On June 31, 2021, in response to a petition on the struggles faced by migrant workers during the pandemic, the Supreme Court of India directed the central government to accelerate the process of building a database of unorganised workers. The government responded by launching the e-Shram portal—a national database of unorganised workers—in August 2021.

The idea of e-Shram is laudable in what it aims to achieve. There is no comprehensive database in India that provides information on workers across the length and breadth of the informal sector. E-Shram, however, takes into account a worker’s name, occupation, address, educational qualifications, skill types, and family details. It includes construction workers, domestic workers, street vendors, beauticians, waiters, rickshaw drivers, among others who are often unable to access the benefits of government schemes and policies.

The government has invested in nationwide awareness campaigns on e-Shram registration with banners, advertisements, and coordination through nonprofit partners working on the ground. According to news reports, by the end of November 2021, 91 million of the expected 380 million workers in the unorganised sector had already registered with the portal. However, these are just numbers. The ground reality is that e-Shram registration is an arduous process, and there is a considerable amount of apprehension and confusion among workers about its eventual benefits.

Who can register?

1. A worker with a mobile phone, an Aadhaar card, and a bank account

An Aadhaar-linked mobile number is a necessity for self-registration on the e-Shram portal. This in itself is a challenge for migrant workers who by the very nature of their work often move from one place to another and from one SIM card to the next. Ramendra Kumar, founding member of Delhi Shramik Sangathan—a federation of unorganised sector workers’ unions in Delhi—says, “Migrant workers do not treat their mobile numbers as permanent. They change numbers for many reasons—they might go back to their village and start using another SIM card, their phone might get stolen, or they might find out that Jio works better in a certain area they have moved to for work and throw away their Vodafone SIM.”

If a worker does not have an Aadhaar-linked mobile phone, they have to get it relinked to their current mobile number at the Sub-Divisional Magistrate office using biometric authentication which has its own challenges. Kumar says, “There is a long queue, and only 60 workers can get it done in a day. The other way is to go to common service centres.”

There are also cases where multiple workers living in a shared space use the same mobile phone. The government currently allows three people to register with the same mobile number.

Then comes the problem with bank accounts. To register on the portal, a worker must have an active bank account linked to their Aadhaar. With the push for the Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana by the government in recent years, while many workers have bank accounts, a large number of these lie dormant.

In other cases, their bank account might not be linked to their Aadhaar. Kedar Annam, who leads the e-Shram registration drive in Mumbai for Haqdarshak, an organisation that leverages technology to connect citizens to government welfare schemes, adds, “People often don’t have individual bank accounts, they have joint accounts. So, if a worker makes an e-Shram card with a joint account number, and then we try to make another card with the same number for his wife, the system doesn’t catch it.”

2. A young, digitally literate worker

Sheela, a domestic worker living in Sarita Vihar, Delhi, wants to get her e-Shram card made because she has heard from fellow workers that it might lead to monetary relief. The money is particularly important for her now because she was fired from work during the pandemic due to old age.

However, age is the very reason Sheela cannot get herself registered. She is 60, and only people from 16 to 59 years of age are eligible for e-Shram.

People in low-income groups working in the informal sector do not have the luxury of retirement, which the policymakers seem to have missed.

Harshita Sinha, a Phd candidate at London School of Economics who is currently researching migrant workers in the informal economy in India, says, “A lot of people will get excluded because in the informal sector many people are working beyond the age limit of 60.” People in low-income groups working in the informal sector do not have the luxury of retirement, which the policymakers seem to have missed. Annam adds another caveat. “There are times when the date of birth on a worker’s Aadhaar card is incorrect. So, regardless of their actual age, due to documentation issues, they may not be able to enroll on the e-Shram portal.”

What’s interesting to observe are the trends that are visible among workers who are getting their e-Shram registrations done with little to no trouble. Annam says, “Young workers who are part of collectives and unions have Aadhaar-linked mobile numbers. Those above the age of 35 are finding it difficult.” Kumar concurs, “Workers who have some formal education and digital literacy are struggling less.”

3. A worker who may not be from the unorganised sector

Even though e-Shram has been conceptualised as a database for the unorganised working population, there is confusion regarding who can register for the card. Annam says, “One of the major concerns is categorisation on the portal. Since exact categories for some occupations aren’t mentioned, we have to depend on workarounds. For example, we do not know where to fit someone who works as a helper at a construction site. There is a general ‘helper’ category but only for garment workers in the textile sector. For helpers in the sanitation, construction, and automobile segments, the helper category does not exist. When people cannot find their occupation listed, they just put in ‘helper’.” He adds that people in the unorganised sector often work double jobs and because the portal doesn’t recognise secondary occupations, they end up selecting arbitrary options.

Sinha agrees that there may be a skewed representation of workers in categories which needs to be recognised, “People who are drivers, doing cleaning jobs in the society, or helping with housekeeping jobs in societies are registering under the domain of domestic work, so that slightly skews the representation. Another challenge is that some of the categories don’t necessarily translate well from Hindi to English. Say, on a construction site when you are doing masonry work, kaarigar kind of work, those are not categories that are available on the e-Shram portal.”

There are other problems too. Provident fund (PF) account holders cannot be registered on the e-Shram portal. However, distinguishing them is not an easy job. Sanjay Parmar, Associate Vice President, Operations, Haqdarshak, says, “There are two kinds of PF account holders: people working as permanent employees and those working on contracts. The second set of people work for three months here and six months there, so their PF account keeps changing. At times they are working at a place where their PF account was opened under the government mandate, but the employers never put money into the account. So we help them register for e-Shram. There is also confusion about people who once worked in the organised sector and had PF privileges but now don’t.” He adds, “At times people also lie. They have an active PF account but they deny it, and there’s no way to cross-check from the PF portal.”

What do the workers think?

Workers are apprehensive but hopeful. Umer Singh, a construction worker in Delhi’s Pashchim Vihar area, says, “I got myself registered because I heard that people are getting money in their accounts.” He is also getting his wife, who works as a domestic worker, registered. Pushpa, a domestic worker in Sarita Vihar, has registered with the same hope of getting money in her account because she knows someone who knows someone else who has received money in their account.

This confusion is largely due to the fact that, before the state elections, the Uttar Pradesh government transferred INR 1,000 each into the accounts of 1.5 crore workers registered on the portal. This also reflected in the bank accounts of migrant workers residing in adjoining states such as Delhi, creating a false hope among the local community.

A digital product such as e-Shram doesn’t sit well with the workers. Unlike the PAN or Aadhaar card, the e-Shram ‘card’ is a soft copy.

However, many workers are still being cautious. Sinha says, “I have heard workers say, ‘You are collecting data from us; will we be in trouble because of this? Will we lose money? What will we get?’” Adding fuel to the fire, these fears have led to rumours that some people who registered on the portal have lost their money.

There is also the fact that a digital product such as e-Shram doesn’t sit well with the workers. The e-Shram ‘card’ is a soft copy. When one registers, they may not get a physical card in hand. “The card comes as a PDF, and people don’t necessarily understand its value. We have to print it out and give it to them so that they feel they’ve got something,” says Annam.

The lack of clarity from the central government on the benefits of e-Shram doesn’t help. Mohammad Asad, who is part of the Telangana operations of Jan Sahas, a nonprofit that works on protection of the rights of marginalised workers, says, “We are telling people that the only benefit as of now is that of insurance with the Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana where one gets a cover of INR 2 lakh in case of an accident and INR 1 lakh in case of any disability caused due to the accident. But the community perceives that more benefits will flow through e-Shram in future.” Everything else listed on the portal are existing schemes—such as Jeevan Jyoti Yojana or Ayushman Bharat Yojana—and to avail those, one will have to apply on each scheme’s portal separately.

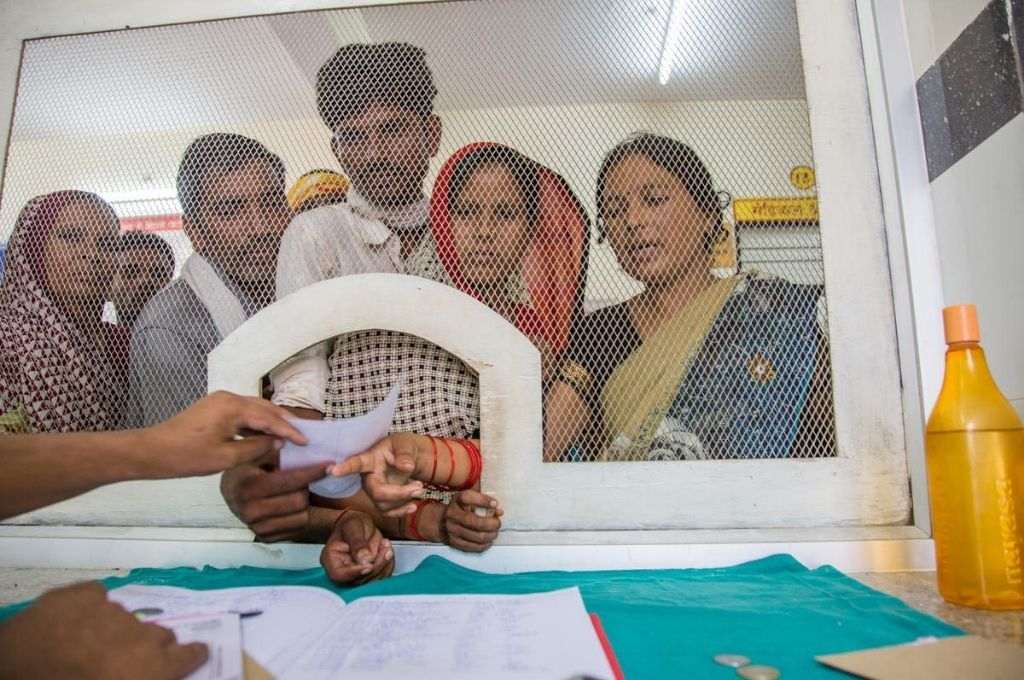

But there’s no denying the popularity of e-Shram. Despite the complications, workers are crowding camps and seva kendras to register on the portal. Garima Sahni, social security lead at Jan Sahas’ Migrants Resilience Collaborative, says, “We might wonder why people are queuing up for a card that just promises an insurance. But we are talking about people who have struggled their entire lives for pension and haven’t received it, or made multiple rounds of government offices for a BOCW card and haven’t got it. If the government is giving them a card without having to show a work certificate, an address proof, and a thousand other documents, they will take it.”

This article was updated on May 4, 2022 to state that workers may or may not receive printed copies of e-Shram cards at all centres.

—

Know more

- Read why e-Shram portal should provide desegregated data on migrant workers.

- Understand why the benefits of e-Shram registration remain unclear.

- Learn about the barriers workers face in accessing the e-Shram portal.