across all sectors, funder types, project types, geographic focus, and organisation size, with only some exceptions.

Funders are frequently–if unintentionally–contributing to disruptions to project implementation and threatening the impact of their own investments. The analysis also found—by examining the individual stories told by applicants–that most applicants cited failed communication or poor expectation setting with their original funder.

During the analysis, whenever applicants reported a change in funder strategy as the roadblock, often that change did not occur out of the blue. Rather, nonprofits and social enterprises were informed of an upcoming shift but were reassured (often multiple times) that they would not be affected. Then, at the last minute, these assurances were reversed and applicants were informed that they would not receive funding because of a change in funder strategy. The main funder of a savings project in India, for instance, did a strategy refresh and decided to no longer target projects in India, cutting off funding despite a multi-year commitment.

Likewise, delay of disbursement largely represents scenarios in which a specific date or timeline was given to the nonprofit or social enterprise by the funder, and despite repeated assurances, receipt of funds was significantly delayed to the point of threatening the viability of the project and, in some cases, the organisation itself.

In the case of funder policy inflexibility, ORA found that funders inadvertently undercut their own investments due to internal red tape, despite genuinely wanting to assist their grantees.

In one classic example, a foundation with more than USD 1 billion in endowed funds referred one of its grantees to Open Road because it could not access an internal mechanism to provide an interim USD 90,000 grant to the project between grant cycles. Without the USD 90,000, the grantee–whom the foundation touted as the most impactful project in that particular portfolio–would have been unable to meet payroll. As this data indicates, the actions (or often, inactions) that funders take have material consequences for the organisations they partner with.

The prevalence of funder-created obstacles suggests that funders have the opportunity to significantly maximise impact by re-evaluating their grantmaking and investment practices to determine what changes can better serve the needs of their partners.

Source: CC-BY-SA-4.0

Exceptions

A few exceptions to the analysed data (by individual roadblocks) were agriculture and health, where funder-created obstacles were not the most common roadblocks. Agriculture projects are disproportionately affected by weather (falling under the acts of God/market economics category).

Health projects are disproportionately affected by partner problems (falling under the organisation misfortune category), defined as a scenario in which the actions of a third party threaten to derail the project. While it is unclear from the data why this is the case, one hypothesis is that since most healthcare projects work at a very localised community level, by necessity they are more dependent on local partners and/or local/regional/federal governing bodies than projects focused on other sectors.

Another area where funder-created obstacles is not the primary roadblock is projects funded by family foundations. Their hypothesis is that since family foundations tend to be smaller, they enjoy more flexibility, greater speed, and more direct communication with their grantees than government funders or larger institutional donors.

Reduce roadblocks? How?

The implications of this analysis are sobering because this data suggests that the biggest barrier for nonprofits and social enterprises are their own funders.

Based on this data, along with additional research by Open Road, this study suggests two ways forward that promise to offer the greatest reduction in roadblocks:

The issues of change in funder strategy and delay in disbursement become major roadblocks when clarity and accuracy of funder-grantee communications are compromised. The main difficulties arise primarily from what is communicated, rather than how often. Whether or not they intend it, their comments–no matter how unofficial or informal –often translate into real-life budget and cash flow projections in the plans and timelines of their partners. When promises are unfulfilled, decisions reversed, or delivery of funds delayed, grantees or investees often do not have the ability to absorb costs or pivot to alternate sources of funding within short time frames.

Organisations should also expect a bit more uncertainty in their funder relationships and, where at all possible, adjust budget projections accordingly. Moreover, this study offers a valuable window into internal funder constraints, an area often invisible to grantees. At larger institutions, for example, programme officers themselves may be misinformed about the availability of funds or a new strategic direction. In five years of working with foundations large and small, Open Road has never met a funder who intentionally misled its grantee. The dataset also includes stories where grantees themselves failed to communicate their cash-flow needs because they didn’t want to seem ‘pushy’ or ‘over-ask’.

Looking at the third most common roadblock, funder policy inflexibility, the correctional course of action is suggested in the roadblock itself: flexibility. Too often, funders treat their current grantmaking procedures as inviolable law. Many of the applicants in this dataset were initially referred to ORA by other funders who say they want to help their grantees but can’t because ‘it’s against policy’ or ‘we don’t have a procedure for that’ or ‘we don’t have the money’, which typically just means they didn’t budget for it. Changing or adjusting established procedures is difficult. However, this study suggests that changing funder policies to increase flexibility can directly avoid a significant number of impact-threatening roadblocks downstream.

Three specific ideas of more flexible policies include:

- Adjusting grant cycles to meet grantee cash flow needs (rather than funder convenience).

- Including contingency funds in annual grantmaking budgets with the expectation that some grantee, somewhere, will need additional funding between grant cycles.

- Reducing limitations on what grant money can be spent on and when it can be spent.

To read the whole report, click here.

*Priyanka Dhaundiyal contributed to this article.