According to the Reserve Bank of India, a conservative estimate of the total financing required for a successful green transition is approximately 5–6 percent of India’s annual GDP. However, the current contributions from public, private, and philanthropic capital fall significantly short of what India needs to meet its international climate obligations, or nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

While philanthropic capital alone is not sufficient, it can plug a critical gap in the funding landscape. Unlike traditional investments, philanthropic funding isn’t bound by the need for financial returns and can be deployed swiftly and flexibly, to back innovative solutions. With a greater appetite for risk, philanthropy can help fund initiatives that conventional investors might avoid and take a longer-term, more systemic view towards advancing climate action.

However, in India, data on fund flows towards climate action remains fragmented and inaccessible, hindering strategic and effective climate philanthropy. While there are annual efforts to track fund flows to key development sectors in India—including health, education, and livelihoods—mapping climate funding has not been institutionalised yet. This is largely due to the absence of clear, shared classifications for climate giving as well as a lack of transparency in funding strategies and priorities, all of which makes it difficult to map fund flows.

To develop a more nuanced understanding of India’s climate philanthropy landscape, the India Climate Collaborative (ICC) conducted a first-of-its-kind assessment based on data and observations from 2018 to 2023. Titled Trends in Climate Philanthropy, the study examined philanthropic fund flows towards climate outcomes in the country by:

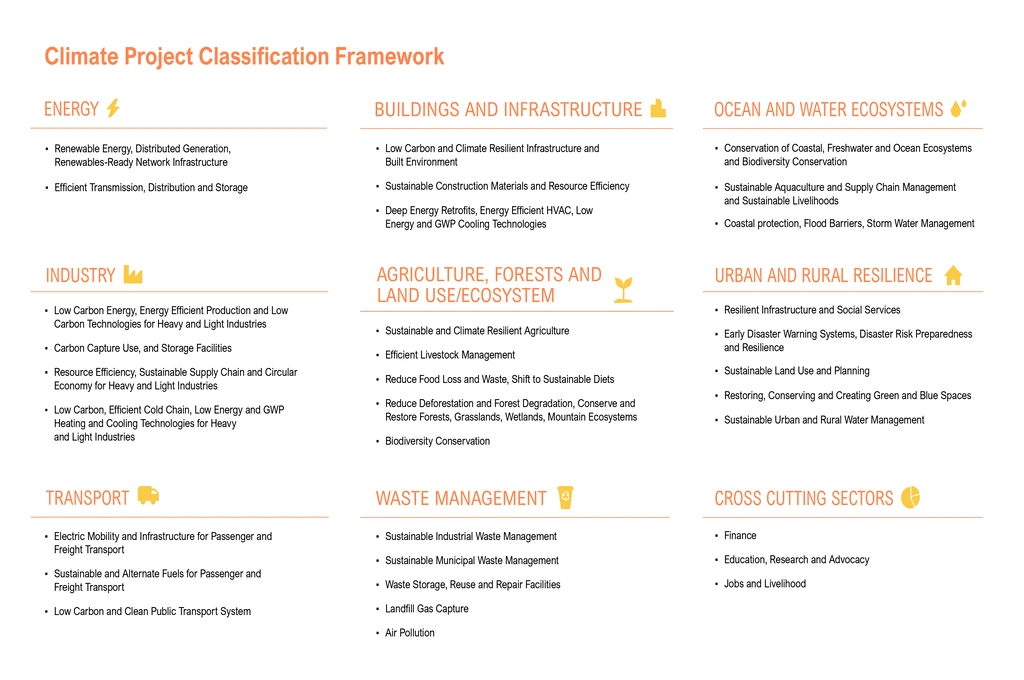

- Creating a project classification framework: While awaiting government-approved categorisations of climate finance, the ICC designed a new framework across sectors such as energy, transport, agriculture, forests and land use/ecosystem, and waste management. It also linked climate-related projects to key sectors and sub-sectors.

- Identifying levers of impact utilised by funders: As the climate crisis impacts a diverse array of sectors and geographies in India, funders use a range of approaches for grantmaking and project support. The study identified nine such levers of impact and analysed how funders are utilising them to tackle the climate crisis.

- Collecting and analysing data: Lastly, the study gathered publicly available data from 65 funders, including CSR funders, domestic and international foundations, and family offices. Gaps in the data were addressed through supplementary research where possible. Insights were bolstered with qualitative research, such as interviews and consultations with experts from key organisations involved in climate philanthropy.

This analysis has helped identify three ecosystem-level trends that are impeding the full potential of climate philanthropy in India:

Trend 1: Disproportionate focus on a subset of sectors

The assessment revealed that funders tended to focus on certain sectors and solutions that are more commonly as well as prominently associated with climate action. Areas such as clean energy (30.8 percent), agriculture, forests and land use/ecosystem (23.7 percent), and urban and rural resilience (17.6 percent) received most of the funding. However, sectors such as transport (3.9 percent), ocean and water ecosystems (1.6 percent), and industry (1.2 percent) received comparatively less funding, and buildings and infrastructure (0.6 percent) received the least.

The study also analysed which sub-sectors within each sector received more funding. For instance, within the energy sector, renewable energy and distributed generation received preference over efficient transmission, distribution, and storage. Similarly, in the urban and rural resilience sector, early disaster-warning systems, disaster risk preparedness and resilience, and restoration or conservation of green and blue spaces received maximum funding, whereas resilient infrastructure and social services as well as sustainable land use and planning received the least.

Trend 2: Utilisation of a limited number of levers of impact

To gain a deeper understanding of capital deployment across various sectors, the study examined the various levers used by funders. These include supporting organisations in daily operations, evidence building, capacity building, and raising awareness through communication strategies. The study also assessed the support provided by funders to grassroots organisations, marginalised groups, and development institutions undertaking on-ground implementation. Notably, three key levers for climate action accounted for 89 percent of the mapped capital: implementation support (62 percent), evidence building (15 percent), and capacity building (12 percent).

The study further found that some funders demonstrated agility in adapting their approaches to the specific needs of each sector. For instance, in the transport sector, two dominant levers were evidence building and capacity building. This reflects the early phases of electric vehicle (EV) adoption in Indian states over the past five or six years, as well as the roll-out of supporting policy frameworks during this period. The energy sector, which receives the bulk of funding across domains, appeared most focused on implementation—that is, moving funds towards the deployment of solutions for end users and testing out innovations in financing models instead of evidence building.

However, other funders displayed limited variation in approaches across sectors. Their preferences emphasise support for on-ground implementation of projects, with a concentration in sectors such as agriculture, forests and land use/ecosystem, urban and rural resilience, energy, and waste management. Other levers—for instance, capacity building, evidence building, communications and knowledge sharing, and core support—received little funding, with almost nothing for policy advocacy and innovative financing.

Additionally, most funders concentrated on using only a single lever, and this choice of lever was influenced by factors such as the maturity of the solution space or the funder’s previous approaches.

To effectively support a solution area, however, multiple levers across technology, policy, capacity building, etc. are necessary. While interviewing funders during the assessment, one suggestion that was echoed by most was the diversification of levers of impact in response to different sectors’ needs and maturity. Certain sectors, for instance energy, transport, and industry, offer a more immediate and discernible business case for investment given their alignment with economic growth and policy pushes towards decarbonisation. Within these sectors, philanthropists can identify sub-sectors and strategies that do not receive sufficient private or public finance while staying flexible. For example, over the last few decades, philanthropy has played a key role in catalysing the renewable energy ecosystem. This has been enabled by support for research and on-ground pilots as well as financial instruments such as risk guarantees and subsidies. While funders can continue to fund this sector, the solutions and levers of impact that need support will also need to evolve as the sector matures.

The study identified that the following levers can benefit most from philanthropic capital across sectors:

- Core support: In addition to supporting on-ground projects, funders can also invest in levers with a long-term lens, such as core support to bolster institutions, operations, and capacity building. For this, organisations need access to unrestricted, flexible capital over multiple years.

- Coalition building: Philanthropy can act as a binding force, bringing together diverse stakeholders—government authorities, technical partners, research organisations, and civil society—to build holistic solutions towards a common vision. This also ties into a growing consensus in the climate ecosystem: that no single actor can solve the crisis and that collective action is the way forward.

- Evidence building: This involves supporting academic, scientific, or empirical research; building knowledge products around nascent solutions; implementing innovative pilots where other funders are risk-averse; and developing scalable tools.

- Strategic communication: Funders and civil society are increasingly recognising the urgent need to invest in strategic communications for climate action. The study highlights that funders can prioritise developing an India-centric climate story that addresses national or subnational climate challenges and solutions. Additionally, they can play a pivotal role in making technical knowledge more accessible and easier to understand. This not only supports their own efforts to integrate climate considerations into their portfolios but also assists other stakeholders as they navigate the climate space.

The study also pointed to an emergence of a new category of funders— ‘next-gen philanthropists’. These philanthropists are highly conscious of the scale and urgency of India’s climate challenge, yet are undeterred by its complexity. They are willing to experiment with levers, capital, and sectors to find solutions that work. Their flexibility provides an opportunity to break traditional siloes for family offices and move beyond the need for returns, allowing the use of multiple financing instruments to ‘solve the problem’. This experimental mindset also opens doors for more collaboration and knowledge sharing with other types of funders, including more experienced philanthropists in the development sector as well as technical partners, civil society, and governments.

Trend 3: Geographical bias

Given India’s diverse topography, climate vulnerability can vary significantly. Many hotspot districts are increasingly susceptible to more than one disaster, aggravating uncertainties in forecasting and risk assessments. These vulnerabilities are further compounded by each community, state, or region’s development needs and access to finance at the state level.

However, the study found limited correlation between climate vulnerability and funding in India. Philanthropic capital flowed towards more ‘visible’ geographies in India, hindering climate action in other vulnerable regions. For example, according to a 2021 report by CEEW, India’s most vulnerable state is Assam, which is home to many of the country’s most vulnerable districts and where adaptive capacity is low. By comparing state-wise vulnerability indices to available state-wise fund flows, the ICC’s study found that Assam received less than 2 percent of the mapped CSR spending between 2018 and 2023. On the other hand, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and Uttar Pradesh accounted for approximately one-third of the total CSR spending. Other regions, such as Jammu and Kashmir, Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh, and Kerala, each received less than 1 percent of funding.

This could be due to several reasons. First, CSR funders tend to focus their grants on geographies where their head offices or key company operations, including factories, are located. Second, funders also often have lower visibility of the climate risks, urgency, and needs of geographies that are less accessible or have historically received lower funding. Third, civil society organisations that may be working in the more remote, climate-vulnerable regions may face challenges in accessing funding, especially if they are unable to speak the same language or communicate with funders in expected formats.

However, to ensure equitable funding across geographies—especially for the most vulnerable areas—funders can support access to granular data on regional climate vulnerabilities as well as fund flows by geography, helping to identify regions in need and backing local climate action plans. They can also enhance subnational capacity for climate action at the city and state levels through policy reform, technical assistance, and by bringing together key stakeholders. Additionally, investing in the capacity of civil society organisations in underserved areas—by strengthening communications and improving monitoring and evaluation (M&E) frameworks—will help track the climate impacts of projects.

The urgency of the climate crisis demands that India’s funders deploy capital swiftly, intelligently, and strategically across sectors and geographies, focusing on where it’s needed the most. They need to move from planning to action, whether by adopting a portfolio approach or applying a climate lens to sectors like livelihoods, education, and health. However, for funders to respond strategically and identify key areas for intervention, comprehensive and accessible data—at both macro and micro levels—will be critical. While this effort marks an important first step, there is a need for a more robust, ongoing commitment to collating and analysing data, as well as sharing it across the climate ecosystem. This will help highlight funding gaps and ensure that resources are effectively allocated to address the wide-ranging challenges of the climate crisis.

—

Know more

- Read the full assessment to learn more about the latest trends in India’s climate philanthropy ecosystem.

- Read this interview on why India’s climate philanthropy must adopt an equity lens.

- Learn how domestic philanthropies and nonprofits are stepping up for climate finance.