Rural India has been in distress long before COVID-19, but over the last few months, the pandemic and the ensuing lockdown have revealed the vulnerability of rural areas to crises. From broken agricultural supply chains to reverse migration—the impact on rural communities has been devastating and has underscored the importance of securing the lives and livelihoods of people across rural India.

One approach to mitigating the effects of crises is building resilience i.e., the capacity of communities to withstand shocks and disturbances, and maintain their usual activities. A core element of this is protecting and promoting livelihoods, particularly agriculture-based livelihoods, given that they are the backbone of India’s rural economy. Focusing on place-based rural livelihoods also has a number of positive knock-on effects such as reducing distress migration, improving food security, and creating educational stability for children.

But how do we build the capacity of rural communities to cope with future crises and shocks? Here are four interrelated pathways that have helped shape the resilience of communities and enabled them to weather crises such as the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

Related article: The future of rural India post-COVID-19

A key component of building resilience is empowering communities to take decisions on issues that affect their own lives. One way of doing this is by creating and strengthening local institutions, such as self-help groups (SHGs), farmer producer companies (FPCs), water user groups, among others. These institutions play an important role in bringing communities together to plan, implement, and manage various development initiatives and in promoting economic development at the local level. When they are adequately invested in, these institutions continue to function and address the needs of the community long after a nonprofit’s intervention ends.

Integral to the idea of building local institutions is a collective approach, rather than one that focuses on working with individual farmers or households. Among other advantages, it offers communities the benefits arising from economies of scale, such as lower investment costs, lower risks, and equitable access to resources. For example, as part of a community-based irrigation project facilitated by Harsha Trust in Odisha, a group of 15-20 farmers were brought together to cultivate cash crops on a 25 acre plot of land. Each farmer had to make an investment of INR 20,000-25,000—significantly lower than the INR 1 lakh each of them would have had to invest for individual borewells. Not only did this reduce costs, it was also a more environmentally sustainable way to manage natural resources.

Across the country, there are numerous examples of how grassroots institutions have helped rural communities weather the current crisis.

Though the advantages of working with communities instead of individuals are obvious in theory, in practice, it requires a significant investment of time and effort to bring people together to work towards a common goal. Building sustainable institutions is also easier said than done and developing the leadership capacity of group members and community resource persons to take decisions is an important step towards this. In the case of Harsha Trust, they chose to do this by building the capacity of a cadre of community resource persons, gradually making them accountable to the community, rather than the nonprofit.

Across the country, there are numerous examples of how grassroots institutions have helped rural communities weather the current crisis. SHGs, FPCs, and other groups have come together to provide relief, financial support, and marketing assistance to their members. An interesting case of how building ownership of institutions can also build resilience is that of an SHG federation, supported by Samaj Pragati Sahayog (SPS) in Madhya Pradesh. In the middle of the lockdown and a liquidity crisis, the SHGs saw a total cash inflow of INR 6.4 crore between April and June 2020. Though this is approximately one-third the amount received by the same SHGs between April and June 2019, it is testament to the fact that its members value the role these institutions play in their lives.

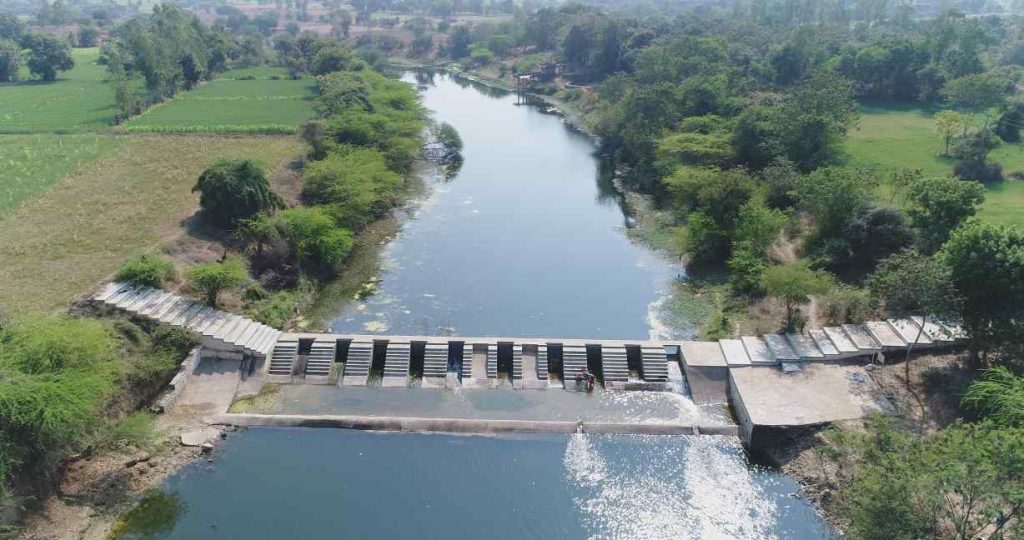

Resilience cannot be built in the short-term, and requires a long-term investment in the aspirations, agency, and assets of rural communities. | Picture courtesy: NM Sadguru Foundation

Women play a critical (yet often, invisible) role in the rural economy, and any successful attempt to build sustainable livelihoods cannot leave them behind. SHGs are a good pathway to engaging women, as they create a safe space for women to interact with each other, while at the same time building their leadership and decision-making skills.

When combined with the process of institution building, women led-institutions have proven that they can support their communities in times of need. For instance, SHGs encourage their members to save, and use lending and borrowing activities to build a surplus from the money collected. In addition to building a contingency fund for emergencies, the surplus can also be used to tide their members over in times of crisis. This was seen during the lockdown, when the aforementioned SHG federation in Madhya Pradesh took the initiative to disburse INR 98 lakh from its own surplus in the form of cash relief.

Women’s role in building resilience should not be limited to SHGs and must extend to participating in and leading other grassroots institutions.

However, women’s role in building resilience should not be limited to SHGs and must extend to participating in and leading other grassroots institutions—such as FPCs or panchayats—that are often assumed to be ‘male’. For instance, 4,800 women SHG members from the federation in Madhya Pradesh own and operate an FPC. They are all small and marginal Adivasi farmers. Their producer company played a major role in supporting its members during the COVID-19 crisis by helping them market their rabi produce, and by providing access to seeds and other essential inputs for the kharif sowing season. It also built an entire supply chain by procuring wheat from farmers, getting it ground into atta (wheat flour), packaging it, and including these 5 kg packets in relief kits that were distributed to 13,000 families.

All this took place during the lockdown, when there were strict restrictions on movement and transportation. The resulting hurdles were managed and overcome by the women of the producer company themselves. The ability to adapt, take initiative, and drive these efforts was not built overnight. It has taken years of women’s active participation in running the FPC—and doing everything from checking quality of the produce to making decisions around what to buy, how much to store, and when to sell—to bring them to this point.

While ensuring women’s participation in local institutions can be challenging initially, it has the potential to uproot deep-rooted patriarchal norms and empower women in the long run.

Women play a critical (yet often, invisible) role in the rural economy, and any successful attempt to build sustainable livelihoods cannot leave them behind. | Picture courtesy: Harsha Trust

Related article: Does NREGA work for women?

The example above attests to the fact that resilience cannot be built in the short-term, and requires long-term investment in the aspirations, agency, and assets of rural communities. In order to be successful, it is critical to work in partnership with the community—gain their trust, listen and respond to their concerns, and identify locally-relevant pathways to secure their livelihoods.

The experience of NM Sadguru Foundation in Gujarat speaks to this. Working with small and marginal Adivasi farmers, they learnt that low land productivity, fragmented land holdings, and the absence of a diversified crop basket were leading to low yields, low incomes, and eventually distress migration to urban areas.

Identifying this as their critical point of intervention, they started working with a small group of farmers, introducing natural resource management and scientific agricultural practices. Over a 15-year period, they tested and refined their approach, while also introducing allied activities such as livestock and poultry rearing. They now work with more than 30,000 farmers. Through a combination of these efforts, the farmers have seen their incomes double, if not triple, along with an increase in land productivity. For instance, the average per acre yield of maize has increased from 5-6 quintals to 14-18 quintals, providing farming households with a greater degree of food security and more diversified sources of income.

An incremental approach creates space to experiment and learn from missteps, which minimises risk and any negative impact on the communities involved.

Once they had successfully increased yields and productivity, they started identifying allied activities that could support the agriculture ecosystem. Sourcing agricultural inputs, such as seeds from distant markets is often expensive and so the organisation started finding ways to build seed self-sufficiency within the community itself. They worked with local youth and promoted them as seed entrepreneurs, and through community institutions, have raised seedling nurseries. Not only has this brought down the cost of seeds and created livelihoods in the local economy, it also meant that in the midst of the transportation shutdown during the COVID-19 crisis, farmers didn’t have to rely on purchasing seeds from outside, and were able to move ahead with sowing the kharif crop.

An incremental approach creates space to experiment and learn from missteps, which minimises risk and any negative impact on the communities involved. If an intervention is scaled early on, without being tested adequately, it runs a higher risk of failing, and this can be disastrous for the community. Additionally, any efforts to improve the ability of communities to withstand economic, social, and ecological shocks need to be highly contextual and adapted to local circumstances; taking an incremental approach factors this in.

A long-term approach needs to be backed by long-term funding, and donors need to be cognisant of this when they commit to funding rural development.

Related article: Photo essay: Fears and aspirations in times of COVID-19

Given the complexity of the process, it is impossible for any single nonprofit or community to build resilience alone. Different stakeholders need to participate in this process. For instance, one of the basic conditions for resilience is investment in public infrastructure such as roads, hospitals, and electricity—all of which can only come from the government. The government also plays an important role in providing social security and social welfare, which can be drawn upon to bolster resilience.

It is also important for nonprofits to engage government agencies and the private sector to build a supportive ecosystem, whether for funding and in the case of agriculture-based livelihoods, for technical, credit, and marketing support.

By now, it is common knowledge that the pandemic and the ensuing lockdown have resulted in the loss of jobs, large-scale reverse migration, and broken agricultural supply chains—all of which together have debilitated rural lives and livelihoods. In order to ensure that the same vulnerable groups are not affected by the next crisis—be it social, economic, or ecological—it is important, now more than ever, to strengthen the capacity of rural communities to withstand shocks.

It is important, now more than ever, to strengthen the capacity of rural communities to withstand shocks.

Though not without their challenges and complications, the experiences of nonprofits that work in a variety of rural settings demonstrate that a gradual, long-term approach to partnering with communities to develop sustainable rural livelihoods has the potential to build a degree of resilience and support communities in responding to crises and shocks. With rural India living through an uncertain present and facing an undetermined future, the role of building and enhancing resilience can no longer be sidelined.

Disclaimer: Axis Bank Foundation supports IDR for research and dissemination on the issue of rural livelihoods.

—

Know more

- Learn more about the concept of rural resilience.

- Understand how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the livelihoods of smallholder farmers engaged in floriculture in Tamil Nadu.

- Read stories that highlight the multiple ways in which the COVID-19 crisis has impacted rural India.