Discussions on outcomes-based funding (OBF) in the social impact sphere are constantly growing. OBF is a financing model where funds are allocated to programmes or institutions based on achieving specific, measurable outcomes instead of on inputs or activities. The OBF instrument—which can be a development impact bond (DIB), impact guarantee, result-based financing contract, or social success note—funds projects in education, livelihood, and skilling, and is tied to certain quantifiable results such as learning outcomes, enrolment, completion rates, employment rates, or health outcomes. In such a model, financial support is closely linked to the achievement of predefined targets. This shifts the focus from inputs (for instance, the number of students enrolled) to outputs (such as test scores and job placements).

Many of these OBF projects have led to significant improvements. Civil society organisations and funders proudly display data showing success, often portraying a picture of enhancing outcomes. But as someone who has been involved in an OBF project and has also worked in the field of inclusion for more than two decades, I must ask: Who is being left out of these success stories? While OBF can drive efficiency and measurable progress, it often lacks a focus on inclusion.

Averages mask inequality

OBF instruments are designed to be flexible and customisable, with targets mutually agreed upon by funders and participants. The flexibility in defining outcomes is also with a view to actively incentivise inclusion. In fact, globally, many OBF programmes specifically target underserved populations, such as refugees or persons with disabilities.

However, in my experience with OBF projects in India, funding has relied on average scores as a key metric in all but one project. This means that the performance of the entire group or cohort is measured collectively to assess success. If a school, for example, sees an average improvement in student performance on standardised tests, the programme receives the expected funding. But does this accurately represent learning across children of all abilities?

We are, in effect, choosing to leave behind the most marginalised children.

This is the danger of depending on average or aggregated outcomes—it allows us to celebrate progress for the majority while ignoring those most in need of support. For example, a training programme that shows an average job placement rate of 70 percent may receive funding, even though a segment of the cohort (for example, people with disabilities or those from marginalised backgrounds) faces significant barriers that are not captured in the overall metric. When we measure success by averaging outcomes across a cohort, we effectively prioritise the achievements of the top 25 percent and the relative gains of the middle groups. Their success boosts the overall numbers, making the intervention seem effective. Meanwhile, the bottom 25–30 percent of children and young adults who face multidimensional exclusion due to various reasons—such as poverty, disability, health, religion, and gender—remain overlooked and underserved, their needs hidden behind convenient data points.

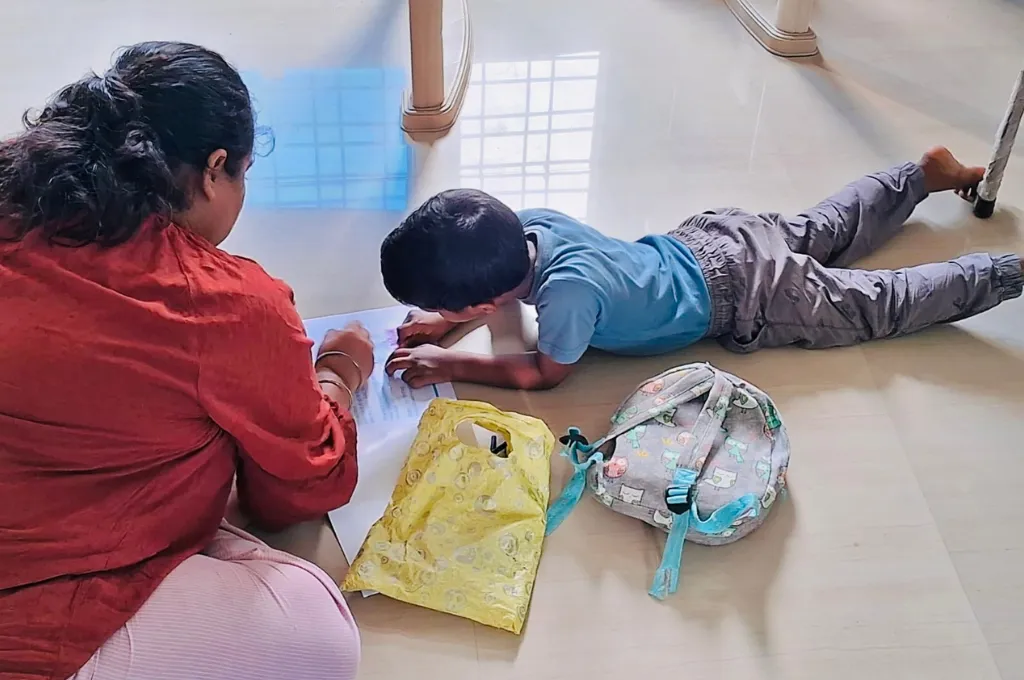

Let’s take another example of a government school where the intervention is linked to funding. When the results are tied to average test score improvements, teachers focus on students who can show quick gains, sidelining those with disabilities, slow learners, and first-generation students who need more support. To meet targets, schools may discourage enrolment of struggling students. This creates a false sense of progress—while averages improve, the most vulnerable children are left behind, reinforcing systemic injustice rather than addressing it.

We are, in effect, choosing to leave behind the most marginalised children—and we must call this what it is: the convenience of exclusion.

This exclusion isn’t accidental—it is built into the very fabric of how we measure success. This holds true for all types of funding where averages are used to make evaluations. We rely on data that makes it easier to claim victory without grappling with the complexities of reaching every child. In doing so, we are prioritising the education of some children over that of others. This is not just a question of methodology, but also a question of rights.

When we stratify data by performance level, the inequality becomes undeniable. The top performers make rapid gains with minimal assistance, while the bottom performers require tailored interventions, additional resources, and targeted support to have any chance of closing the gap. The current system is not designed to meet these needs.

Towards a rights-based approach

If we are truly committed to building an inclusive education system, we need to rethink how we define, measure, and fund success. Most current approaches, centred on efficiency and aggregate gains, fall short of addressing the systemic inequalities that affect vulnerable students. A rights-based approach offers an alternative—one that places the dignity, potential, and progress of every child at the centre of all efforts.

1. Disaggregate performance data

To uncover inequities, we must go beyond overall averages and disaggregate data by performance levels, demographics, and other intersecting factors such as disability, gender, socio-economic status, and location. This will make the invisible visible, highlighting disparities and ensuring that no group is hidden behind aggregate figures. For example, tracking the progress of students in the bottom quartile separately can show whether interventions are proving effective for those who face the most barriers.

2. Focus on equity

Funding and recognition must shift towards programmes that prioritise and demonstrate improvements for the most marginalised groups. This requires changing the metrics of success to reward organisations that take on the challenge of working with the hardest-to-reach children. For instance, funders can provide higher rewards or longer-term support for interventions targeting children with disabilities, those from underserved communities, or those with significant learning delays.

Equity-focused education systems also require accountability mechanisms that track the progress made in closing gaps. Governments, civil society, and funders should regularly report on how their initiatives impact marginalised children, creating transparency for the public and urgency for improvement. Such mechanisms are currently absent, and hence there is a lack of accountability towards the most marginalised.

Additionally, an equity lens means setting ambitious but achievable goals for marginalised groups and celebrating progress, however incremental, in narrowing inequities. For example, in education, instead of aiming for all students to meet the same grade level, we could set goals that are personalised to each child’s starting point and address unique barriers, such as access to resources, gender norms, or community challenges. By tracking small wins—whether in attendance, skills gained, or self-confidence—we can create a system that truly uplifts the most vulnerable. Equity-based metrics should prioritise not just outcomes but also the quality of learning experiences and access to necessary resources for all children.

3. Tailor interventions to address complexity

A rights-based approach acknowledges that different children require different levels and types of support. Children with disabilities or severe learning gaps may need specialised teachers, assistive technologies, smaller class sizes, or individualised learning plans. Investing in these tailored interventions might be more resource-intensive, but it is essential to close learning gaps and uphold every child’s right to education.

This approach also demands that marginalised communities be actively involved in decisions that affect their lives. In the context of education, a school implementing this approach might form a community advisory board that includes parents of children with disabilities or those from backward or Adivasi communities, local activists, and the children themselves. This board would help shape the curriculum, decide on necessary accommodations, and advocate for resources, ensuring that the needs and perspectives of these marginalised groups are at the heart of policy decisions.

A rights-based approach, focused on equity and inclusion, guarantees that all children, especially those most disadvantaged, receive the support they need, fostering a society where everyone can thrive. Without this shift, our commitment to equality remains a hollow promise.

—