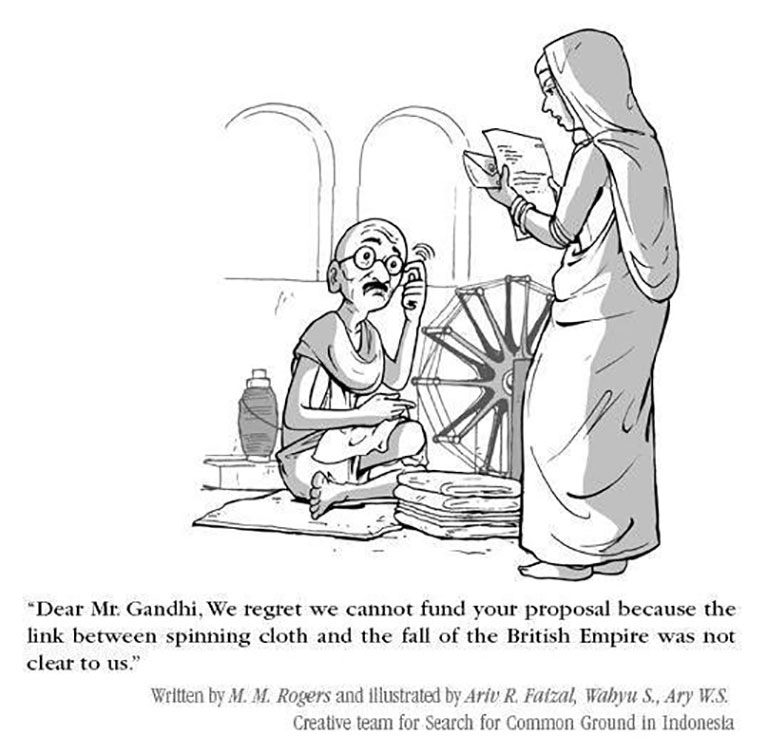

An incisive editorial cartoon shows Mahatma Gandhi being read a letter stating that his funding proposal for spinning cloth is being rejected because the link between the proposal and the struggle against the British empire is not clear. The response is arrogant, foolish and shows a complete inability to make sense of socio-economic and political processes unfolding at the time. The use of the spinning wheel is particularly pointed: Gandhi made symbolic use of it not only as a tool of political action for shaking the economic basis of British imperialism, but for building a culture of self-reliance among Indians.

As a civil society practitioner, this cartoon has stayed with me as I encounter very similar behaviour from too many of today’s philanthropists.

The retreat of the welfare state, rise of neo liberalism and growing concentration of wealth has created the conditions for an explosive growth of philanthropy and its heft on the world stage. As enough studies have shown, there has never been a better time for philanthropy in terms of its expanding volume and reach. Even an ambitious global compact like the Sustainable Development Goals looks to philanthropy for resources in an era of dwindling state resources. In view of its growing size and clout, fundamental moral questions about the role of philanthropy in socio-political change needs further and more careful investigation.

There are worrying signs about how philanthropy’s growing influence is shaping narratives about global social change.

Many would argue that the philanthropic capital being generated is part and parcel of a ruthless economic order which concentrates profit and wealth in the hands of few. Therefore, turning to the super-rich for salvation to society’s problems poses real ethical dilemmas. But alongside that question, there are also worrying signs about how philanthropy’s growing influence is shaping narratives about global social change.

Philanthropy primarily operates through civil society and civil society, by design, plays a critical role in the architecture of modern democracies. In these times of dramatic change in democracy, development and politics, the impact of philanthropy on shaping civil society deserves more scrutiny.

Two spheres of civil society

My fear is that two distinct civil society spheres are emerging, working in parallel and at times at cross-purposes. One sphere embodies the values and principles of the older non-profits and other collectives including social movements, mass organisations and community-based groups. The second sphere is located in the market and technology spaces and is being rapidly populated by new-age non-profits, social enterprises and online collectives.

There is a fundamental contradiction between the two spheres. The old non-profits’ worldview is premised on an integrated social sciences and systemic approach, in which the complexity, interdependence and interrelatedness of diverse factors at work in a system need to be understood and addressed in order to change that system. In the approach of the new-age non-profits, by contrast, the emphasis is on finding technology based-managerial solutions for complex social, economic and political issues.

Bubbles

Donors who look at the world through a techno-managerial lens encourage and enable civil society groups to zoom straight into the middle of the problem at hand, without the need to engage with the contextual difficulties of the issue. In this process the real world, existing in all its complexity is circumscribed or left behind. It is like creating a bubble in which technical linear solutions appear to be solving complex problems.

The entire conversation around the fundamental issues being addressed gets artificially limited to the confines of the bubble. These bubbles are then presented as fertile ground for systems change, innovation and success stories. These successes and innovations lead in turn to more investment, which results in the bubble becoming bigger and more celebrated.

The complexity of the socio-economic and political systems and human behaviour remain peripheral to the story—until they puncture the bubble. In the meantime, donors and civil society organisations have moved on to creating new bubbles.

The techno-managerial approach therefore artificially converts endemically wicked problems of development and human society into ‘solvable’ problems, deliberately separating the problem from its context, system and location so that the intervention does not need to engage with the larger problems of the system or society.

For example, an NGO working on safe drinking water might go to an Indian village and install a hand-pump for the villagers oblivious to the fact that in a society deeply divided by caste, water is one of the critical markers of purity and pollution, which has caused serious conflicts including even riots and murders over who gets access and who is denied it. Even though the hand-pump might have led to even greater caste tensions in the village, the NGO would count it a success if it is installed and provides potable water. This approach can provide in the short run the ‘high’ of success and tick marks on the log frame but it does not provide the analytical grid and social action tools and tactics to address the larger systemic questions and influences. In the longer run, such ‘band aid’ solutions fail because they focus on the manifestations and not the root and structural causes of poverty and injustice.

The triumph of the technocrats

The rapid expansion of philanthropy has strongly supported the new age non-profits, which has also meant declining resources for the more traditional non-profits. The inclination of donors towards the newer kinds of civil society can be attributed to precisely that increasing emphasis on results and impact; arrogance in believing that complex parts of endemic problems are ‘solvable’ through short project cycles; inability to engage with or comprehend the interconnectedness of a socio-economic and political system; faith in top-down blueprints for success; the preference for business management practices and solutions located in technology or the market sphere; and, at an operational level, increasing numbers of philanthropy managers and donors with MBAs and backgrounds in running businesses, unlike the previous generation of leaders who were primarily a mix of academics from social sciences and practitioners from the ground.

Such heavy investment by philanthropy in newer forms of social enterprises is gradually changing the character of civil society to the serious long-term detriment of society and, more importantly, to the fundamentals of democracy. Apart from its many other tasks, which have included some basic service delivery for the most excluded populations, civil society has traditionally played two important functions in the post-war era, both in the global north and in the post-colonial societies of the global south.

The first function is that of challenging power—particularly from the vantage point of the most powerless and excluded groups. In a democracy, civil society plays a crucial role in seeking the accountability of power (primarily state power, but also other sources of power)—its so-called ‘watchdog’ function.

Very often, ideas for change do not come from the centre, but from the margins, prompted or articulated by civil society.

The second function is of creating and nurturing new ideas, experiments and alternatives for transformative change. Very often, ideas for change do not come from the centre, but from the margins, prompted or articulated by civil society.

For instance, in the 1950s and 60s, India took the path of building large dams for the country’s irrigation and water needs. Despite the fact that the mammoth financial and environmental costs along with human costs of displacement and loss of bio-diversity, were soon recognised, the state continued to favour big dams. Only when civil society groups started building local models of micro-watersheds and irrigation systems in sync with local ecosystems and at almost no cost did the development discourse begin paying attention to these alternatives.

The decline in civil society’s ability to perform these two critical functions does not bode well for the future.

How philanthropy risks missing its way

The unfolding global narrative of populism, fundamentalism and the rightward shift of politics as reflected by Brexit or leaders like Trump, Erdogan, Orban, Netanyahu, Modi and Duterte, presents an exceptionally challenging time for the world.

In a milieu where power is becoming concentrated in fewer hands across the world, the need for a strong discourse on making power accountable is fundamental to the future of democracy. In this context, philanthropy needs to pause and rethink its own relevance and role. It also needs to ask the fundamental question about the aim of the human project. History has taught us that the provision of health, food and shelter has never by itself ended misery, slavery, exploitation, and indignity.

The human project—and with it the philanthropic endeavor—should be about human dignity and justice. Philanthropy cannot remain a bystander while the hopes and gains of human history achieved in the twentieth century are reversed. It cannot look the other way and pretend to play an important role by fighting the manifestations of poverty and not engage with structural questions of poverty, injustice, indignity and enslavement. We certainly need, bold new and edgy philanthropy, which can stand on the right side of civil society—defending democratic spaces and promoting human rights.

This article was originally published in Alliance Magazine. You can read it here.