Around the world, one in two people live in an urban area. And, between now and 2050, three countries—India, China, and Nigeria—are expected to account for 35 percent of the growth in the world’s urban population, with India adding the most to this, a projected 416 million urban dwellers.

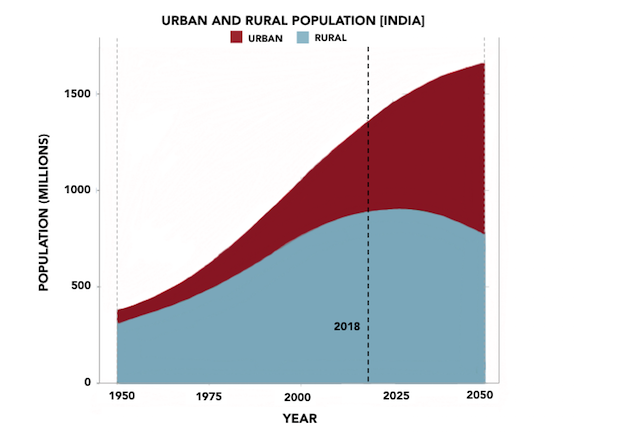

These are important trends because urbanisation, especially in the context of India, is leading to the growth of new, smaller, cities. These can bring in their wake more opportunities for higher incomes, better living conditions, and possibly lower carbon footprints. It is entirely possible that in the coming years, urban populations will overtake those living in rural areas, including in developing countries. However, urban areas, because of their dense residential designs are very dependent on public infrastructure to function well, including, in particular, the mechanisms for the management of human faecal waste. A great deal remains to be done on this front in most parts of the developing world and India.

Many Indian cities today suffer from over-crowding and low resources. In urban areas, infrastructure is not able to keep up with the rapid growth in population, and the influx of migrants. This is especially true in low-income settlements, where growth is often unplanned.

Sanitation issues in Indian cities and solutions:

Today, it is estimated that 78% of human faecal waste that is generated in India goes untreated into the environment. We, like most of the developing world, rely heavily on on-site sanitation containment (septic tanks and pit latrines). This is true for all small cities as well as for parts of large metropolitan cities. These areas require decentralised, non-sewered solutions for treatment and disposal, which are both sustainable and appropriate.

Faecal waste must be treated and disposed of safely, through effective faecal sludge management (FSM) which will, in turn, accrue both public health and environmental benefits. To deliver on this, we need change at multiple levels, including central, state and city governments, the private sector, and citizen engagement.

An enabling environment for sanitation work in India

India passed the National Policy on Faecal Sludge and Septage Management (FSSM) in February 2017, making it one of the first nations globally to have done so. The policy highlights government commitment to making safe and sustainable sanitation for everyone a priority area.

Related article: World Toilet Day 2017: Six ideas for sanitation

Since the passing of this policy, states across India have taken swift and concrete steps towards improving FSM. For instance, five states have already committed to funding the construction and operation of more than 400 faecal sludge treatment plants (FSTPs) across the country; another 11 have passed their own state-level FSSM policies; and several others are currently in the process of drafting theirs.

In order to sustain the attention and focus on sanitation, the government has initiated a ranking survey, Swachh Survekshan—an annual exercise that assesses and ranks cities on cleanliness and implementation of SBM initiatives. Today, this includes FSM-related indicators and assigns them weightage.

This tool is proving to be a strong impetus for city administrations to assess their performance on sanitation on the one hand, and attract greater citizen attention on the other. With the new indicators on FSM, there is already momentum among city and state governments to initiate interventions based on best practices of their peers.

Given the enabling policy environment for sanitation work, we now need a greater focus on building the capacity of institutions—both governmental and non-governmental—to deliver quality sanitation services, at scale and for the long-term.

Towards building long-term solutions at scale

The two primary challenges that we observe through our efforts at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation are related to the implementation of FSM solutions and limited stakeholder capacity. First, a steady supply of quality private sector operators—construction companies, consultants, experts—is needed to provide solutions and services.

Related article: Why cookie cutter models don’t work in development

Second, the capacity of cities themselves needs to be developed, so that they are well-equipped to manage the delivery of services around the infrastructure that is being built. City administrations need capacity building on FSM, and additional human, technical, and financial resources to match the growing demand. Therefore, in addition to working with states to prioritize FSM, both private sector stakeholders and municipal administrations must be engaged.

[quote]Effective faecal sludge management needs to be a key focus as part of the sustainability of all the sanitation investment the country has made.[/quote]Working in collaboration with our grantees, the foundation provides a range of support to government partners at state and city level. The support helps to make improvements along the sanitation value chain, through training and building the capacity of stakeholders—municipal workers, desludging operators, builders, contractors, and masons. They also work to address specific gaps, from fostering private sector involvement in FSM innovations, developing strong monitoring frameworks to deliver quality and equitable sanitation services, and supporting behaviour change communication.

Effective faecal sludge management is a core public health issue and needs to be a key focus as part of the sustainability of all the sanitation investment the country has made, particularly over the last four years. There is already a strong policy framework that the government has created and rising urgency among governments on the need to innovate and scale available solutions. It is encouraging to see states and cities stepping up to the challenge and committing resources—human and financial—to address the problem. What is needed now is quality implementation and engagement of private sector players, and the community’s awareness to understand its own role in ensuring safe and sustainable sanitation.