COVID-19 has exacerbated existing inequalities. Children in particular have been adversely impacted—they have been pushed further into poverty as their parents lose income sources. This has limited children’s access to health, nutrition, education, and protection.

The share of budget for children was only 2.46 percent of the total Union Budget 2021–22, a reduction from 3.16 percent in 2020–21, and much below the 5 percent recommended by the National Plan of Action for Children 2016. The Union Budget for 2022–23 gives us an opportunity to increase public investment on children so as to ensure their well-being.

Additionally, to ensure effective child budgeting as mentioned in the National Plan of Action 2016, a comprehensive analysis of budgetary provisions for children must be undertaken, which should include total allocation and expenditure by central and state governments as well as panchayats and urban local bodies (ULBs). To strengthen accountability, the Union Government’s Child Budget Statement must include information on actual expenditure on child-focused programmes and schemes.

Save the Children-India makes the following recommendations for the Union Budget 2022–23:

1. Allocate 1.5–2.2 percent of the GDP to provide early childhood education (ECE) services

India’s budget statements do not have a single budget head dedicated to ECE. Disaggregated data on ECE spending within the Integrated Child Development Scheme—the largest government programme that delivers ECE services—is also absent. Calculating the current government spending on this sector is therefore not a straightforward exercise. A study1 commissioned by Save the Children and carried out by CBGA found that India spends about 0.1 percent of its GDP on ECE. Considering that almost 38 percent of India’s children aged 3–6 years do not receive any early childhood education and that the existing services require qualitative upgrades, government spending on ECE must be increased.

The study also concluded that to provide quality ECE services to the 38 percent of children not receiving any at the moment, the government needs to spend at least 0.5 percent of the GDP in addition to its current spending on ECE. When the cost of quality ECE for all children in India was estimated, it was found that to ensure quality education for all current beneficiaries (both government and others) as well as children not covered by any government ECE programme, the budgetary allocation to ECE must be at least 1.5–2.2 percent of India’s GDP.

2. Increase public funding on health to 2.5 percent of the GDP

India’s public health spending as a percentage of the GDP has been low. In 2010–11, the overall spending on health formed 1.3 percent of the GDP. In the ensuing years, until 2016–17, the overall spending on health hovered between 1.2 and 1.3 percent. It increased to 1.4 percent of the GDP in 2016–17 and remained the same for the next few years. The revised estimates for 2019–20 and the budget estimates for 2020–21 show the share of overall spending on health at 1.5 percent and 1.8 percent of the GDP respectively. The increase in 2020–21 is due to increased spending on account of the pandemic.

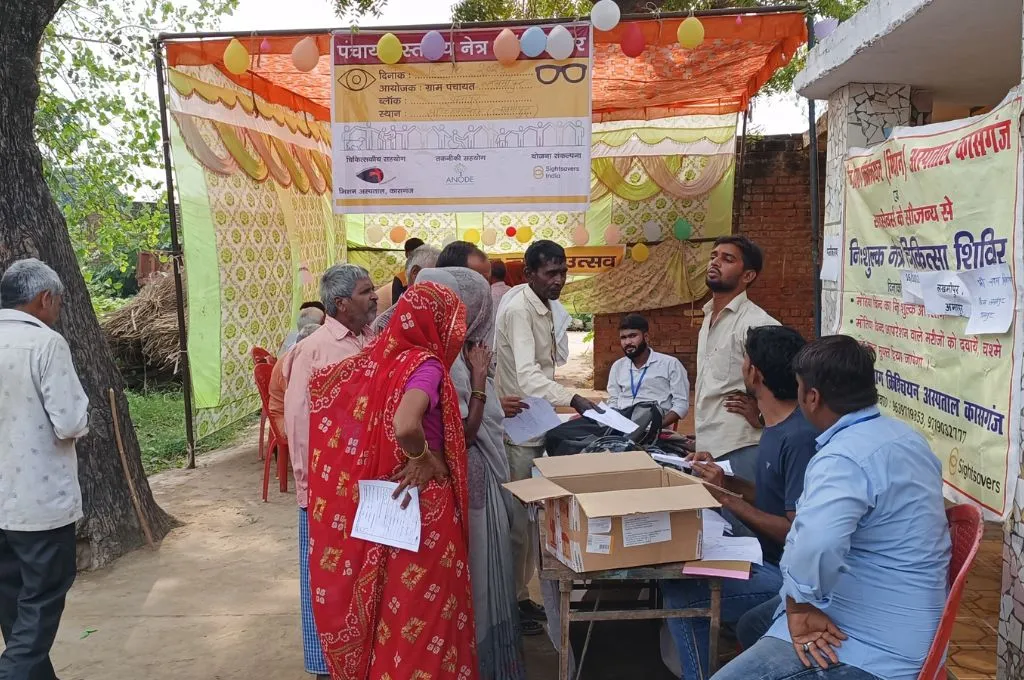

Increasing the budgetary spend on health to 2.5 percent of the GDP will help to ensure inclusive and universal health services for all.

Increasing the budgetary spend on health to 2.5 percent of the GDP, as recommended by the National Health Policy 2017, will help to ensure inclusive and universal health services for all. It will also result in a proportional increase in the share of child health budget.

3. Improve spending on nutrition to ensure adequate access to essential nutrition-specific and nutrition-sensitive services

Nutrition is inherently multisectoral, covering maternal and child health, infant and young child-feeding, micronutrient supplementation, food security, social protection, agriculture, WASH, and more. Consequently, calculating the financing need for nutrition is extraordinarily difficult. Estimates show that India needs around INR 38,500 crore to deliver well on nutritional indicators, especially for the Anganwadi Services Scheme and POSHAN Abhiyaan.

We hope that in the coming budget there will be optimal allocation and better utilisation of schemes related to nutrition. In past years, releases and expenditures for the POSHAN Abhiyaan have been low. The new scheme PM POSHAN is to be extended to students receiving pre-primary education in government and government-aided schools and will require adequate funding as per the revised cost norms and headcount.

Last year, ICDS, POSHAN Abhiyaan, Scheme for Adolescent Girls, and National Crèche Scheme were restructured into Saksham Anganwadi and POSHAN 2.0. Merging and restructuring schemes may carry the advantage of ensuring integration across ministries, but while allocating the budget the sum total must be more than the individual components. However, the budget allocated for Saksham Anganwadi and POSHAN 2.0 was lower than the sum of its individual components from the previous year.

The trend among programmes run by the Ministry of Women and Child Development has been to spend the majority of costs on supplementary nutrition, while the majority of the spending by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has been on immunisation. However, the budget allocation and expenditure must be balanced as per estimates across all nutrition-related interventions. Nutrition financing must prioritise the leave-no-one-behind agenda.

4. Increase the budget for sponsorship and foster care

Under the Integrated Child Protection Scheme, an amount of INR 10 lakh per district is provided for sponsorship and foster care. Foster care is an arrangement whereby children who cannot be adopted legally and whose parents are unable to take care of them live with extended or unrelated family members. Sponsorship is meant to provide financial support to destitute families whose income does not exceed INR 36,000 per annum for metro areas, INR 30,000 per annum for other cities, and INR 24,000 per annum for rural areas.

The annual allocation of INR 10 lakh per district is inadequate to reach all eligible children. In particular, keeping in mind the increase in vulnerability caused by the pandemic, this amount must be increased to cater to the needs of all eligible children.

5. Improve design and enhance budget allocation for key social protection schemes

India needs to increase investment in key social protection programmes to address the increase in household poverty caused by the pandemic. It has been estimated that the number of people in India living below the poverty line has increased to 508–556 million during COVID-19, inclusive of 208–228 million children (assuming that 41 percent of the population comprises children, as per Census 2011). This indicates an increase of between 150 and 199 million people (and, correspondingly, between 61 and 81 million children) living below the poverty line.

Public Distribution System: Despite the nationwide increase in poverty, the design of schemes such as the Public Distribution System (of food grains for the poor), commonly known as PDS, have not been revised to accommodate ‘newly entrant’ people who are now living below the poverty line. Expanding the coverage of PDS would contribute to realising food security for these newly entrant families. The Government of India must expand the coverage of PDS from 80 crore to 100 crore citizens to ensure food security in line with the National Food Security Act.

MGNREGA and National Social Assistance Programme: COVID-19 has caused an increase in unemployment and underemployment in India, resulting in an increase in child poverty risks including reduction in food intake (hunger), increase in child labour, and early marriage. To address these risks, the Government of India must update the design of schemes such as MGNREGA (flagship rural employment guarantee scheme) and National Social Assistance Programme as well as increase budgetary allocation to improve poor households’ capacity to cope with the ongoing crisis.

Increasing the number of workdays available under MGNREGA to 150 days will reduce forced migration and thereby ensure that more children have access to parental care.

Save the Children-India conducted a study and modelling exercises to examine how access to social protection schemes (such as MGNREGA, PDS, pension, and others) contributes to improving a poor household’s capacity to afford nutritious food of their own choice. These models were developed from household level income and expenditure data collected in 2019 (pre COVID-19) when households also had other sources of income.

We found that when a household in the poorest quartile gets 100 days of work (the maximum number of days of work guaranteed annually as wage employment to a rural household) under the MGNREGA scheme, their capacity to afford a nutritious diet of their choice improves by 37 percent. Drawing on these findings, we conclude that increasing MGNREGA workdays for a household from 100 days annually to 150 days will not only increase employment opportunities in rural areas but also improve households’ capacity to afford a nutritious diet by 42 percent. Increasing the number of workdays available under MGNREGA to 150 days will also reduce forced migration and thereby ensure that more children have access to parental care.

Similarly, access to a widow or old-age pension scheme in an eligible household in the poorest quartile will improve their capacity to afford a nutritious diet of their choice by 17 percent. Here, we conclude that doubling benefits under the National Social Assistance Programme will improve an eligible family’s capacity to afford a nutritious diet of their choice by 25.3 percent.

Increasing the budgetary allocation and revising the design of these schemes will not only contribute to reducing household poverty but also address food and nutrition security for children, women, and adolescents; secure children’s education; and reduce the probability of children engaging in early marriage or any form of hazardous labour at a young age.

Dr Namrata Jaitli, Kamal Gaur, Prabhat Kumar, Radha Chellappa, Dr Antaryami Dash, Pranab Kumar Chanda, Manish Thakre, Sandeep Sharma, Shivani Bhaskar, and Sonal Rai contributed to this article.

Know more

- Read this comprehensive list of budget recommendations to secure children’s well-being.

- Explore these budget briefs that analyse trends in allocation and public expenditure of key social sector programmes.

- Read this perspective on the historical context of India’s budgets since Independence.

—

Footnotes:

- Cost of Universalising Early Childhood Education (unpublished), CBGA, 2022.