The most excluded person can be the hardest to reach. For instance, when an eye camp is held for a cluster of villages, those with acute blindness or struggling with lack of mobility, those located at the remotest distance socially, and excluded minorities and seniors find it most challenging to access the service. India is committed to bridging this last-mile gap as part of the UN’s global mandate, under the Pact for the Future 2024, to leave no one behind.

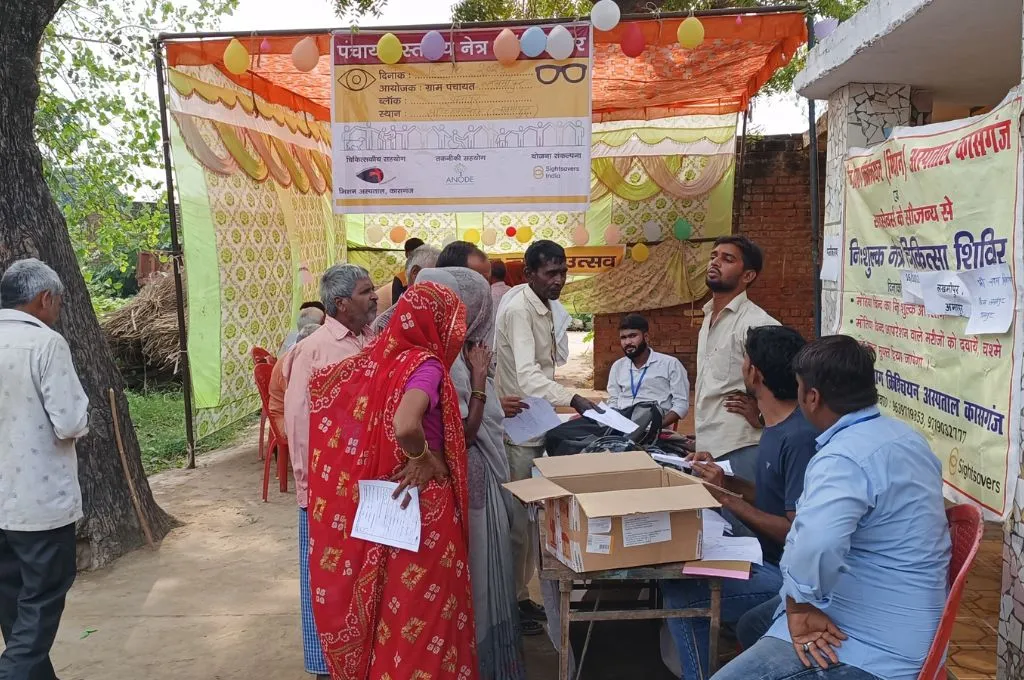

A recent pilot project by Sightsavers India and Anode Governance Lab—focused on eye health and inclusion with an emphasis on local governance as a programming principle—proved that gram panchayats (GPs) are well placed and suited for the localisation of Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). When 30 GPs in three districts of Kasganj, Uttar Pradesh, took the lead in addressing blindness in the village, it turned out to be strong evidence for the fact that if Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) engage with the objectives of universal health and social inclusion, it furthers not only SDGs but also helps GPs forge their political identity and expand their role.

There are frameworks for PRI involvement in health and disability

In the past five years, there has been an increasing realisation as well as pressure for the localisation of the SDGs because understanding the complexities of challenges on the ground and designing effective solutions requires a localised approach. As a democratic institution, the GP plays a crucial role in developing plans tailored to the specific needs of its community. In India, 17 SDGs have been translated into nine priority areas for the GPs. The Panchayat Development Index committee has prepared a framework to assess panchayats on poverty reduction, social inclusion, health, education, water security, sanitation, infrastructure, livelihoods, and governance. Thus, PRIs have the framework they need to prioritise the civic services and amenities their village needs, choose the relevant Localised Sustainable Development Goal (LSDG), and build it into their plan and budget.

From the legal perspectives too, PRIs have the mandate to engage with health and disability. The National Health Policy (NHP), 2017, envisages a preventive and promotive healthcare orientation and universal access to healthcare services. Based on the NHP 2017, the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) empowers PRIs to lead public health management at district and sub-district levels. About eight states have devolved health responsibilities to PRIs. The Rights of Persons with Disabilities (RPwD) Act, 2016, tasks local authorities—including panchayats and municipalities—with the responsibility of ensuring accessibility, inclusive education, healthcare, employment support, social security, and rehabilitation services for persons with disabilities. They can do this by developing disability-friendly infrastructure; making public spaces, transport, and services more accessible; and promoting awareness and sensitisation to address discrimination.

GPs must look beyond infrastructure and livelihoods

A substantial portion of resources for the development of panchayats is provided by the Union Government through various schemes. Centrally Sponsored Schemes (CSSs) such as Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA), Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), and Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana-Gramin (PMAYG) envisage the role and responsibility of panchayats. Most GPs focus on addressing a village’s legitimate needs of infrastructure and livelihoods, for which they receive funds under these schemes. These are important areas of work and bring tangible and visible results, crucial for an elected body. However, as seen during the project, bridging gaps in access to basic rights on health, education, and inclusion can create pathways for deeper engagement between GPs and citizens and build a positive identity for panchayats.

For the longest time though, these services have been the domain of government departments. They are overseen by parallel structures set up by the respective departments, with the token presence of a panchayat member. For increased decentralisation, GPs should take on the assessment and evaluation of health, education, and disability-inclusion programmes and schemes run by the government in their geography and jurisdiction. An optimal GP could go even further and aggregate the needs of the community and create demand-based plans. GPs have access to funds tied to areas such as water and sanitation but can use untied finance for the specific needs of their villages.

Women are often dependent on family members for access to healthcare services.

In many cases, government departments and services are concentrated at the district level, creating barriers to essential services, especially for vulnerable groups. GPs have the potential to bridge this gap by facilitating and bringing services closer to the community, ensuring better accessibility and inclusion.

GPs are not always aware that they can do this. They may not have the confidence to navigate the administrative system. Facilitating them to host eye camps helped approximately 30 GPs see their role in a new light and provided them with experiential learning. More such interventions could increase their capacity and knowledge and make them proactive about the softer aspects and of community life in their villages.

There is complacency around many forms of disability

When we held awareness sessions before the eye camps, most members of the community said there was no discrimination in their village. Because blindness is not fatal, there is complacency around it. For instance, blindness generally occurs after a certain age and the oldest people suffer from acute forms. The social mores are such that it is acceptable for the old to live with it. Again, women are often dependent on family members for access to healthcare services at a cluster- or block-level service. There is also ignorance around how much the quality of life of patients can be improved emotionally, socio-economically, and culturally with small interventions. This is true for many other disabilities, which are often surrounded in myth.

Conversations about disability-adjusted life years (DALYs)—a measure of the number of years lost due to ill health and disability—backed by data, and sensitisation sessions helped members of GPs become more aware of these issues. They realised that different kinds of disabilities—vision or hearing impairment, mobility challenges, mental illness—and the economic, cultural, and social barriers around them were hampering the quality of many lives, and that they could be improved substantially. As the conversations increased, GP members started recalling people who had been living in isolation because of their disability and brought them to our attention.

GP members had to feel empowered to drive change

In the Kasganj district of Uttar Pradesh where this pilot project was carried out, there were many quiescent or inactive GPs. The brief initial training was either inadequate or forgotten. In some villages, the GPs were equated with the pradhan (village head) and the eight to 12 ward members were unaware of their identity as ward members. They did not have regular meetings, and when they did they met at the house of the pradhan instead of the Panchayat Bhavan. Gram Panchayat Development Plans (GPDPs) were mostly prepared and uploaded at the block level instead of the village level, and GP members were not aware of the funds available to them.

Initially, only 20–30 percent of the GP members engaged with the initiative on eye health. When the meetings were shifted from the pradhan’s house to a common space, more of them got involved. Sessions with each GP on their role in disability and social inclusion led to increased momentum in the community about identifying people with disabilities.

Consequently, as they conducted eye camps, pradhans and GP members were able to bring tangible positive results for their constituency. When the impact of an intervention, such as sight restoration, on an individual and the community becomes evident, it encourages a shift in perspective. It alters the way the GPs see themselves and how they are perceived in the community, and generates goodwill and gives them social and political identity.

GPs play a critical role in gathering data from their community

Village-level data in various government departments is usually not uniform and consistent. This can be corrected by leveraging the GPs. As elected members belong to the community, they can update and correct information on the number of people above the age of 50 requiring eye check-ups, those with disabilities, the kinds of disabilities, or enabling assets in the area such as inclusive schools and ramps in public places. One of the key aspects of the programme was to support and guide GP members in data collection, including household data.

Community awareness and sensitisation drives also helped build their understanding of community needs. Many individuals are excluded from government schemes because they lack documents, such as the Unique Disability Identity Card (UDID). GPs helped more people with disabilities in registration and to avail social security schemes and benefits. Pilot health camps can build the knowledge and capacity of GPs to navigate the public health and administrative system. It can lead them to become the aggregators of the unique needs and demands of their villages. For instance, after the eye camps, GP members in the target districts are planning more initiatives with general physicians for health issues such as blood pressure, diabetes, and viral fever.

GPs can be powerful enablers of the SDGs through targeted actions

As the quality of awareness in the communities increases, the capacity of the public medical system will also need to grow. India will require more doctors, surgeons, and specialists in rural areas. Through targeted actions, transaction costs of bringing goods and services will decrease, enabling better utilisation of public funds. Donors and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) firms, for their part, need to eschew stereotypes that GPs are entangled in corruption and bureaucracy and view them as implementors of the SDGs. They may see better results on the mandatory Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) framework when they work with the GPs.

Health, disability, and social inclusion initiatives can help GPs transition from being mere recipients of funds or implementation vehicles for schemes to empowered institutions that create their own plans based on the unique needs of their villages. This can be achieved through focused effort to strengthen their capacity, build their structures and processes, and, most importantly, enable higher engagement of elected members in local governance.

Pramod Kumar Tripathy, Urja Arora, and Namrata Mehta from Sightsavers India contributed to this article.

—