Women have emerged as the single largest category of persons disproportionately impacted by COVID-19. The female labour force in January 2022 is 9.4% smaller than it was in January 2020 even though the male workforce returned to pre-pandemic levels in June 2021, show latest data. Through the surges, women carried the burden of increased unpaid work—childcare as schools remain closed and elder care as the health infrastructure crumbled. Also, formal complaints of domestic violence more than doubled between 2019 and 2021.

In a crisis such as this, gender responsive budgeting (GRB) can be an effective instrument to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment through fiscal policy. Gender budgeting requires the earmarking of government expenditure against targets to incentivise gender-sensitive actions.

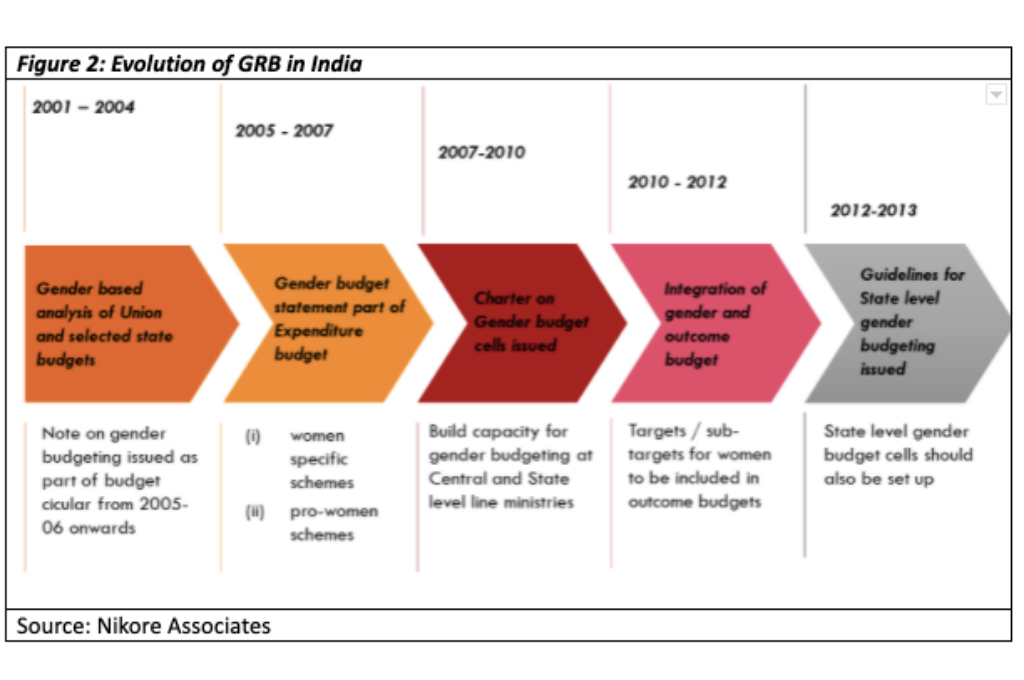

Evolution of gender budgeting in India

Today, India counts among the over 90 countries practicing gender responsive budgeting. India has been consistently releasing a Gender Budget Statement (GBS) along with its Union Budget since 2005–06, and it has been recognised as one of the most streamlined and detailed gender-responsive budgeting documents in Asia. Released as Statement 13 of the Expenditure Profile, it presents the portion of budgetary expenditure earmarked by Central ministries to alleviate gender-specific barriers across schemes.

A charter issued in 2007 mandated the formation of gender budget cells across ministries for this kind of budgeting, and currently these exist across 57 Central ministries and 16 state governments. The Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) developed a comprehensive Gender Budgeting Handbook in 2015.

Still at 1% of India’s GDP

Analysing the FY23 Gender Budget against its 16 predecessors shows that this Budget continued several existing trends and introduced a few new elements. We enumerate these trends:

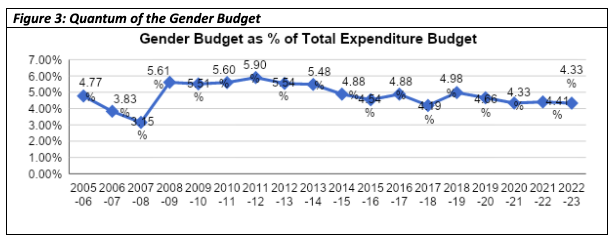

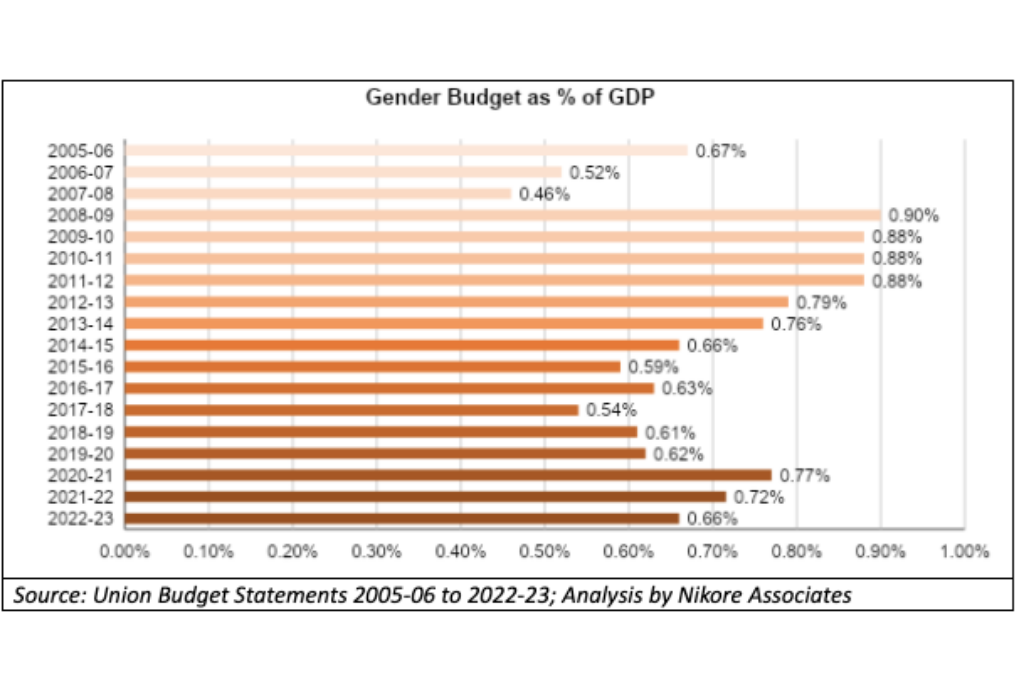

1. In line with the pattern of the last 16 years, it remains below 5% of total expenditure and at 1% of India’s GDP

The overall size of the Gender Budget grew from Rs 1.66 lakh crore in FY22 to Rs 1.71 lakh crore in FY23, an increase of only about 3% compared to the 4.6% hike seen in the overall government expenditure. Despite this increase, the Gender Budget has actually declined as a proportion of the total expenditure—from 4.4% in FY22 to 4.3% in FY23—and also when compared to the GDP—from 0.72% to 0.66%. An analysis of the data between 2005–06 and 2021–22 reveals that the Gender Budget has hardly ever crossed 5% of total expenditure or 1% of GDP.

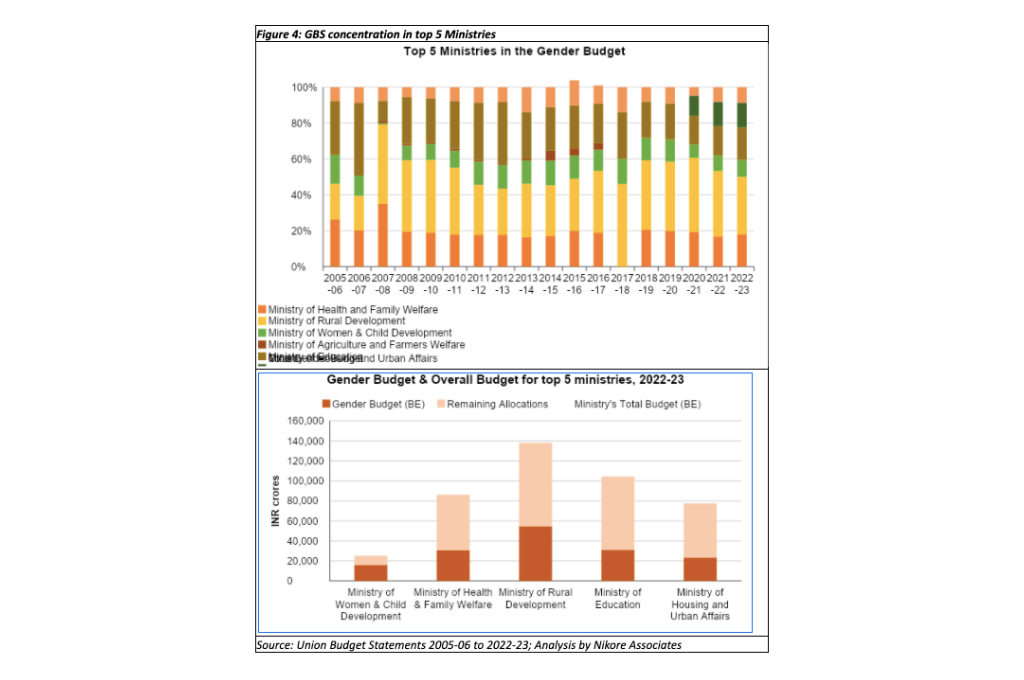

2. About 90% of the gender budget allocations remain concentrated in five ministries, with just over half even reporting allocations to it

In FY23, allocations to just five ministries comprised 91.3% of the gender budget statement—rural development, women and child development (WCD), housing and urban affairs, health and family welfare and education. Only 40 of the over 70 central ministries and departments even reported gender budgeting in FY23, as per the GBS.

This trend is not new: between 2005–06 and 2019–20, almost 90% of the Gender Budget was focussed on rural development, WCD, agriculture, health and education. Since FY22, the increase in allocations for the Prime Minister Awas Yojana (Urban) resulted in the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs superseding the Ministry of Agriculture in the top five ministries.

With the exception of the MWCD, which delineates 64% of its overall budget as Gender Budget, only 30–40% of each ministry’s overall expenditure can be counted as gender-centric allocations.

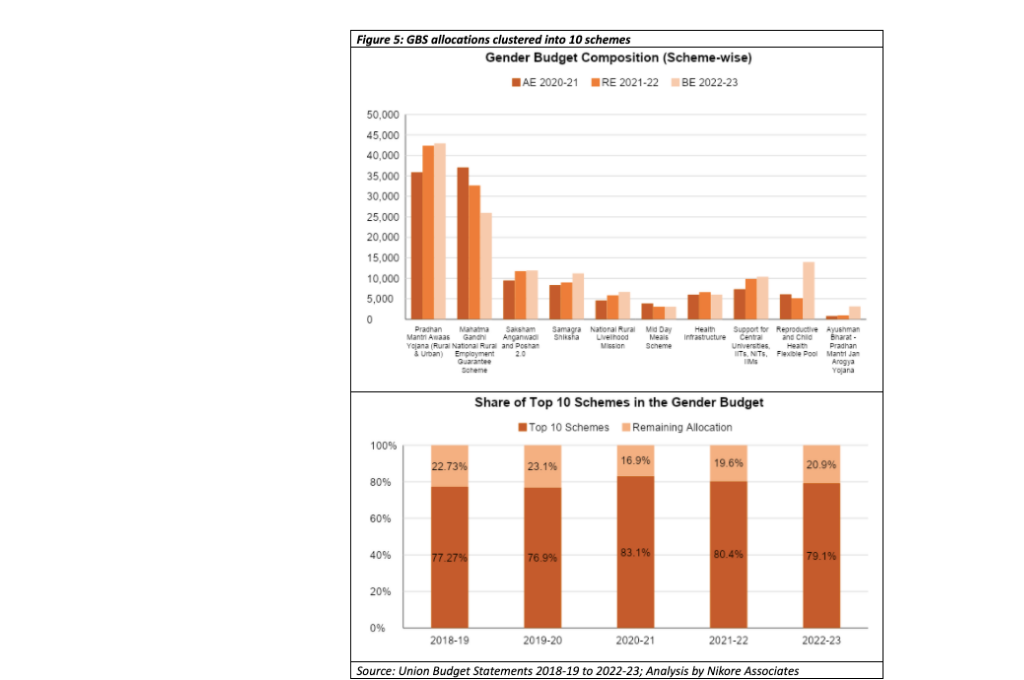

3. About 80% of the FY23 GBS allocations are clustered into just 10 schemes

The PMAY (Rural and Urban) and Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS) alone form 25.1% and 15.2% of the FY23 GBS. The top 10 schemes constitute almost 80% of the allocations in FY23, a decline over the last two years—the figure was about 81-83% for FY21–22.

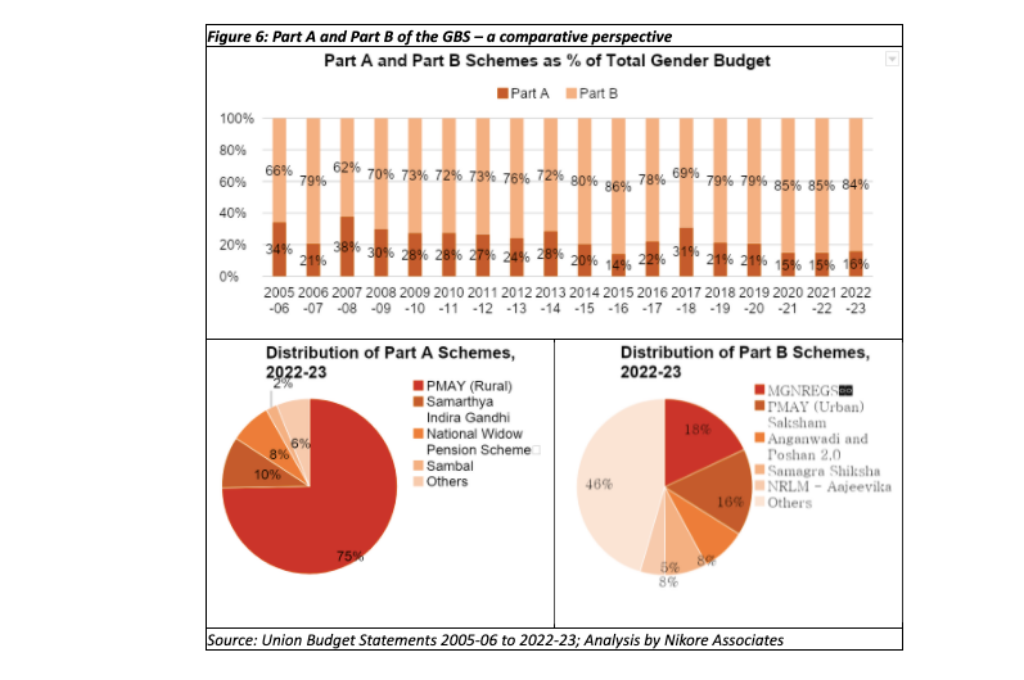

4. Allocations in 100% women-focussed schemes have declined

There are two kinds of allocations in gender budgeting in India: Part A comprises women-specific schemes (100% allocation for women), and Part B for pro-women schemes (30–99% allocation for women). While allocations for the Gender Budget are dominated by schemes in Part B, this skew has worsened in the last five years with the proportion of schemes in Part A declining from 31% in FY18 to 16% in FY23.

Major schemes in Part A of the FY23 Gender Budget include the PMAY (Rural), the Samarthya scheme (MWCD’s umbrella programme on women’s welfare) and the Indira Gandhi National Widow Pension Scheme. The Ministry of Rural Development, along with the MWCD, are the highest contributors to women-specific schemes. Part B of the Gender Budget has a wider distribution, with PMAY (Urban), MGNREGS, Saksham Anganwadi and Poshan 2.0 and Samagra Shiksha being the major schemes.

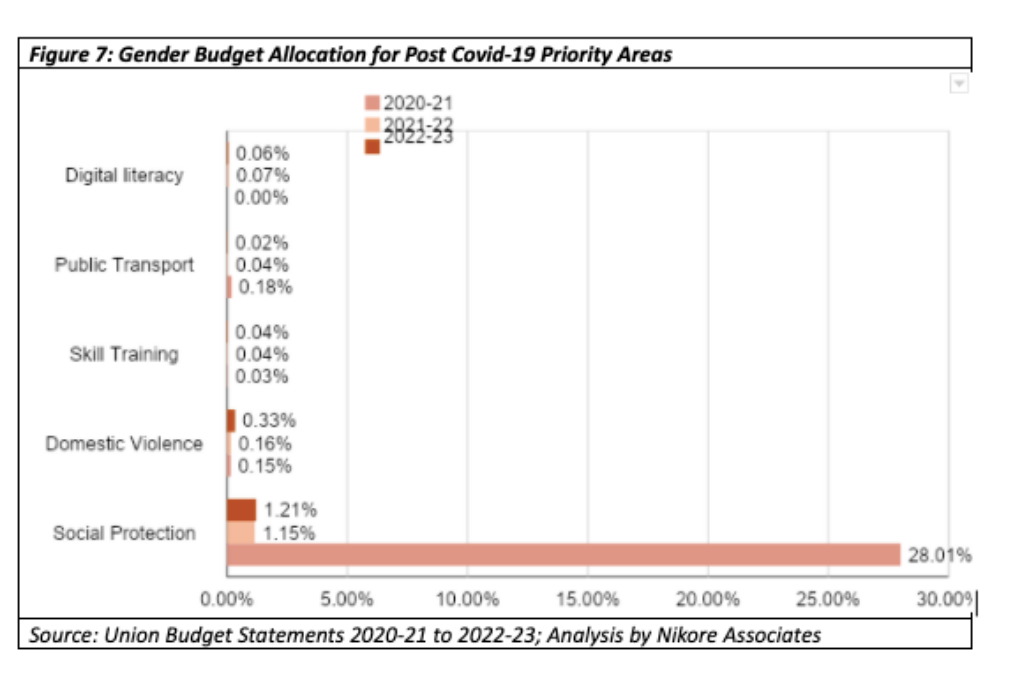

5. Not responsive to emerging post COVID-19 priorities

Expenditures on five post-COVID-19 priority areas—social protection, (including income support, food and fuel transfers), prevention of domestic violence, skill training, public transport and digital literacy—rose to 28.4% of the Gender Budget 2020–21, but have since declined to 1.5% in FY22 and 1.7% in FY23.

In FY21, this COVID-19 responsive expenditure principally focused on social protection with direct benefit transfers of Rs 500 for 200 million PM Jan Dhan Yojana women account-holders and LPG connections through Ujjwala Yojana. However, with these schemes having been discontinued, the allocation for social protection fell to about 1% of the GBS in FY22.

The spending on schemes for digital literacy, public transport, prevention of domestic violence and skill training also remains low. A small allocation of Rs 120 crore was made for rural digital literacy under the PM Gramin Digital Saksharta Abhiyan in FY22, which declined by 17% to Rs 100 crore in FY23. The expenditure on public transport was driven by the sole scheme for Safety of Women on Public Road Transport, whose allocation fell by 86%, from Rs 139.3 crore in FY21 to Rs 20 crore in FY23. However, allocations for the Sambal scheme (for violence prevention) more than doubled, from Rs 258 crore in FY22 to Rs 562 crore in FY23.

Way forward

Between 2005–06 and today, India has made significant gains on gender budgeting, and accounting of gender-related expenditure has improved. The number of ministries reporting gender budgeting has increased from 14 to 40. But this momentum has to be strengthened across ministries, departments, and schemes.

There is a need to enhance efforts for gender empowering programming across schemes. A gender-needs assessment can be undertaken to identify new policies and schemes to deal with emerging priority areas post COVID-19. For instance, this could include mainstream digital literacy initiatives for girls and support-targeted wages subsidies for employment creation in sectors that employ a large number of women and are still reeling under the impact of the pandemic. This includes enterprises related to textiles, handlooms, handicrafts, food processing, retail, hospitality and so on.

The collection of gender-disaggregated data should be a standard practice, especially for centrally sponsored schemes.

Regular gender audits of centrally sponsored schemes and flagship programmes such as the Atmanirbhar Bharat Abhiyan can emphasise the importance of reporting and ensuring gender-balanced distribution of scheme benefits. The collection of gender-disaggregated data should be a standard practice, especially for centrally sponsored schemes. Further, provisions should be made for the Gender Budget to report progress along outcome and output indicators, as done in the Union Budget.

Regular training is crucial to enhance the capacities of gender based cells. Technical support and additional capacity building measures should be provided to Central ministries and states that are yet to adopt gender budgeting. The MWCD can play a leading role in understanding and bridging knowledge gaps by organising inter-ministerial dialogues to understand the barriers keeping ministries from reporting Gender Budgets.

Finally, NITI Aayog and MWCD can partner to develop a monitoring initiative and web portal so that ministries can openly observe the quality, results, and impacts of their Gender Budgets.

(With research assistance from Geetika Malhotra, Seher Jain and Shrushti Singh)