Most organisations, when confronted with problems such as loss of market share, sources of revenue drying up, or recurring losses, begin to look for solutions. Organisations are comfortable dealing with ‘tangibles’ such as costs, production figures, and profits. Some of them undertake a SWOT analysis to figure out what they can do, both externally and internally, to stem the rot. Looking outward, they may rework their strategies, and tap new markets and sources of revenue. Looking inward, they often begin to wonder whether a re-structuring is needed to bring greater efficiency in the system.

Outputs and processes

Many organisations overlook the fact that outputs are dependent on processes and the internal climate of an organisation, both of which are ‘not-so-tangible’. These include a sense of responsibility or ownership, the staff’s level of confidence, the quality of supervision, the prevailing forms of decision-making, and the motivation levels within an organisation.

[quote]Many organisations overlook the fact that outputs are dependent on the internal climate of an organisation.[/quote]Often, organisations hire consultants to help them re-organise themselves. For the client as well as the consultant, dealing with tangibles is more attractive than dealing with the not-so-tangibles. They gather at the drawing board, and a new structure begins to emerge in quick time—about two to three months. Accompanying the newly envisaged structure, more often than not, is a new pay structure that is put in place to match the reorganisation. These are implemented with the full backing and support of the top management.

By doing this, the immediate problems (where the shoe pinches the most) appear to be addressed. There may be a sense of relief among the top management—they have ‘done’ something substantial to confront the declining fortunes of the organisation.

The static and the dynamic

Structures are static—relatively permanent. You do not change the structure of a building or an organisation every now and then. If you were to do so, it would create far too much instability and uncertainty. Having said that, the life-blood of an organisation—that which lies in the not-so-tangible underbelly—is its processes, which are dynamic in nature.

[quote]Processes, which are not-so-tangible, are the life-blood of an organisation.[/quote]These are under constant flux, shifting from time to time. These include processes of communication, leadership and influence, decision-making and problem-solving, to name a critical few. The real action lies in the processes—all the turf wars, the competitiveness, the power struggles, as well as a desire to make an impact and be recognised for it. The processes determine whether a well-thought-out strategy will bear fruit or not.

Related article: The leadership crisis

The inherent danger of prioritising structures

The danger of focusing predominantly on structures and paying next to no attention to processes is predictably wrought with problems. These include organisations experiencing a sense of ‘frozenness’—they neither seem to be able to move forward nor revert to an earlier state of equilibrium.

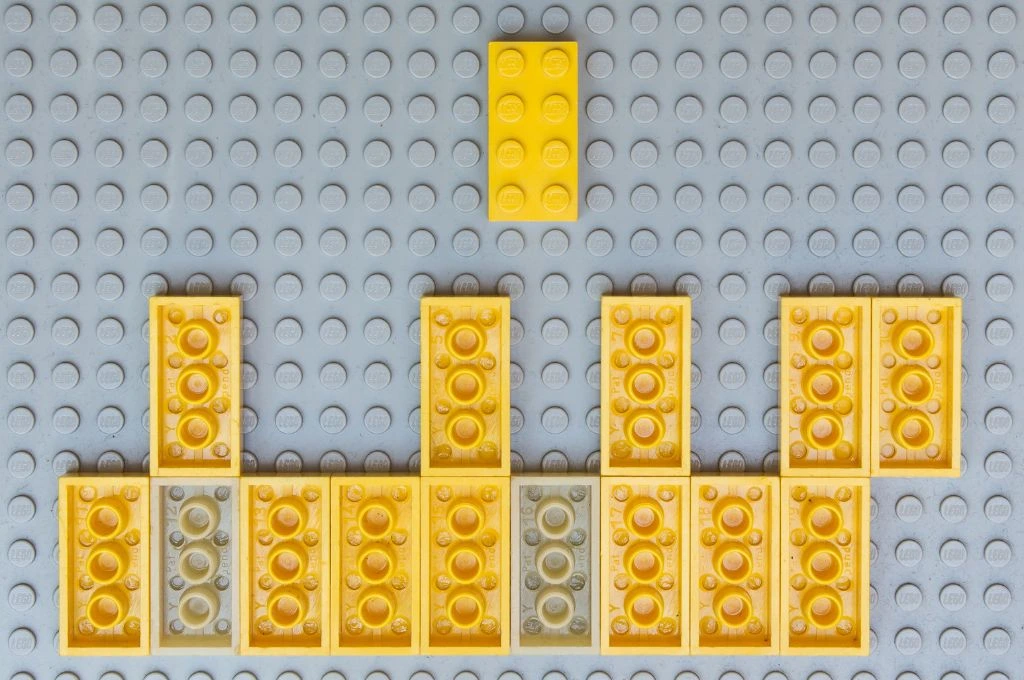

Focusing only on re-structuring without paying attention to processes is wrought with problems | Photo courtesy: Pixabay

Structure determines the process, and the process determines the structure. If you seat people in a row (structure), it will determine the process and flow of communication. If you want a substantial amount of face-to-face interactive communication (process), seating people in a circle (structure) is likely to facilitate that. The decision to focus on structures, the relatively static aspects of an organisation, or to address the issues embedded in the not-so-tangible processes, is a difficult one to make. Short-term and quick versus long-term and sustained come into play.

Tracking performance—the underlying assumptions

Initiating or redoing a performance assessment system seems to be a favourite among organisations facing dire circumstances. They espouse the belief that if they ‘fix’ the performance, the rest—in terms of motivation and creativity—will follow. Tracking and monitoring performance provide data and feedback that will highlight the shortfalls and, thereby, egg on the employees, particularly senior staff, who are supposed to shoulder the responsibility of delivery, and put in fresh energy to enhance their output.

However, playing the ‘catch-up’ game creates a reactive and defensive climate. The motivation to move towards achievement is different from the motivation to move away from failure. The first may be called an ‘approach’ stance and the latter an ‘avoidance’ stance. Stimulating the senior staff to pull their weight and take responsibility to enhance organisational performance is more likely to be achieved through an ‘approach’ stance, wherein the senior staff seeks growth and accomplishment rather than avoids failure. Understanding and responding to the motivational needs of senior staff facilitates this movement. Processes, including motivation, lead to performance. And not the other way around.

Chief executives who recognise that the process of change is long-term and are willing to commit to a period of three to five years, have the orientation to really build an organisation. Concretely, this translates to the following: while a chief executive must address the immediate needs of the organisation (which may include dealing with some of its more static aspects such as structures and standard operating procedures), they simultaneously have to invest energy into opening up blocked communication, channelling influence, and enhancing the effectiveness of decision-making and problem-solving.

Related article: Waking up to the talent you already have

Where to focus?

Organisations facing problems may need to have a bifocal view—one, focus on reducing and rectifying flab in its structures and systems. This may include the organisation structure including re-allocation of staff and responsibilities, deploying resources to strengthen some departments or functions, revisiting the performance management system, the incentive system and the salary structure.

[quote]Organisations facing problems may need to have a bifocal view—changing structures and revitalising processes.[/quote]The other, opening up channels of communication and information-sharing; broad-basing the influence processes ensuring that the best ideas can surface, and are used to address problems; taking decision-making to the people in direct contact with the problems; and creating forums where staff can interact, share and discuss problems they face and their solutions.

In organisations facing problems, there is often a lack of a sense of ownership among staff, including people disowning responsibility for problems and not investing energy to address them. Often, accurate communication about the actual state of the organisation and the functioning of the departments is a casualty.

Providing honest and relevant information about different aspects of the organisation to a particular level and department is the start of building a shared understanding of the issues at hand; it opens up the possibility of collaborative problem-solving. In addition, the direct involvement of those staff affected by a problem while working to resolve the issue is likely to lead to better acceptance and more effective implementation of solutions.

Structure and process—striking a balance

The combined effect of changing structures and revitalising processes is likely to boost market share and revenue on the one hand, and create a vibrant organisation that is perpetually renewing itself, on the other.

I believe that all development is an act of faith to begin with. There is no guarantee that a child will grow and develop into the kind of person that the parents want them to become. Investment in the development of an organisation is no different. The chief executive needs to believe that this nature of investment is worthwhile and will prove itself in the medium run. Striking a balance between the investment of energy in more static structures and in the relatively more dynamic processes is where organisations need to take a call.