“Government teachers aren’t interested in teaching.” This is a commonly held opinion in India.

However, the problem is not that teachers are simply not motivated, rather it is the training system that fails to respond to the contexts and challenges faced by teachers in their classrooms.

In many states of India, government-led teacher training is largely based on the cascade model, in which training is transferred down through multiple levels. While this approach can be scaled to reach a larger number of teachers, it often leads to ‘cascade loss’—a dilution of content and intent as the training moves from one level to the next. These trainings typically happen once or twice a year, are packed into four-to-five-day schedules, and tend to compress a large amount of content within a short time frame.

Moreover, these programmes are rarely tailored to the local realities of teachers. They often lack depth and are delivered in a one-size-fits-all format, with limited scope for peer interaction or collaborative learning. Follow-up support is minimal or absent, leaving teachers without any sustained academic inputs or feedback after the training ends.

Cluster-level meetings, which could have served as spaces for continuous professional engagement, are either overly structured with rigid agendas or irregular in implementation. Teachers seldom get opportunities for open academic discussions, reflection, and shared learning or problem-solving.

The current teacher training model highlights a pressing need to reimagine professional development by viewing it not as an event but as an ongoing, teacher-led process. Professional learning communities (PLCs) offer a promising alternative. They create a space for teachers with shared interests to come together regularly, reflect on their practice, and take ownership of their own learning journeys. Unlike one-off trainings, PLCs enable continuous, collective learning rooted in classroom realities.

A new approach to teacher learning

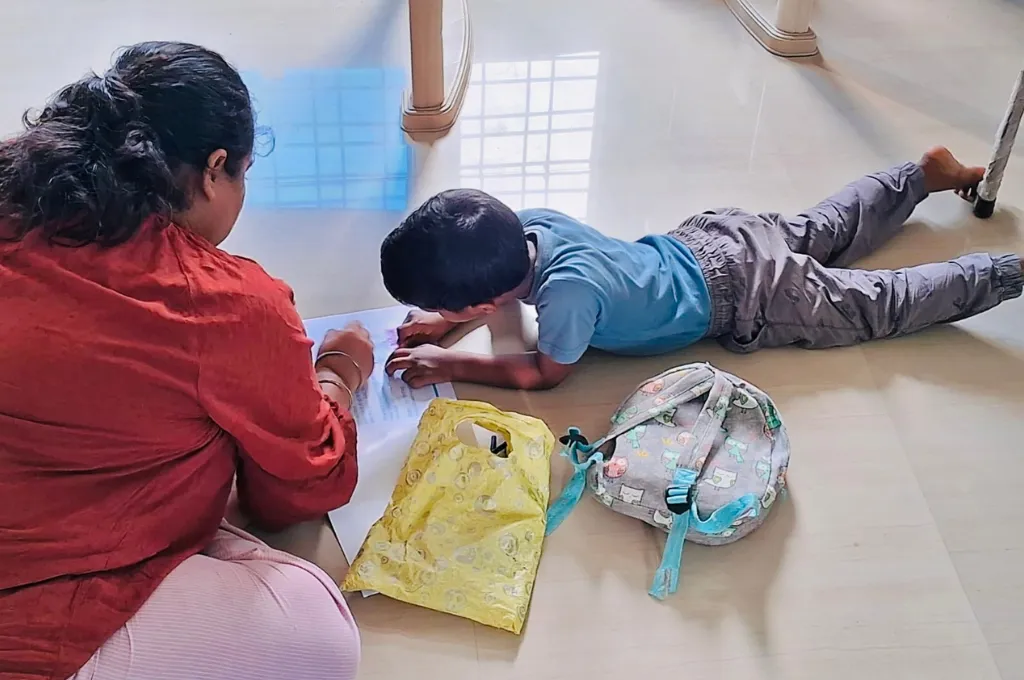

Let us travel to the district of Jaunpur in Uttar Pradesh (UP). It is mid-January, schools have just reopened, and a group of 57 primary schoolteachers have gathered after school hours. No government order, no official directive, just teachers coming together voluntarily.

Why?

To learn from each other, to address day-to-day classroom challenges, and to grow together.

Similar meetings are taking place across seven other districts in UP. This process is facilitated by a group of teachers, academic resource persons (ARPs), and state resource groups (SRGs)—all of whom are alumni of a year-long foundational literacy (FL) course offered by the Language and Learning Foundation (LLF).

In order to promote sustainable professional development of teachers, LLF placed emphasis on engaging alumni from previous programmes. While earlier we would hire external mentors, we began approaching alumni from the FL course and asked if they would mentor a new batch of learners. This would involve five to six hours of their time each week; they would have to select and enrol 10–15 teachers from their district in the FL course; organise weekly discussions; and, importantly, do it voluntarily, without financial compensation or official recognition.

Twenty-six teachers from eight districts agreed to participate and encouraged 350 primary schoolteachers to join the course.

This support network was built in response to the identified gaps in existing professional development programmes for teachers, including externally planned and top-down approaches, centralised courses, and inaccessible online modules. At a time when teachers are facing long-standing structural constraints, peer learning has helped address immediate needs in local contexts. Here are some reasons behind the success of this voluntary teacher model:

1. Teachers see opportunity and value in learning from one another

Instead of relying on external mentors, the more viable and scalable alternative is to identify and build the capacity of mentors and master trainers within the government system. These alumni—often highly motivated and committed—are willing to contribute beyond their regular working hours. For them, recognitions such as certificates, public appreciation, or opportunities to lead academic discussions act as strong motivators.

“I attend these meetings after school because they help me to enhance my knowledge and skills. The discussions have been very inspiring for me, and I have been able to learn new ideas and techniques as well as exchange useful information with my colleagues,” said Santosh Rao, a primary schoolteacher from Gorakhpur who has been part of this network.

This first batch of mentors were teachers with strong local networks and expertise in foundational literacy. For teachers enrolling in the course, however, there were still concerns regarding the time commitment. To address this, the alumni shared with them ways to balance learning with teaching and showed how the course had helped them in the classroom, including creating more interactive and engaging activities and simplifying difficult topics.

“We got to hear about each other’s experiences, which was one of the best ways to learn,” a mentor said. Another added, “If one teacher has been able to find a solution to a problem, it becomes immediately useful for the rest of us too.”

2. Teachers can relate to each other’s challenges

The one-year alumni extension model of the FL course is running in Gorakhpur, Jaunpur, Kaushambi, Mathura, Meerut, Varanasi, Shravasti, and Balrampur, with the last two featuring among the most economically vulnerable districts not just in the state but also in the country. These districts are spread across rural and semi-urban areas, comprising many children from communities where agricultural and daily wage labour are the dominant means of livelihoods.

Schools in these districts face structural challenges including lack of infrastructure and teaching resources, and heavy administrative workload. A shortage of teachers has also resulted in larger class sizes, with one teacher working with children from multiple age groups and grade levels, and even those who speak different languages. Teachers have also highlighted issues such as low levels of foundational literacy among students, high levels of absenteeism—especially among children whose families are engaged in migrant labour—and delays in the distribution of textbooks, all of which makes it difficult for children to retain what they have been taught.

Amid these challenges, teachers say that trainings are often only conducted once a year and feel more like a compliance exercise. Sessions tend to focus on sharing of information instead of offering practical strategies and meaningful professional development. Similarly, while the government’s Digital Infrastructure for Knowledge Sharing (DIKSHA) offers several courses, teachers struggle to navigate the portal and sometimes find it difficult to remember what they have learned. The alumni model has helped bring in a more hands-on approach, with discussions and suggestions for problem-solving that are relevant to classroom needs.

3. Teachers work together to resolve problems

The case for peer-led and contextual support is strong. Peer learning has helped address some of the issues mentioned above, as teachers from the same district or block are able to share similar experiences and come up with solutions that are directly applicable to their context.

For instance, teachers have now shifted their focus to oral language development in order to provide a strong base for reading and writing. Children are being encouraged to speak up in class, and learning is moving away from simply repeating or copying lessons from a blackboard. Decoding, or the use of letter-sound relationships to translate written words into speech, is also being taught in a more systematic manner and by using different learning materials to help children blend sounds and read words. Classroom learning is more interactive overall, with children working in groups and in pairs.

Sustaining a peer-driven programme

Given that teachers face heavy workloads and resource limitations, sustaining a peer-driven programme requires recognition, ongoing support, and meaningful engagement. Regular guidance and fresh inputs, including new teaching ideas and strategies to improve student involvement and learning, help keep the conversations engaging and relevant. Openness in discussion topics and allowing teachers to bring in real classroom challenges ensure that their participation directly benefits their daily work.

The peer-learning initiative has maintained flexibility in terms of coordinating discussion schedules and adjusting deadlines for assignments according to teachers’ needs, which reduces the pressure while ensuring that learning continues. Alumni mentors have also taken steps to secure in-person meeting spaces, including by contacting district authorities or holding discussions in informal venues.

Beyond academics, spaces for personal growth, motivation, and well-being can also make a difference. Teachers stay engaged when they feel supported not just as educators but also as individuals. Simple things such as peer encouragement, sharing success stories, and celebrating small milestones for progress help build a sense of achievement.

Most importantly, continuity in interactions is key. Regular check-ins, structured discussions, and problem-solving sessions help maintain momentum. When teachers see real improvements in their classrooms—whether through a strategy they learned or a child excelling because of their intervention—it builds their confidence and trust in the process, and they feel motivated not only to continue their own learning but also to be mentors to other teachers.

Strengthening peer learning through institutional support

Another way to boost motivation is through government recognition, which can be in non-monetary forms such as certificates, acknowledgement by officials, and opportunities to take on leadership roles.

PLCs, peer groups, and collaborative learning spaces can become powerful mechanisms to provide opportunities for growth and support to teachers that is both sustained and adaptable to their day-to-day needs. Moreover, since mentors are already part of the government system, leveraging their expertise while offering support through structures that recognise and enable their contributions can form a viable model for professional development and learning.

One active example of this is from Chhattisgarh, where the state government provided a group of such alumni a modest communication allowance of INR 500 for mentoring support during the implementation of a course designed by LLF. This model not only reduced dependence on external experts but also enhanced teacher ownership and embedded the practice within the government system itself.

A few other states have also seen some success in implementing peer learning, such as Karnataka through the Subject Teacher Forum. However, broader adoption of PLCs faces obstacles such as lack of policy integration, limited teacher awareness, and hierarchical school cultures.

Meanwhile, the importance of continuous teacher learning is acknowledged in policies including the NIPUN Bharat Mission. The National Education Policy 2020 also emphasises the need for continuous professional development and collaborative practices but does not explicitly mandate PLCs.

Several strategies can be adopted to strengthen PLCs and make them a core component of teacher development:

- Raising awareness about their potential for ongoing teacher-driven learning through campaigns or training.

- Providing government guidance on structuring PLCs, with mentors such as state resource group members to facilitate academic discussions on local school issues.

- Incentivising and recognising strong PLCs through certificates, forums, and integration into career progression.

- Encouraging contextual problem-solving by addressing specific challenges such as student attendance and support for migrant children.

- Creating platforms for PLCs to showcase best practices and share their learnings with others.

When teachers are able to collaborate in learning spaces, not only do they share ideas and provide support to one another but they also work together to resolve immediate and urgent problems. It can be an opportunity for teachers to feel motivated, to feel part of a community, and to be better equipped to meet their students’ needs—ultimately leading to confident and empowered teachers and more engaged classrooms.

—

Know more

- Learn more about the gaps in existing teacher training programmes and the recommended changes.

- Understand the importance of ensuring teachers’ well-being.

- Read this study on professional learning communities and how they can be operationalised.