With 34 percent of people aged between 15 and 29 years, India has the world’s largest adolescent and youth population. Although it is often assumed that this will result in a pool of workers who can contribute to India’s economic growth, the reality is quite different. A majority of young people in India either do not have the relevant education and skills to be meaningfully employed or suffer from the absence of enabling opportunities. This is particularly true for youth from marginalised communities—especially girls and non-binary individuals—who have never enrolled in schools or have dropped out.

According to the latest UDISE+ report, approximately 5.6 million students dropped out at the secondary school level in 2020–21.1 In 2019, more than 30 percent of Indian youth in the age group of 15–29 years were not in education, employment, or training. Women constitute 57 percent of this group. Economic migration, caste-based discrimination, early and forced marriages, and gendered control on mobility are some of the structural barriers that result in dropouts. However, these problems manifest in the form of disinterest in studies, irregular attendance, or the absence of relevant government documents, such as an Aadhaar card or domicile certificate, that are required for admission. Engaging exclusively with these symptoms of the problem often disregards the deep-seated structural barriers that are at its root.

The draft National Youth Policy

To address many of the challenges facing India’s youth, the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports recently released a draft of the National Youth Policy (NYP) 2021, seeking to replace the previous NYP 2014. The policy has a 10-year vision for youth development in the following areas: education, employment and entrepreneurship, youth leadership and development, health, fitness, sports, and social justice. In line with the National Education Policy (NEP) and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the policy recognises the issue of dropouts and engages at length with possible strategies to address the problem.

1. Focusing on the individual rather than the structure

One of the strategies suggested by the NYP 2021 to ensure that at-risk youth stay in school is counselling them and mobilising ‘school–community–parent partnerships to encourage them to stay in school’. Without going into the specifics, it also suggests providing merit-based bank loans to ‘exceptional’ students and creating an online dashboard for youth to access any information related to education.

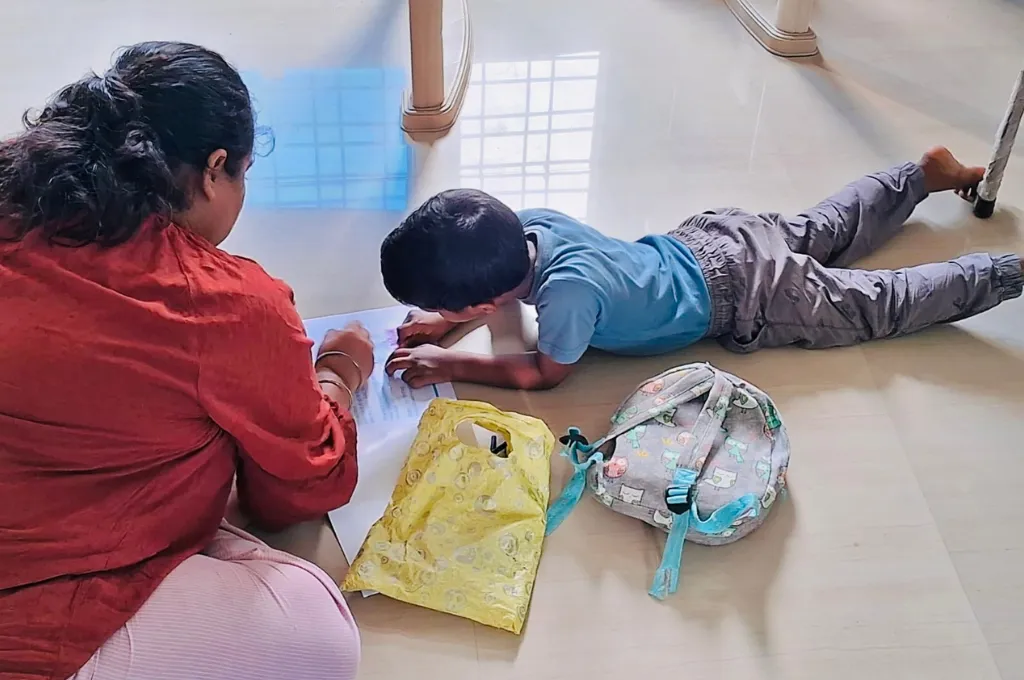

Through Nirantar’s work with out-of-school children and youth in the resettlement colonies of Delhi and Uttar Pradesh, we have found that counselling is an inadequate response to the structural barriers that push young people out of the education system. A number of studies and reports have also shown that dropping out is not a matter of motivation but a consequence of systemic barriers. The problem with the draft NYP’s approach is that it puts the onus of staying in school on the individual learner. By doing so, dropping out is assumed to be a personal problem that mere ‘encouragement’ or counselling can resolve.

Such a solution ignores the structural barriers of caste, class, gender, religion, and ethnicity. This is further reflected by the fact that the policy encourages ‘merit-based bank loans’ instead of need-based ones. Need-based loans recognise the various barriers that impede students from performing well academically. By providing financial assistance to students from the most marginalised sections of society, these loans can help prevent dropouts. Education loans are also not an option for under-resourced families that are already struggling to sustain themselves. By rewarding ‘exceptional’ students based on meritocracy, while simultaneously ignoring the root causes of poor performance, the policy risks further marginalising students from different caste locations and with different abilities, and sex and gender identities.

Additionally, a study by Azim Premji University estimates that approximately 60 percent of students in India do not have internet access. Without addressing this disproportionate gap in access to digital devices, the feasibility of an online dashboard remains doubtful.

2. No clarity on data systems

To reintegrate dropout youths into the education system, the policy suggests creating a comprehensive data system that is responsible for systematically identifying and tracking out-of-school youth.

However, there is little to no information about the logistics of this comprehensive data system. Data systems run the risk of social profiling based on caste, class, religion, and sexuality leading to discriminatory practices. Currently, no mechanism has been envisioned to address these challenges. Additionally, migration is one of the major causes of dropouts but no clarity has been provided on how this data system will help in keeping migratory youth in the education system. This should be seen in conjunction with the fact that even after 13 years of the RTE Act, the migrant population has seen very limited benefits.

3. An absence of well-researched solutions

To address waning enrolment rates at the secondary level, the policy recommends building new schools where there are none. In areas with low demand, it suggests upgrading the schools with better information and communication technologies and improved transport facilities. For low enrolment in colleges, the policy pushes for ‘stronger regulation of private institutes’.

Low enrolment numbers at the secondary school level are not new. To address this, in 2017, NITI Aayog launched its educational reform programme called Sustainable Action for Transforming Human Capital in Education (SATH-E) in Odisha, Jharkhand, and Madhya Pradesh. Under this programme, schools with low enrolment were closed and merged with the nearest government schools. So far, more than 4,800 schools have been shut down. However, SATH-E proved to be a failure. In Odisha, instead of bringing children back to school, it discouraged access as students now had to travel further away to the newly merged schools. Recognising this, the Odisha High Court issued a stay on the merger of the remaining 8,000 schools and directed the School and Mass Education Department of Odisha to find the cause behind low enrolment instead of shutting down schools.

Another possible reason for low enrolment levels is the dwindling teacher–pupil ratio.

Even though the draft policy proposes providing transport facilities, it does not offer any clarity on how it will reach those living in remote and difficult geographies. Another possible reason for low enrolment levels is the dwindling teacher–pupil ratio. The draft NYP’s approach of building new schools in low-demand areas without identifying reasons for low enrolment is likely to be counterproductive.

Additionally, to address the problem of low enrolment rates in colleges, the policy emphasises a stronger regulation of private institutes ‘to ensure that education imparted is of value to the youth’. This is effectively in line with NEP’s graded autonomy model that pushes for the privatisation of education. The perils of such a model have been debated and protested at length since UGC granted graded autonomy to 60 educational institutions in 2018. Graded autonomy disguised as ‘stronger regulation of private institutions’ will only lead to substantial hikes in student fees, which instead of ensuring enrolment will push youth further out of higher education.

4. Lack of sexuality education programmes

India is a signatory to international bodies such as UNESCO, the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESR), and Conventions of the Rights of the Child (CRC) that have routinely focused on the importance of comprehensive sexual education for adolescents and have recognised sexuality education as a right to health and survival. However, the draft NYP makes no mention of this. A lack of sexuality education undermines adolescents’ ability to successfully navigate the myths associated with sexuality and sexual health. For instance, a report by Dasra suggests that 23 percent of girls drop out of school after reaching puberty. The inability to manage their periods at school, teenage pregnancies, along with several health risks associated with adopting unhygienic menstrual hygiene practices often cause young girls to discontinue their education.

Instead, the policy’s final strategy regarding dropout youths involves developing national-level programmes covering a wide range of skills, of which ‘childcare and family welfare education’ is one. Not only does this assume that childbearing is expected from the youth, but it also provides no clarity on what ‘family welfare education’ entails. Does the state envision heteronormative and traditional family structures, or does it include an awareness of sexual diversity? Will this education equip adolescents to better understand their sexual and reproductive rights? Will education related to childcare be extended to single mothers?

The way forward

With unemployment at 6.8 percent in 2022, there is an urgent need for the government to rethink its strategies for addressing dropout youths. This must begin with an acknowledgement of the structural inequities and barriers that force young people to leave their education midway. Several organisations such as the Centre for Research and Policy (CPR), Pratham Foundation, Dasra, and Care India are working to document this, and their insights will prove useful for the government in its planning processes.

To help reintegrate youth into the education system, the draft NYP also envisions partnerships with nonprofits and private sector organisations to create non-formal education centres. While formal education is highly structured and rigid, non-formal education centres are flexible in terms of organisation, timing and duration of teaching and learning, age group of learners, methodology of instruction, and evaluation procedures. These features make non-formal education a crucial pathway for reaching out to the most marginalised sections of children and youth.

Rather than focusing on reintegrating youth into the school system, non-formal education spaces can serve as a robust educational alternative.

At Nirantar, our work with dropout youths has also shown us the merits of using non-formal education spaces as an alternative to address the issue of dropouts. Rather than focusing on reintegrating youth into the school system, these spaces can serve as a robust educational alternative. Not only are they mindful of the structural barriers that cause students to drop out, but they also focus on skill building and training sessions (in addition to textbook education) as strategies to encourage young people to continue learning. While these alternative educational centres carry great potential to challenge the issue of dropouts, educational policies such as the RTE Act and Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao should be simultaneously strengthened.

It’s high time that India makes policies keeping in mind the structural challenges that confront a significant population of its youth, particularly women. Instead of using counselling as a post-facto strategy to address dropouts, policies that prevent dropouts in the first place should be prioritised. Efforts must also be made to recognise the reasons behind low enrolment and dropout rates. And finally, to truly empower India’s youth, the NYP must recognise the significance of comprehensive sexuality education and fulfil its international commitments to impart the same.

Ankita Dhar Karmakar, Sohnee Harshey, and Archana Dwivedi contributed to this piece.

—

Footnotes:

- According to the UDISE+ report, the total number of students enrolled in secondary schools is 39 million (table 1, p. 62). The total dropout rate of students from these schools is 14.6 percent (p. 109) or 5.6 million.

—

Know more

- Read this report to understand the factors behind early and child marriage and how it leads to dropouts.

- Understand the impact of COVID-19 on schoolgoing children.

- Learn more about what young adults in India see as integral to their well-being.