India has been undergoing rapid demographic changes for over three decades. With a population of 1.44 billion, it is one of the fastest-growing economies and the world’s most populous country. This growth presents both challenges and opportunities in the realm of public health.

In this data dialogue, we examine how major health indicators have evolved over time.

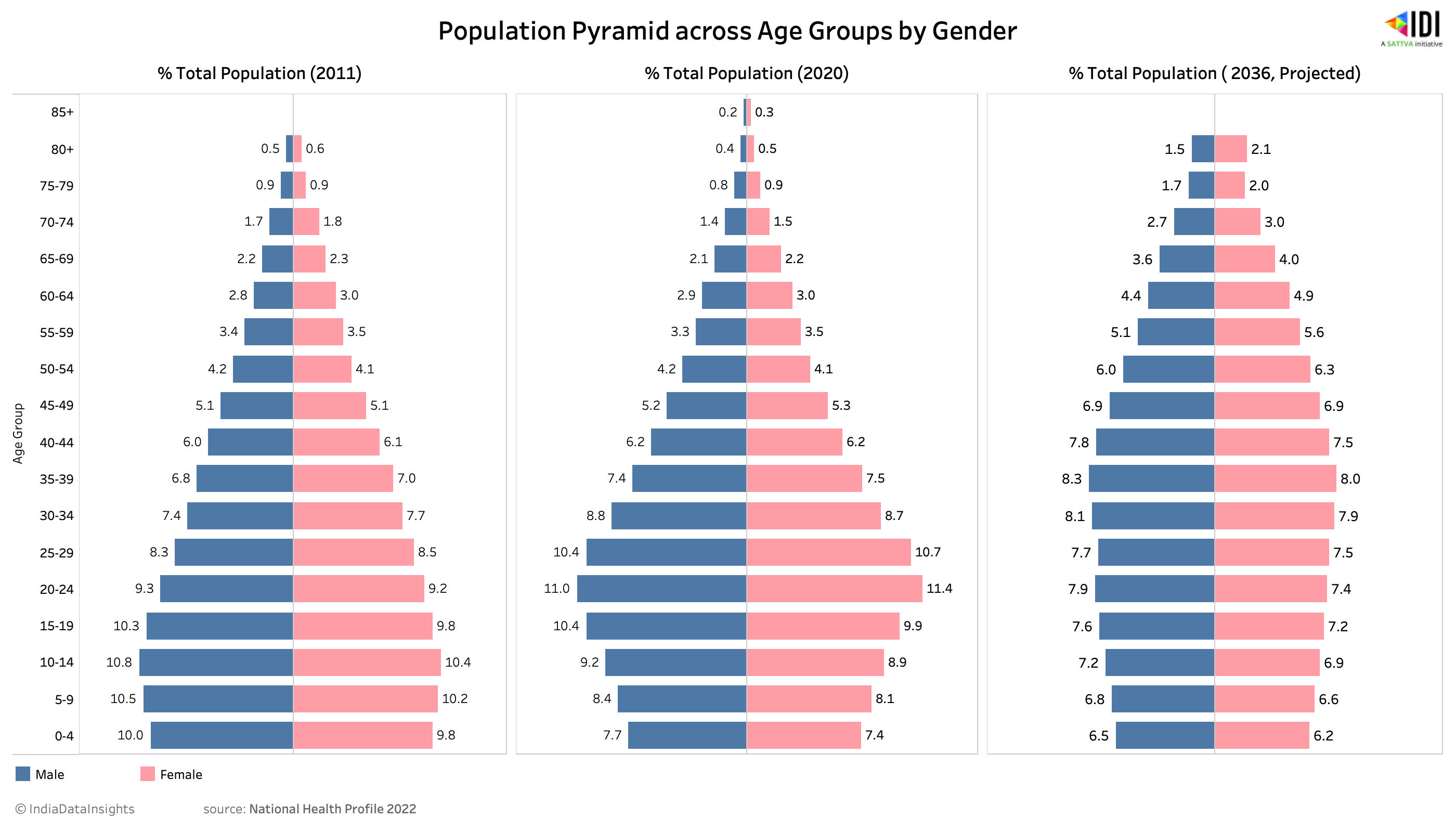

The population pyramids of India reveal notable demographic shifts over the last decades. In 2011, 8.1% of the male population and 8.6% of the female population were aged 60 and above. By 2036, these percentages are projected to increase to 13.9% for men and 16% for women. Meanwhile, the proportion of younger age groups (0-14 years) is expected to decrease from ~30% to ~20%.

These trends highlight India’s transition from a youthful population to a more mature and aging demographic, which will have profound implications for healthcare, social security, and economic policies in the coming years.

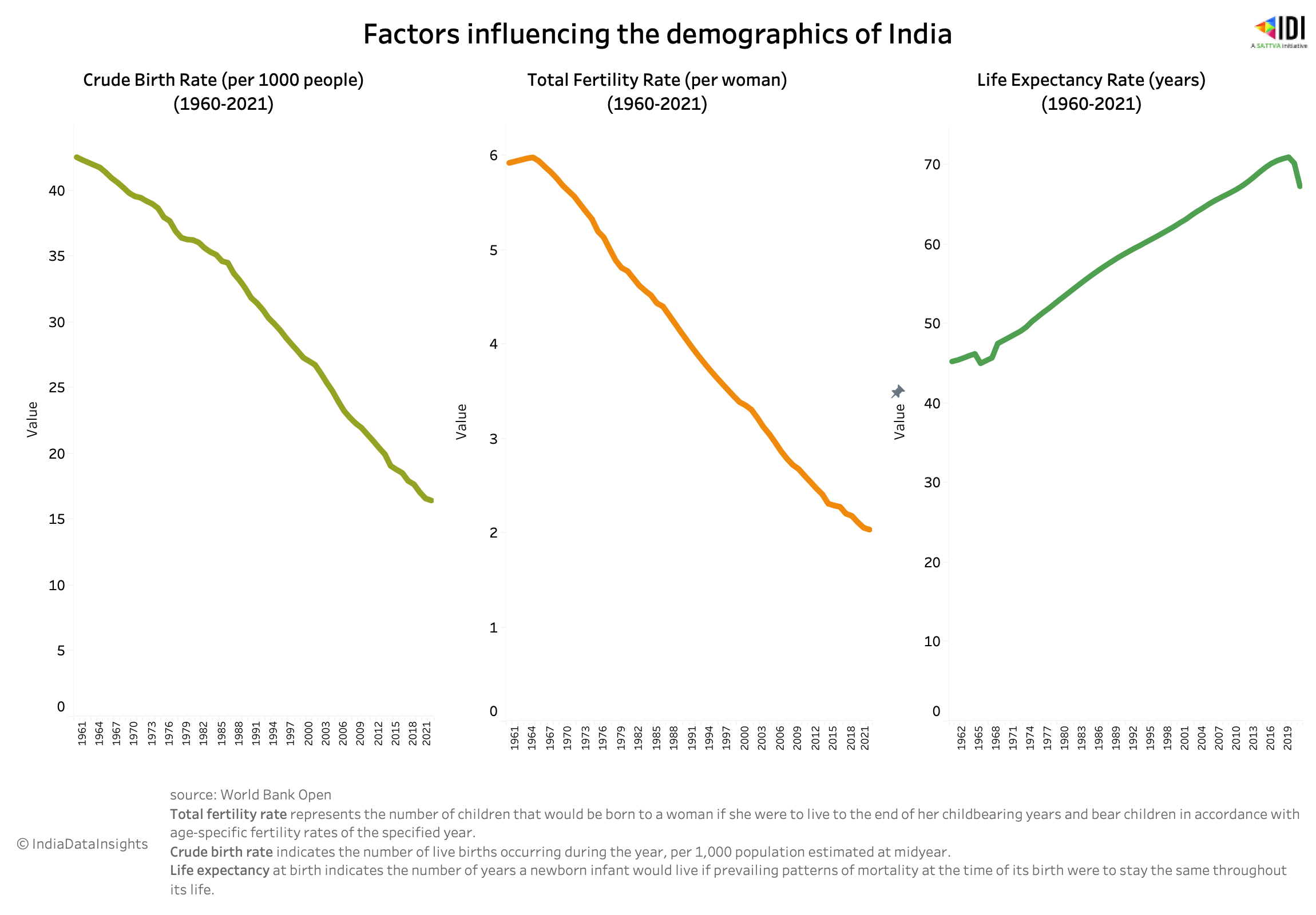

Some of the factors that influence the changing population pyramids are the declining birth rates, declining fertility rates and an increase in life expectancy. In the last seven decades, the crude birth rate and fertility rate per woman declined by more than half, while life expectancy at birth increased by nearly half.

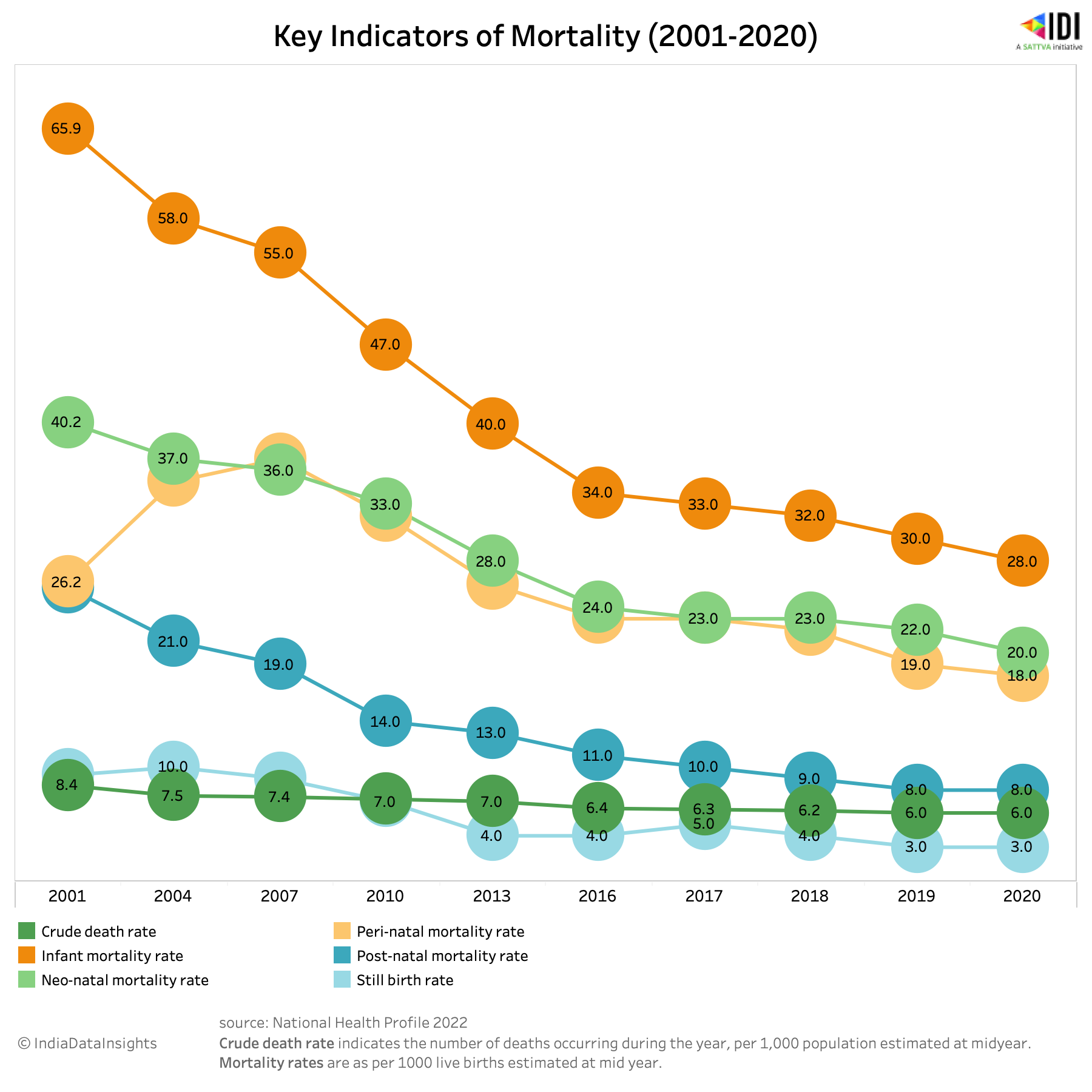

As the country’s population expands and life expectancy increases, mortality indicators have been decreasing. The crude death rate was 19.6 in 1960, and has since seen a substantial ~70% drop. In the last 2 decades, the crude death rate has dropped from 8.4 in 2000 to 6.0 in 2020 However, it has stabilized during this time.

Neonatal mortality in India was at 20 per 1,000 births in 2020. The SDG target for 2030 further aims to reduce this number to at least 12 per 1,000 births, alongside the goal to end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, for which IMR is 28 per 1000 for 2020. These figures indicate that substantial efforts are required for India to meet these high targets.

Overall, the data suggests that changing demographics with decreasing mortality hint towards a parallel change in morbidity in the country.

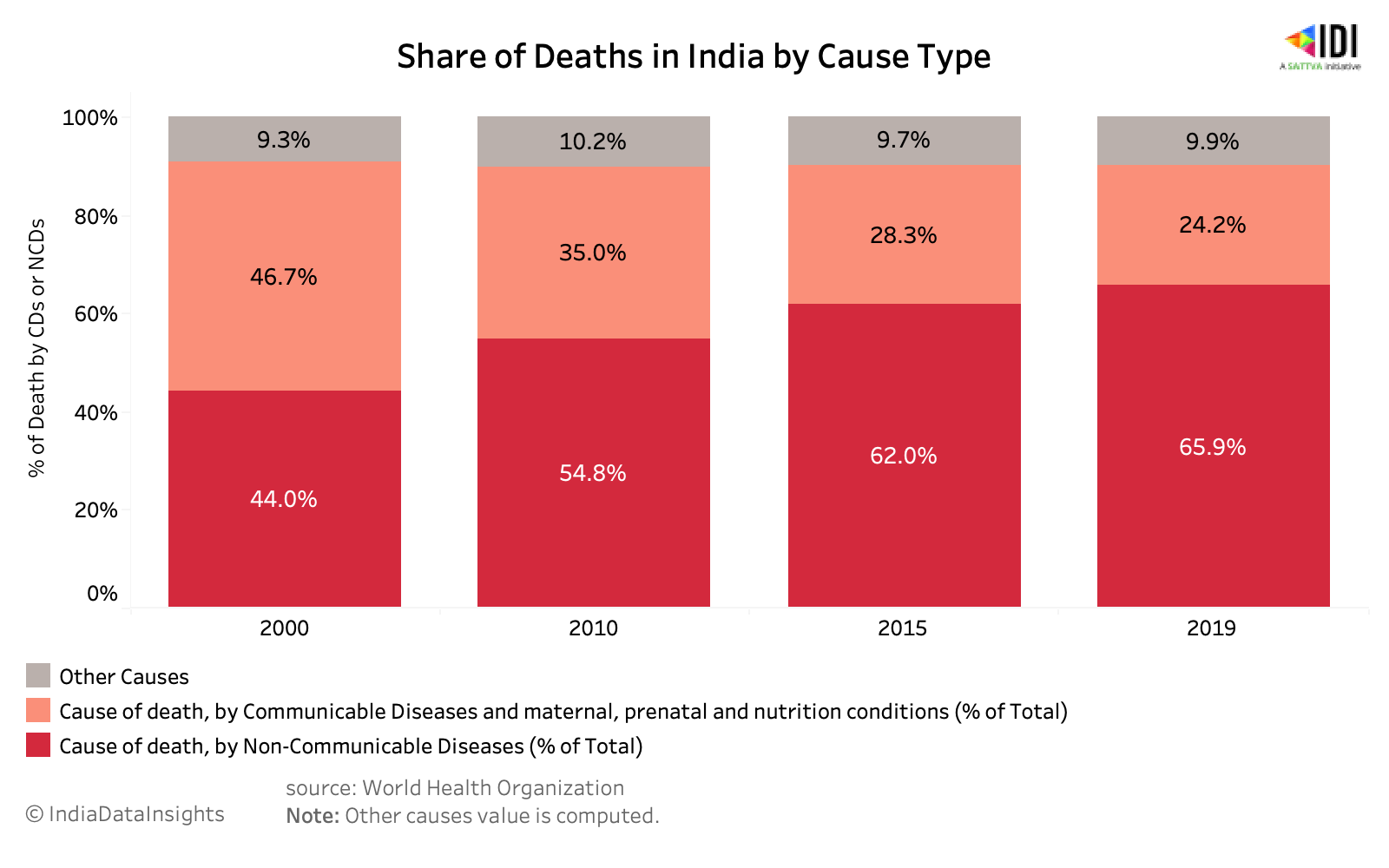

The share of deaths in India shows that morbidity rates have increased drastically in the last two decades, especially for non-communicable diseases. Share of deaths due to NCDs stand at an all-time high of 66% of the total causes of deaths in India.

This shift reflects a unique situation where the country is experiencing low mortality but high morbidity. In 2000, the share of deaths due to CD & NCDs was almost equal (~45%). After two decades, deaths due to NCDs are more than 2.5 times the deaths due to CDs.

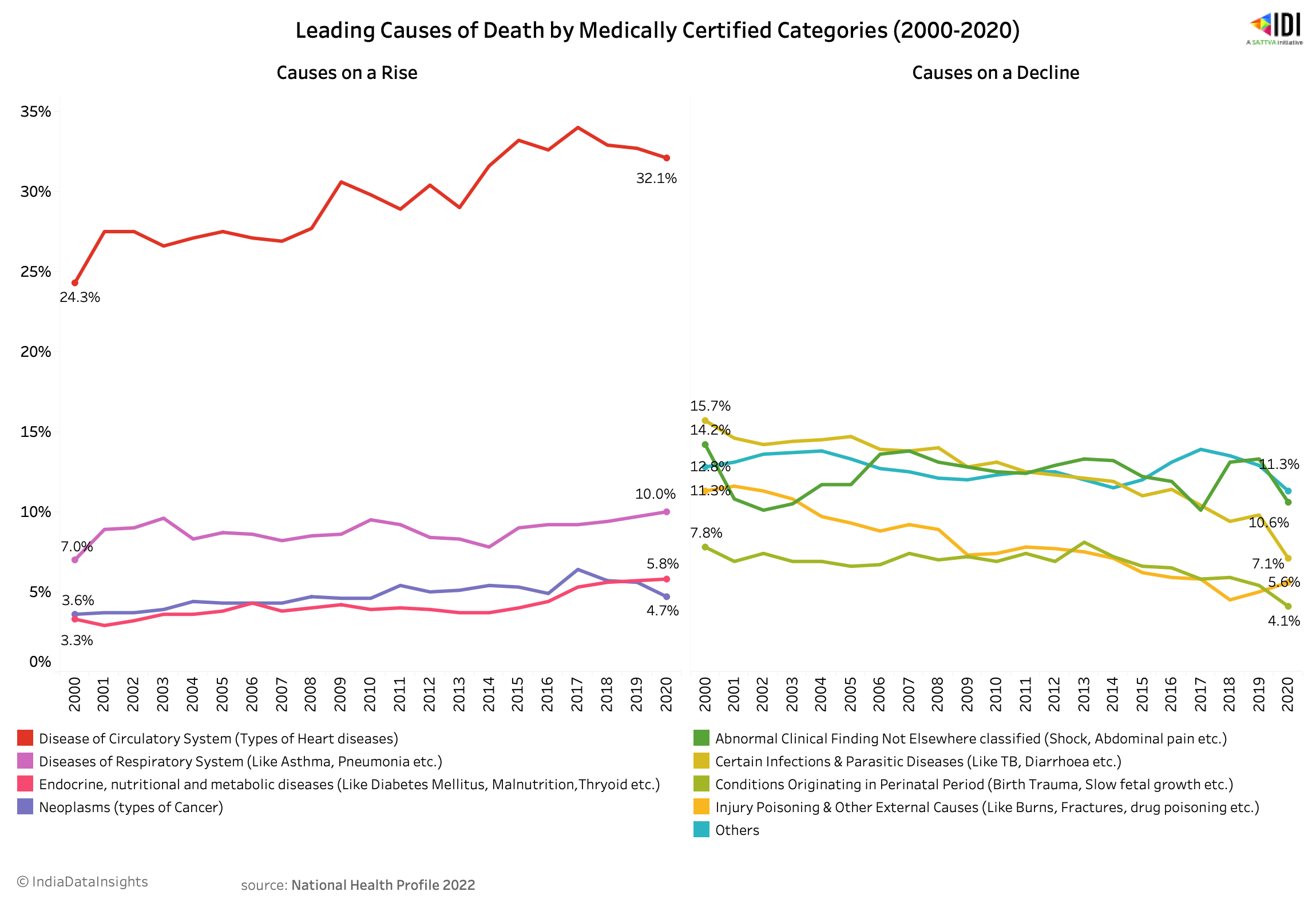

In 2020, there were approximately 81 million registered deaths in India, with 22.2% (around 1.8 million) being medically certified. Of these medically certified deaths, ~80% (1.4 million) were attributed to the eight causes mentioned above.

Diseases of the circulatory system are the leading cause of death and constitute the largest share, 32.1%, of total medically certified deaths in 2020. Deaths from this disease have also increased by one-third over the past 20 years.

During the same time, 5 out of these nine cause groups have shown a declining trend; however, they still remain a significant problem in India and are among the leading causes of death.

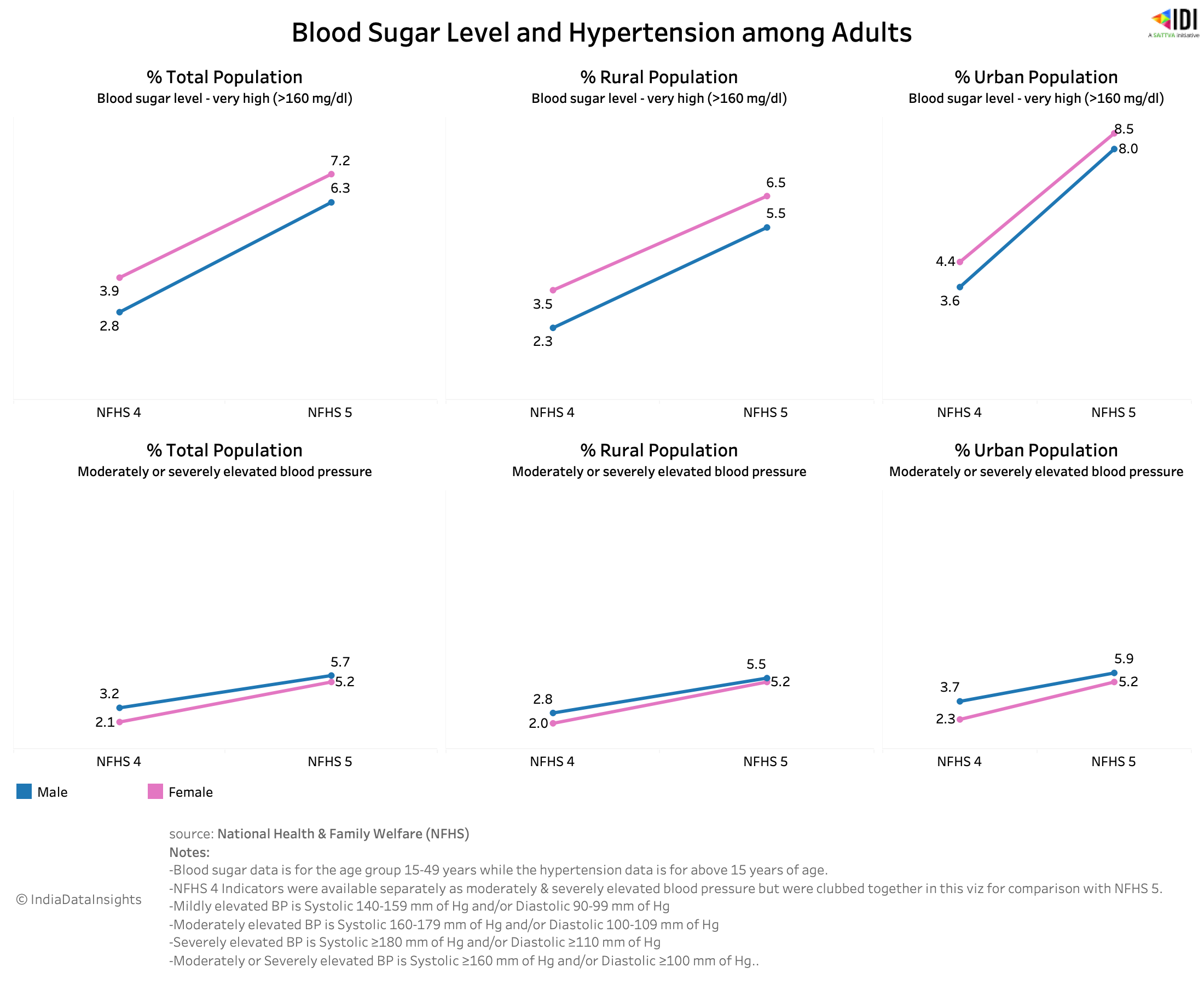

With the increase in chronic diseases, data on lifestyle diseases also reveals a concerning trend: the incidence of “very high” blood sugar levels among adults in India has risen significantly from NFHS 4 (2015-16) to NFHS 5 (2019-21) across all populations (total, rural, urban). This highlights notable gender and urban-rural disparities. Women are more affected by elevated blood sugar levels than men, while men have higher rates of elevated blood pressure compared to women. Urban areas exhibit higher and more rapidly increasing rates compared to rural areas for lifestyle-related diseases.

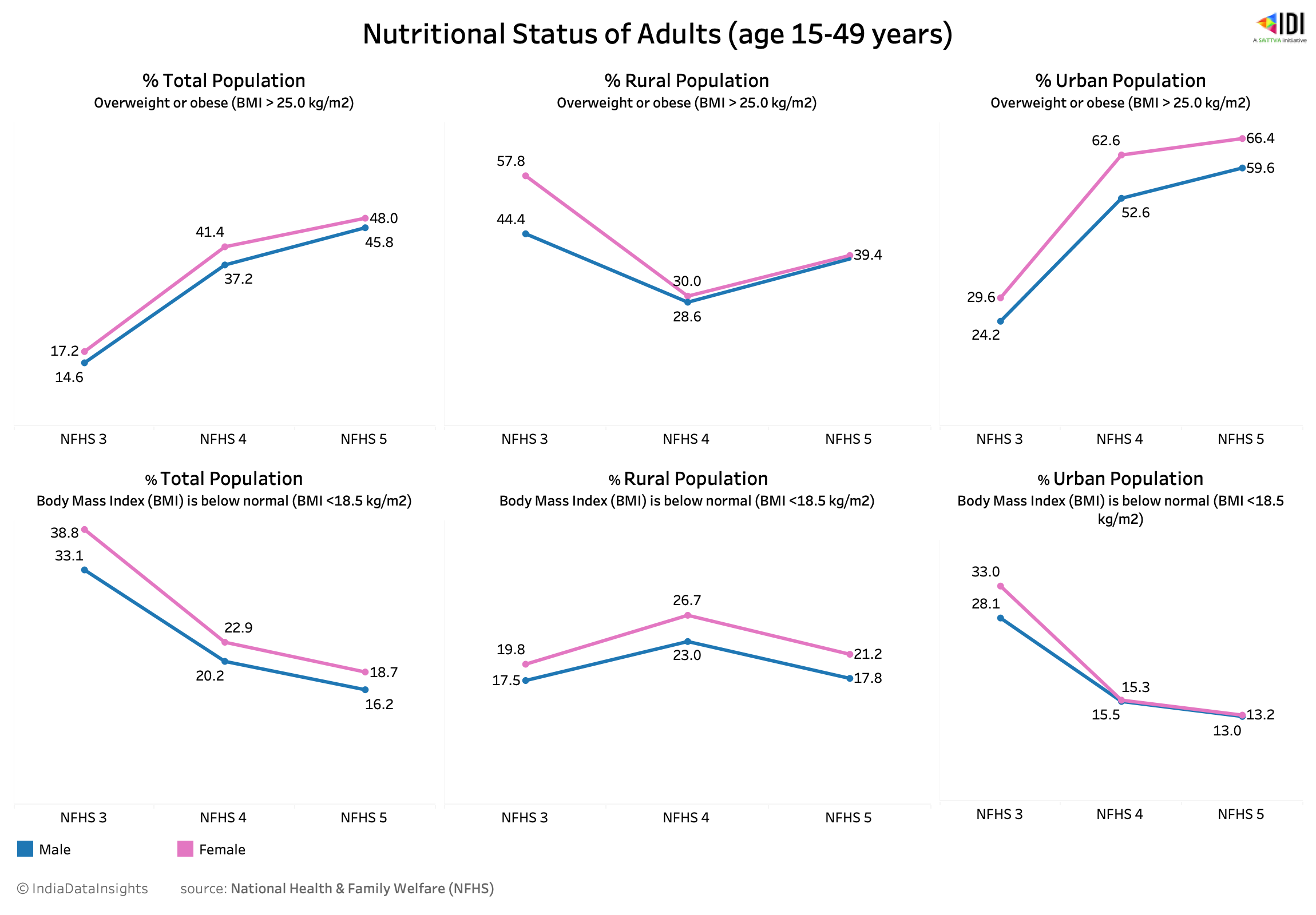

Underlying these lifestyle diseases are the overweight and obesity rates among adults in India, which are also increasing, with notable differences between urban and rural areas and between genders.

The percentage of adults with a below-normal BMI is decreasing, showing improvements in undernutrition, but rising obesity rates present new public health challenges. Women are generally more overweight or obese than men across all areas (total, rural, urban). Urban areas have higher overweight/obesity rates than rural areas, highlighting a significant urban-rural nutritional divide.

Additionally, Women also have higher rates of below-normal BMI in total and rural populations, while urban rates show minor gender differences.

India’s population is moving towards an ageing population with overall mortality rates decreasing but morbidity rates, particularly burden from chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs), rising more than ever. India’s health burden is shifting from high mortality to high morbidity, requiring a focus on preventive care and managing chronic illnesses in an ageing population.

The SDG 3 target by 2030 is to end the epidemics of communicable diseases and reduce premature mortality by one-third from Non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment.

India needs a multi-pronged approach to address these challenges and achieve the SDG Targets. Public health interventions promoting healthy lifestyles, early detection of NCDs, and improved access to healthcare services are crucial. Addressing the urban-rural disparities in nutrition and healthcare access is essential for a healthy future.

This article was originally published on India Data Insights.