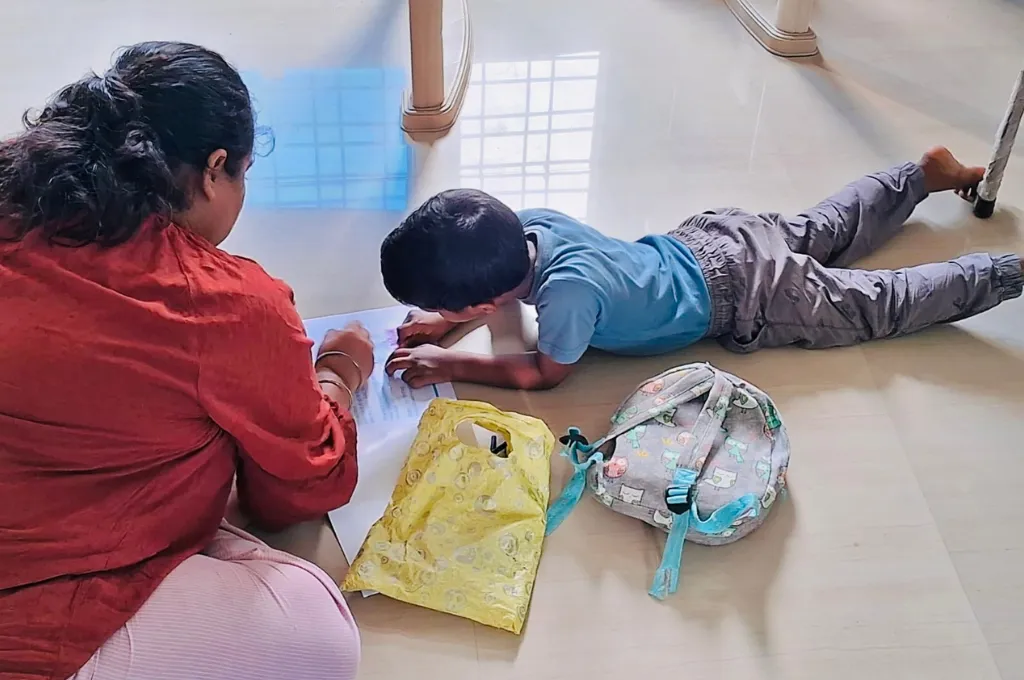

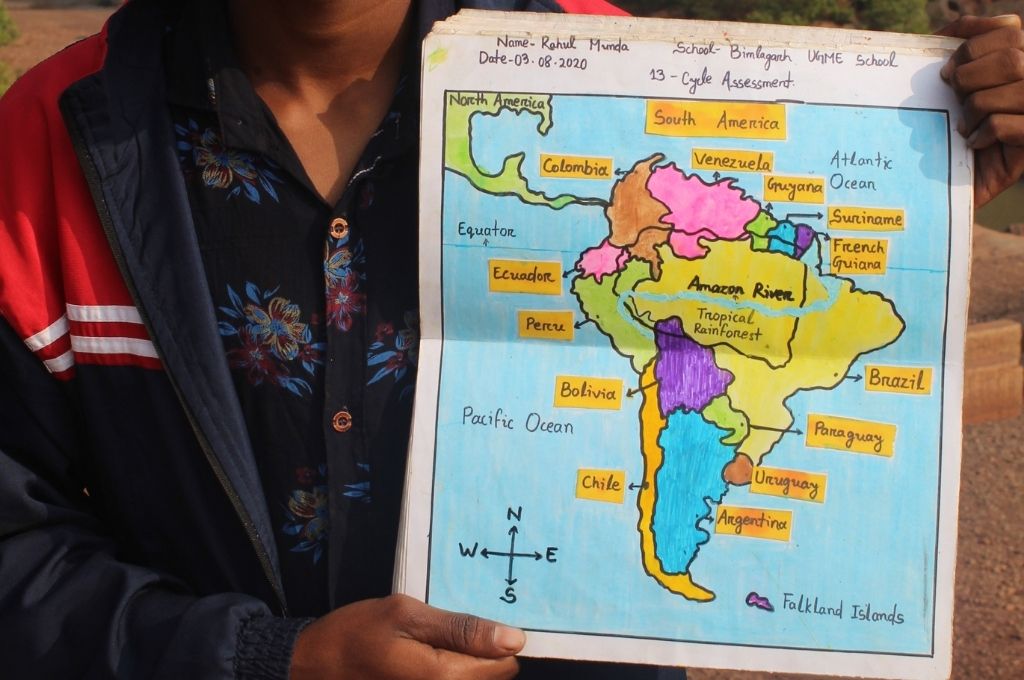

Rahul Munda, a Grade 8 student, from Kalo Sarai, a tiny Adivasi hamlet in Koira, sits in his small mud-brick house during the lockdown and draws maps of continents of the world. Koira is a remote iron ore mining region in the Sundargarh district of Odisha that bears out the adage ‘wealth below the ground and poverty above’. Rahul doesn’t have a smartphone, but he still uses the internet to learn about the world. This is because his teacher Seema visits him twice a week at home and helps him with his internet search on her phone.

Rahul is one of the 38 students spread across four hamlets, who Seema has visited at home during the lockdown. She takes specially designed learning tasks to them on her phone. Rahul says he finds the wide variety of learning tasks so engaging that he prioritises them over his football.

For Seema, this is a very different model of teaching. Prior to the lockdown, she used to work with the Learning Enrichment Programme (LEP)—part of the 1000 Schools Project run by Tata Steel Foundation and ASPIRE, where she taught children, largely first generation learners, after school hours to help them overcome their learning deficit. These schools were in areas that were serviced by a languishing public school system.

The lockdown forced a change in the model

Post lockdown, the programme had to explore how the 600-odd LEP teachers could stay engaged with almost 35,000 children of primary and upper-primary grades, who were now in their homes, spread across 2,653 remote villages, in a region that has just 14 percent internet coverage. This forced pivoting of the model led to:

- Redesigning of learning tasks to spark the interest of a child sitting at home, and drawing upon resources in and around their homes as well as the internet

- Teachers visiting the children at their homes every week and supporting them through the above tasks

- Assessing the children’s work and incorporating it as an input for the next week’s learning cycle.

Having done this since May, post lockdown, here are some things we learnt that might be helpful to other organisations facing the challenge of ensuring learning for children who are on the wrong side of the digital divide.

1. Children are natural learners and can learn in different environments

When the schools shut, LEP teachers, armed with smartphones, visited the children in their villages. They were given diverse learning tasks. Some incorporated elements of the children’s day-to day life, such as getting them to observe and write about plants, insects and birds in their surroundings, research agricultural processes and equipment used by their parents on their farms, make weather maps, and so on. Others helped expand their students’ horizons by getting them to learn the science and math of the COVID-19 virus from the Johns Hopkins’ website, and read about women achievers in their villages, states, and country.

Access to the internet coupled with the absence of formal teaching, classes, tests, and marks resulted in children exploring new, self-directed ways of learning. The result: More than 95 percent of the 35,000 children completed their tasks every week.

2. The internet is a strong enabler, but a teacher’s role is paramount

Pushing out content via screens is not enough. The teacher’s role is still critical, and they remain responsible for the learning of all the children in their class—whether in school, or even in an unprecedented situation like this, by teaching in their students’ homes.

3. Involvement of parents adds great value

Most of the children in the programme are first generation learners. Prior to the lockdown, their parents weren’t involved with their studies. But learning from home changed that. As children demonstrated progress, more than 100 parents bought smartphones to support their studies, despite their own jeopardised incomes. As a mother proudly said, “While others waste time on songs and games, my daughter uses the phone to gain knowledge.”

While the model helps provide insights into how children learn and how our schools and classrooms can be reconfigured and reorganised when normalcy returns, it was not without its challenges.

There were several challenges initially

The area that teachers had to cover each week varied from 3-4 hamlets up to 10-12 hamlets in remote areas. In many cases, the terrain was difficult to traverse, especially in hilly and forested areas. Teachers were expected to have two touch points with each child every week. In the initial days, children would run away when the teachers came. However, after repeated visits, the children became more receptive and settled into a rhythm with them.

There was also the problem of frequent panchayat lockdowns, as a result of which teachers were unable to either leave their villages or enter those that were under lockdown. In these cases, they mobilised local youth in the villages to serve as community teachers to the children.

Eventually these children became crusaders for COVID-19 safety protocols.

Many of these hamlets were also in internet-poor zones, and teachers would have to download videos or take print outs of learning material to show to the children.

Another challenge early on was adherence to COVID-19 safety protocols. As part of the process, teachers would upload pictures of the activities they were doing with the children. Oftentimes, pictures revealed kids sitting too close to each other, or without masks. It required repeated messaging at our end to ensure physical distancing and wearing of masks. But eventually these children became crusaders for COVID-19 safety protocols in their families and neighbourhoods.

We need more resources

Our initial survey in April 2020 had showed us that only 14 percent children had access to smartphones, and in 60 percent of the villages, children did not have access to a device. As a result, these children were completely dependent on the teachers’ phones to learn.

We are looking at ways to acquire more devices. If we can provide even one device per village, and keep it in the custody of the school management committee, it can be circulated among 10-15 children, allowing them a few hours of internet every week. This would enormously boost their learning.

With no visibility of schools restarting, especially the primary and upper-primary grades, we expanded the Lockdown Learning Programme at the end of 2020 to reach 1.36 lakh children, through 2,430 volunteer teachers in 4,510 villages of Odisha and Jharkhand.

—

Know more

- Read the ASER 2020 report to understand the status of rural education in India, during the lockdown.

- Read about how children learning during the pandemic surprised everyone in parts of Odisha and Jharkhand.

- Read about how the pandemic and efforts to maintain learning continuity may have worsened exclusionary trends worldwide.