In the field of solid waste management (SWM), we often hear that ‘waste is wealth’—a notion that signifies a paradigm shift where waste is no longer viewed as a burden but as a resource that can be revitalised and reintegrated into the economy. At the heart of this idea lies the promise of the circular economy: to reframe waste as raw material with latent value.

While this rings true in urban or industrialised contexts where recycling ecosystems are mature and market linkages exist, it fails to resonate in remote, hilly geographies such as Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. In these areas, low-value waste is more prevalent, logistics are expensive, and informal recycling networks are fragile or absent. The result is a system that struggles to convert theory into practice.

There has been a lot of discussion around waste management in the Indian Himalayan Region (IHR). However, there are complex and unexamined challenges that affect the financial sustainability of rural waste management in the area. Having worked in this region for more than a decade, our data and observations reflect its unique reality.

The efficiency of SWM operations in the region is greatly hampered by its remote terrain, scattered populations, lack of resources, infrastructural deficiencies, and inadequate institutional support. These factors add to the multilayered complexities associated with waste recovery and value generation.

When discussing waste management systems, the conversations often focus on operational sustainability—who will manage it, how it will sustain itself, and what’s the best revenue model for it. However, a simpler and more foundational question needs to be answered first: Is it even possible to build such a system?

Building this system would require an upfront investment in land (which is scarcely available in the IHR), construction, equipment, and compliance-related expenses. What seems theoretically feasible does not work on the ground when the financial and logistical challenges are more diverse and complex than anticipated.

Therefore, to design a sustainable waste management system, the focus should be on a key pillar of sustainability—the economics. This involves identifying economic bottlenecks, and the lived realities underlying them.

The economics of rural waste management

The problem of solid waste in India’s rural and hilly regions is understood to be perpetuated by factors such as logistics, geography, socio-economic conditions, infrastructure, and seasonal tourism—all of which exert pressure on these fragile ecosystems.

However, in rural areas, the lack of reliable data on waste generation, management practices, and the associated financials—particularly around capital and operational costs—prevents informed policymaking and financial planning. This often leads to a sustainability shortfall, as funding remains irregular, and skewed towards infrastructure instead of day-to-day operations.

Our estimations suggest that approximately 8–10 kg of dry waste is generated per household every month. In densely populated areas, managing this volume of waste is not particularly challenging, as services can be delivered more efficiently due to shorter collection routes, shared infrastructure, and lower per capita costs.

However, in isolated or sparsely populated rural areas, the situation is markedly different. Collection becomes more logistically complex due to infrastructural limitations, and the cost per household increases significantly. For example, in our study area which covered 10 gram panchayats comprising approximately 5,000 households in Himachal Pradesh,1 the estimated end-to-end cost for waste collection, segregation, and transportation per month is approximately INR 80,000 per gram panchayat.

Approximately 26 percent of this cost can be recovered through user fee, while an additional 20 percent can be offset by the sale of recyclable materials. Under the Swachh Bharat Mission–Grameen (SBM–G) Phase II, only INR 16 lakh per block has been allocated for capital expenditure by the XV Finance Commission and Gram Panchayat Development Plan (GPDP) budgets—intended for setting up plastic waste management units and basic solid and liquid waste infrastructure. However, this allocation does not cover ongoing operational costs such as salaries, maintenance, or fuel. Coupled with the limited nature of the XV Finance Commission and GPDP grants, this capital-heavy funding structure poses a substantial barrier to establishing and sustaining waste systems in rural and hilly regions.

At Waste Warriors Society, we encountered this financial gap through our work supporting rural waste systems in Himachal Pradesh and Uttarakhand. While our waste workers are formally employed, and receive regular salaries through philanthropic funding, the broader system presents a different picture. In many other contexts, especially where operations rely on inconsistent government support, community-based or informal waste workers face livelihood insecurity due to delayed payments and a lack of sustainable funding structures. This makes it difficult to assess or ensure the long-term financial sustainability of rural waste systems.

While studying the economics of waste management systems, we also sought to understand whether the income generated from the sale of recyclables can cover operating costs. In most cases, the answer was no. And when revenue from these sales falls short, it limits the ability to pay fair wages, offer job security, or provide protective gear and training. In systems that aren’t subsidised through external support, this can lead to low morale among workers, high attrition rates, and unsafe working conditions. Over time, this worsens not just worker well-being, but also the consistency and quality of waste services themselves.

The approach: Financial Sustainability Index (FSI)

To drive transparency, scalability, and measurability in rural waste systems, we developed the Financial Sustainability Index—a data-driven tool that tracks how much of the operational cost is recovered through local and institutional income sources, including user fees, sale of recyclable waste (plastic, metal, paper, or glass), government support via institutional schemes, and interdepartmental convergence mechanisms.

This structure is scalable and adaptive to terrain, and helps uncover the real economics of waste-management operations, offering key insights to support policy, and strengthen local governance.

To address the economic question raised, insights were drawn using data collected from our study area, which comprises approximately 5,000 households—of which more than 2,000 were successfully onboarded to a weekly dry-waste management service. It explores the full value chain, starting from collection to processing and end disposal, by analysing the operational expenditure cost, revenue flow, and financial gaps. The FSI uses data from a dry-waste management system implemented over 12 months (April 2024 to March 2025) by Waste Warriors, through local entrepreneurs and the local panchayat.

What the data says

Over a period of 12 months, 265 metric tons of waste was collected from the study area. Yet only 46 percent of operational expenses—collection, processing, transport, fuel, facility rent, PPE, and staff salaries—was recovered through the revenue generated from this waste, resulting in a 54 percent operational deficit.

A closer look reveals the financial gap:

- Collection costs approximately INR 8.04 per kg, while income is INR 5.06 per kg—leaving a 37 percent deficit.

- Processing costs are approximately INR 11.57per kg, but income stands at only INR 3.92 per kg—creating a 66 percent deficit.

These gaps have real consequences for rural systems. Without sustained external support, funding shortfalls don’t just delay waste operations—they risk shutting them down entirely. In many cases, this also jeopardises the ability to fairly compensate workers or maintain consistent service delivery.

The financial struggle becomes real when we have a clear picture of what is being collected and what value it holds.

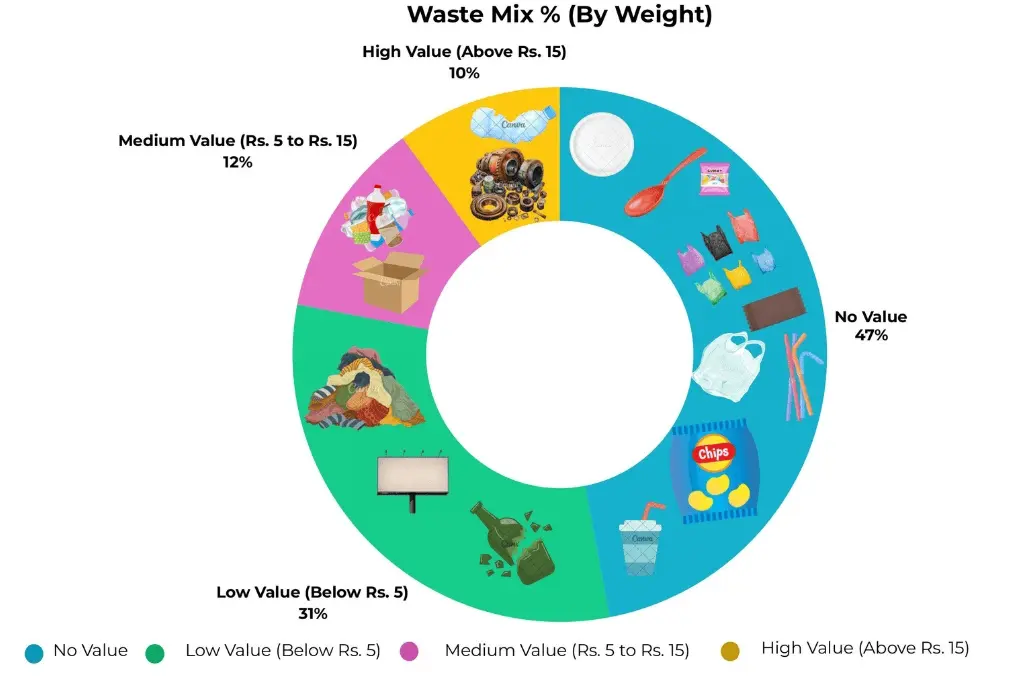

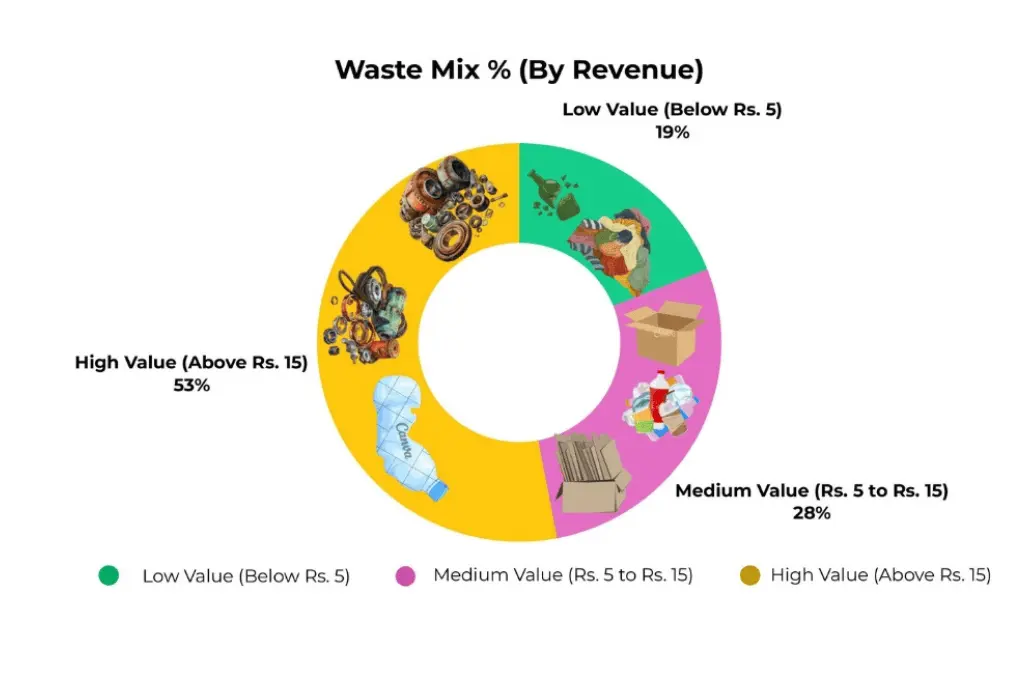

- Approximately 78 percent of the waste quantum is comprised of ‘no value’ and ‘low-value waste’ (sale price per kg below INR 5). However, such waste contributed to only 19 percent of revenue.

- Only 12 percent of waste was of ‘medium value’ (sale price per kg between INR 5 and 15) and generated 28 percent of revenue.

- Only 10 percent of the waste quantum consisted of ‘high value’ (sale price per kg above INR 15) waste. This generated 53 percent of the revenue, making it the financial backbone of the waste stream.

Conversations around financial sustainability generally focus on numbers related to cost, recovery, efficiency, and revenue. But these numbers are reliant on the material that enters the system. In such regions, we also often encounter a tightly knit, highly organised system of informal actors who operate in parallel with (and occasionally compete against) formal systems. These waste pickers and scrap dealers are remarkably efficient at collecting and buying recyclable waste, even from remote locations. As a result, the waste that eventually reaches formal systems has already been picked and sorted.

This upstream filtration reduces both the volume and value of waste left for formal systems to process—creating a financial challenge for nonprofit- or panchayat-led efforts. This dual structure affects the viability of formal systems and can further entrench informality.

To bridge this gap, a more integrated approach is needed. Formalising the role of informal networks—by offering them stable recognition, training, and incentives—could help secure their livelihoods while also strengthening the economic foundation of rural waste systems.

Waste does not equal wealth

At present, waste as a venture does not lead to profitability in certain geographies. Through our work over the years, one thing has become evident: Eradicating a socially pervasive environmental problem such as waste takes time. It involves negotiation, trust-building, and adaptation over a period of time. Both cost recovery and scale are limited due to sparse populations, small levels of waste, limited institutional capacities, and affordability constraints—even though the model might be very efficient.

And when systems remain underfunded, or collapse altogether, the burden falls squarely on local waste workers, volunteers, and community champions including local governance. Income instability, emotional burnout, and physical strain from working without proper equipment or safeguards become daily realities—undermining not just livelihoods, but also the sustainability of the system itself.

Social and economic challenges are interrelated and, in turn, make service delivery harder, and expensive. Social hurdles directly impact the economy of the waste management system. Mistrust, cultural beliefs, caste, and many taboos around waste-handling further add multiple layers to resistance or unwillingness.

The factors that limit the efficiency of waste management can be addressed by incorporating large infrastructure, long-term commitment, and viable financial models. It takes years for financial stability to be established. But during this time, philanthropy can play a significant catalytic role. It can offer initial investments that support operational expenditure—filling financial gaps till the locally rooted model can stand on its own.

In addition to this, multiple corrective measures will be needed over the long term. These include:

1. Strengthening extended producer responsibility (EPR)

At present, EPR covers only a fraction of costs in the Himalayas. For low-value plastic (LVP), companies offer approximately INR 1 per kg as additional revenue. But in hilly terrain, transporting this waste costs INR 3–4 per kg—wiping out the benefit. A more geographically sensitive EPR mechanism is thus needed. For example, cement factories and other industries that use LVP as fuel could be mandated to also cover transportation costs. Planning EPR at a district or sub-regional level would allow waste to be aggregated across gram panchayats, creating economies of scale. In addition, aligning infrastructure with segregation at source—for instance, renaming panchayat-level waste management units as material recovery facilities (MRFs) focused on dry waste—would make the system more effective. Finally, involving the forest and tourism departments in waste management committees could ensure convergence, while earmarking land for MRFs at tourist sites would build long-term capacity.

2. Covering operational costs under Swachh Bharat Mission–Grameen 3.0

Current guidelines prioritise capital expenditure—such as setting up infrastructure—but neglect recurring costs such as wages, fuel, transport, and maintenance. Without this support, the infrastructure risks falling into disuse. Hilly areas also face unique construction expenses: site levelling, retaining walls, and smaller land parcels result in costs far higher than the current provision of INR 16 lakh per block. Revised norms that reflect this reality are needed. Sub-block level facilities, which are more practical in dispersed geographies, should also be allowed.

3. Using Gram Panchayat Development Plan (GPDP) funds for day-to-day operations

GPDP funds are usually earmarked for one-time infrastructure, but they could also support recurring costs such as collection and transportation. A dedicated operational expenditure component under the SBM–G, with a mandated line item for solid waste management, would give gram panchayats a predictable resource stream. Tourist-heavy districts could explore local fee-based models, such as adding a waste-management charge to entry tickets, hotel bills, or parking fees. Assam’s rural development department already provides a useful precedent: Gram panchayats there pay INR 15,000 per month to self-help groups or nonprofits for waste collection and processing. This predictable payment model could be replicated in other states.

—

Footnotes

- The study area consisted of six gram panchayats in Dharamshala (Baghni, Barwala, Narwana Khas, Rakkar, Sokani Da Kot, and Tang Narwana) and four in Baijnath (Bir Khas, Chaugan, Gunehar, and Keori).

—

Know more

- Learn more about the status of solid waste management in the Indian Himalayan Region.

- Learn why the Himalayas are drowning in waste.