In a one-room home in Mumbai’s informal settlement of Govandi, nine-year-old Meena* prepares for school. She has already helped her mother with the morning chores such as filling water, sweeping, and mopping. She will spend the next six hours at school quietly copying from the blackboard and giving the ‘correct’ answers to her teachers’ questions. After school, more homework and tuition classes await her.

Hundreds of kilometres away, in a drought-prone village in Maharashtra’s Beed district, 12-year-old Sagar* returns to his local zilla parishad school after months of migrating with his parents to work in sugarcane fields far away from home. He looks forward to seeing his friends, but the classroom offers little joy. With only two teachers teaching five grades, lessons focus on keeping students busy.

Across India’s cities and villages, millions of children face overlapping barriers to learning, recreation, play, and childhood itself. This limits their ability to think independently, generate new ideas, ask questions, and explore the world around them.

Despite growing evidence and the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020’s acknowledgement of the importance of play-based pedagogy, play is kept at the fringes of our classrooms and schools, overlooking children’s well-being, agency, and future-readiness. Systemic barriers have made it difficult to integrate play in schools, with challenges including overcrowded classrooms, rote learning, overburdened teachers who find it hard to adopt play-based methods, and parents who equate learning with discipline and exam scores rather than creativity or individuality.

Why play is important

The Opentree Foundation uses play to strengthen the well-being, learning and holistic development of more than 2 lakh children from low-income communities and to implement Life Skills Play Programmes in over 600 schools in 12 districts of Maharashtra. Teachers had been raising concerns around behavioural issues such as aggression and poor learning motivation among students. We responded with a three-year study with 2,000 children to assess the impact of play-based practices on students and teachers.

In 2023-24, we launched our Play-based Life Skills Assessment Framework to push for child development to be seen as more than just learning outcomes. We found that integrating regular games within the classroom created safe, welcoming spaces for students to express their feelings and ask questions without fear. Gradually, students began to trust their teachers, bonding with them and becoming more responsive and participating in the classroom. Because playing comes naturally to children, it is an opportunity to observe each child’s individuality, agency. Teachers observed an increase in students’ curiosity, attention span, critical thinking, communication skills, and openness to sharing, which increased their propensity for learning.

Here’s how we helped incorporate play-based learning in public schools and navigated the obstacles along the way.

1. Rethinking the idea of play

The challenge lies in the misconceptions surrounding play. Teachers, principals, and community leaders often say, ‘‘Our schools have playgrounds; children play before and after school. Why do we need a programme just for children to play?” or “We have a sports period. Isn’t that the same?”

Perceptions shifted when they participated in play sessions and saw the improvement in children’s engagement.

The facilitators would invite teachers to join, demonstrating how games build collaboration, problem-solving skills, and independent thinking. They would share observations after each session and suggest simple activities that teachers could lead themselves. The teachers discovered that games such as solar system puzzles and alpha-numeric games aided their own teaching, while others like Mechanix (a mechanical construction game) develop skills such as imagination, spatial awareness, creativity, and critical thinking.

Conducting reflective workshops with teachers and principals helps further. During these sessions, teachers recall their childhood memories, explore how play fosters joy and connection, and discuss questions such as ‘What happens when the idea of play leaves our lives?’ and ‘Why must we protect our children’s right to play?’ They share classroom stories, discover new ways to use play in their own contexts, invent games and activities with their students, and co-create a play timetable for their schools.

2. Reducing the burden on teachers

Embedding play into classroom lessons doesn’t increase a teacher’s burden, rather we have seen that it does the opposite. Starting the school day with crossword puzzles and riddles encourages children to reach school on time. Sometimes, the children even lead these play experiences. In schools with teacher shortages, games help keep children engaged as teachers move from one class to the next.

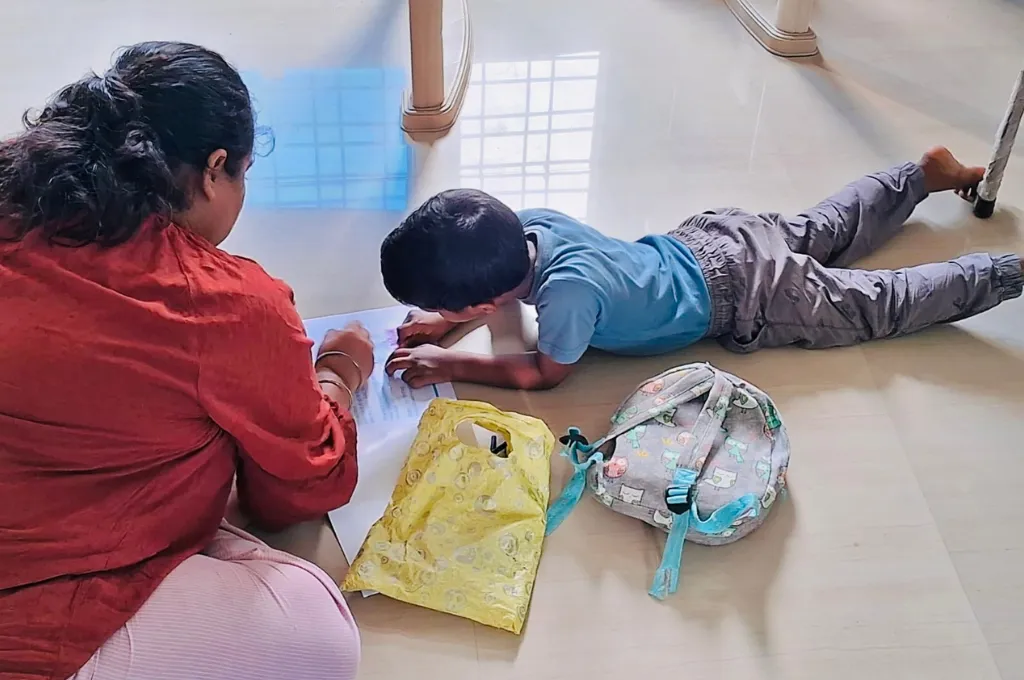

Our on-field teams support teachers through coaching visits, co-facilitated play sessions, and classroom observations. We also help schools integrate play into parent–teacher meetings and second Saturdays. For example, in rural Maharashtra, we leverage NEP-mandated daptar-mukt shanivaar (bag-free Saturdays) to organise longer play sessions. Some of our partner schools use report card days and parent–teacher meetings to conduct play sessions not just with children but also with parents.

For instance, in Sangroli village near Maharashtra’s Nanded district, mothers of the students hesitated to participate in parent–teacher meetings. To put them at ease and break the hierarchical structure of such meetings, teachers organised a puzzle competition that made the meetings more interactive.

3. Addressing children’s unique challenges

Play builds confidence, especially for children growing up in adversity and uncertainty. At a partner school in Mumbai, teachers and facilitators introduced Mechanix to a group of girls. Initially, the girls refused, as they felt the game was ‘meant for boys’. They gained confidence over time and learned to build different objects within the game, such as cars, planes, and trucks. Many girls developed an interest in using mechanical tools and, eventually, they assembled a bicycle from scrap parts.

These are some examples of how play can shifts mindsets inside and outside schools. Our experience of working with children from diverse backgrounds in Maharashtra shows that play is pivotal to children’s development and makes classroom learning more productive and engaging. However, a large-scale adoption of this approach will require policy backing and funding. For example, all anganwadi centres should be equipped with play libraries and materials. Similarly, the Union budget allocated to children’s welfare should have a clear mention of play. The situation won’t change unless play is recognised as a child’s right.

*Names changed to maintain confidentiality.

—

Know more

- Read this study to understand how play-based learning positively impacts employment potential.

- Read more about how to build inclusive schools.

Do more

- Become part of the discourse on play by attending the Play Summit 2025.