In August 2020, India announced the National Education Policy (NEP), which set the goal to make awareness about vocational skill training accessible to nearly 50 percent of learners across the country, by 2025. The policy acknowledged the issues around information asymmetry and dignity of labour which have made vocational skilling non-aspirational in the past. It then called for the integration of vocational education into the school system, through coordination with skill development organisations and employers.

For those of us in the vocational skilling sector, this was definitely a welcome step. For children, exposure to vocational education will enable better expectation setting and career planning directed towards jobs which are readily available. For youth, this could open the doors for access to new age skills which will be valued by industry in the future. For older workers, it could give them the opportunity to upskill and re-skill themselves to keep up with the shift in demand that has been accelerated this year, due to the pandemic.

However, in the Union Budget 2021-22, there was hardly any mention of skill development. Funds have reduced for education and no additional funds have been allocated for the NEP. The onus of creating aspirations for vocational skilling at a time when youth employed in such sectors are becoming increasingly vulnerable, has thus fallen to the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) fund.

Employment trends during the pandemic

Over the course of this year, youth in India have had to come to terms with their economic vulnerability, which may have been hitherto unexposed. Wages have reduced, vacancies come with health risks, benefits have disappeared. This raises a pertinent question: How is the pandemic going to shape the future aspirations of young people in India?

At Pratham, we turned to our alumni to see if they can help us figure out the answer. A group of 1,473 candidates, who completed their training with Pratham between 2017-2019, participated in three telephonic interviews, each conducted with a gap of three to four months, over the course of 2020. All of these candidates had completed some form of vocational skilling, and 54 percent were engaged in some form of employment as of January 2020.1 It is important to note here that these youth were working in jobs where working at home was not an option, and wages are usually paid based on productivity at work. We asked them their current activity status and aspirations for the future, and here’s what we found:

- April: This was our first contact with the sample participants, right after the national lockdown started, and roughly 16 percent reported that they were newly unemployed. Another 22 percent reported that though employed, they had been asked to return home and were currently not on active duty.

- August: After the announcement of NEP 2020, when sample participants were interviewed, the data was rather alarming. The expectation was that youth who were home would have returned to their jobs, but instead 69 percent now reported being unemployed (a jump of 21 percent). Unsurprisingly, majority of these newly unemployed candidates were those who had returned to their home towns/villages during the lockdowns.

- December: When interviewed for a third time, about 20 percent of youth reported having returned to some form of work, despite the health risks associated with mobility. When probed, most confessed that they simply couldn’t afford to stay unemployed and had to make compromises.

Notably, less than 18 percent of interviewed youth indicated willingness to move beyond the boundaries of their home district. These newly unemployed youth, who had previously migrated across the country for work, were now hesitant to accept new job offers and were fearful about returning to the cities which used to employ them a year ago. While this fear may be temporary and most youth will be driven back to work out of a lack of choice, the labour demand side should be aware that these youth are cognisant of the volatility and vulnerability associated with their employment.

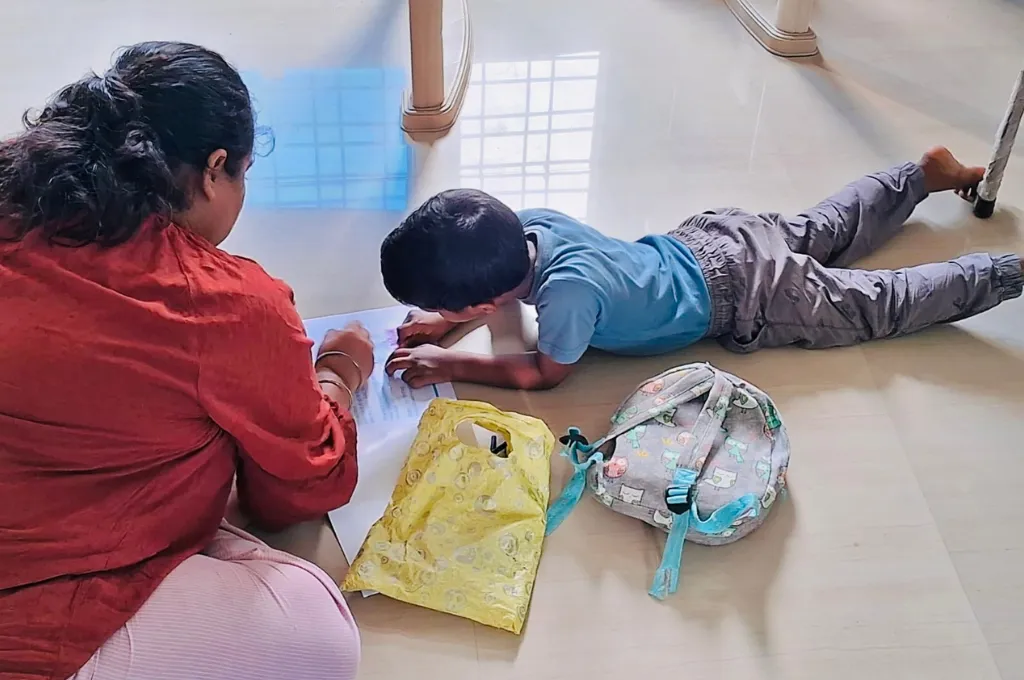

The role of vocational training

Given the challenges faced by blue-collar workers during this pandemic, does further investment in vocational skilling hold merit?

The pandemic has exacerbated the need for valuing skilled individuals in both rural and urban India.

India is a democracy with the youngest and largest workforce (over 500 million with an average age of 29), of which 81 percent of youth are employed by the informal economy, and only an approximate of 15 percent can claim to earn a salaried income. In this scenario, the world of artificial intelligence, robotics, and automation is restricted to a niche corner, while the larger majority is employed by agriculture, construction, and service sector work. If anything, the pandemic has exacerbated the need for valuing skilled individuals in both rural and urban India.

Blue-collar trades are the primary employers in this country today. The NEP offers us an opportunity to tie those jobs to the aspirations of youth. The momentum offered by the introduction of the NEP, should be seized by nonprofit organisations, industry leaders, and CSR partners. Even with limited resources, there are numerous ways to make vocational skilling aspirational. These include:

- Creative curricula: Content related to hands-on skills and vocational trades, must be shared during the academic year as a part of the regular school curricula. Short modules on using tools and learning simple skills can be delivered to normalise the idea of skill-based work. Students can then be asked to complete small projects (community surveys/ home experiments) using resources which are locally accessible. Through a hybrid approach of integrating digital content and practical skills, one can expect a higher appreciation for vocational trades.

- Accessible aspirations: The best evidence for availability of local job opportunities, are the local electricians, masons, beauticians and mechanics. They need to be celebrated as local leaders who can offer realistic career counselling. Not only can they conduct demos of relevant tasks to help increase awareness, they can even offer apprenticeships or training opportunities which will allow children to tailor their aspirations through hands-on experiences.

- Showcasing the skilled: Youth who may have completed some form of skill training in the past and worked in their respective trades need to be invited to interact with children in schools. They can share real experiences of what it feels like to live in a new place, the challenges faced at work, the joy of earning a living and more. This could help build aspirations for young people, demystify concerns, and help students identify new role models.

- Enabling entrepreneurship: The shift in aspirations towards local jobs cannot be implemented without the availability of local businesses. Most of these entrepreneurs have been severely affected during the pandemic, especially those in the service sector. Youth who have returned to their home towns during the pandemic, also demonstrate interest in starting something of their own. Supporting them with access to finance, mentorship and upskilling, could allow rural businesses to grow slowly but surely.

Digital resources and hybrid models have allowed us to reimagine education, skilling, and employment. The NEP offers a window of opportunity for stakeholders to work together to change some historic practices, re-dignify labour, and take the next leap to bring youth in India closer to the future of work.

—

Footnotes:

- This data is based on an internal survey conducted by Pratham. To know more about it please write to annette.francis@pratham.org.

—