Media plays an important role in informing and shaping public opinion around major issues. Amartya Sen has argued, “It is not likely that India can have a famine even in years of great food problems. The government cannot afford to fail to take prompt action when large-scale starvation threatens. Newspapers play an important part in this, in making the facts known and forcing the challenge to be faced.” It has been found that Indian states with a higher newspaper circulation rate perform better in terms of providing calamity relief and distributing food under the public distribution system. Media can impact large-scale outcomes through its reportage. This, then, begs the question: How does the media decide which issues to raise?

The answer commonly veers from the media picking sensational topics to the ideological inclinations of media houses and covert or overt pressure from stakeholders such as the government, businesses, and communities. The demand aspect—what readers prefer and want to read—is largely missing in this narrative. Being a competitive and profit-making industry, demand dynamics play a pivotal role in deciding what gets covered by the media and which issues get more space. There is a significant and persistent trust deficit between the people and the media in India—only 38 percent of Indians trust most news, compared to 65 percent in Finland, 54 percent in Brazil, 50 percent in Thailand, and 43 percent in Australia. Low trust is usually ascribed to media bias, and this perception is natural in a country where close to 70 percent of media revenue comes from advertisements and 30 percent from reader subscriptions.

At the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy think tank, we explored this demand-side relationship and attempted to understand what influences media reporting. Focusing on English-language media, using land conflicts involving communities as the focal point, and comparing the occurrence of conflicts vis-à-vis coverage, we found that reader interest plays a key role in determining media reporting. Reader interest, in turn, is driven by the location of the conflict and of the reader, the intensity of the conflict, and the involvement of a known entity (person, corporation, etc.). This does not mean that reporting may not be ‘influenced’ or ‘sensationalised’, but rather that there are other, more objective reasons as well that play a key role in deciding coverage.

Upon analysing 714 ongoing land conflicts involving communities tracked by Land Conflict Watch, we found that disputes occurring in rural areas account for more than two-thirds of the total. This seems intuitive, since larger conflicts involving communities mostly pertain to issues such as land acquisition, which are more likely to occur in rural areas than in areas that are already urbanised. However, the location of the conflicts reported in the media present a different picture. Leveraging the Global Database on Events, Language and Tone, arguably the world’s most comprehensive database monitoring news media, we derived a list of 58 land conflicts that are covered by the media and found that 39 of them were urban issues. Thus, while rural areas account for 70 percent of the actual occurrence of land conflicts, nearly 67 percent of the conflicts reported by the media are from urban centres.

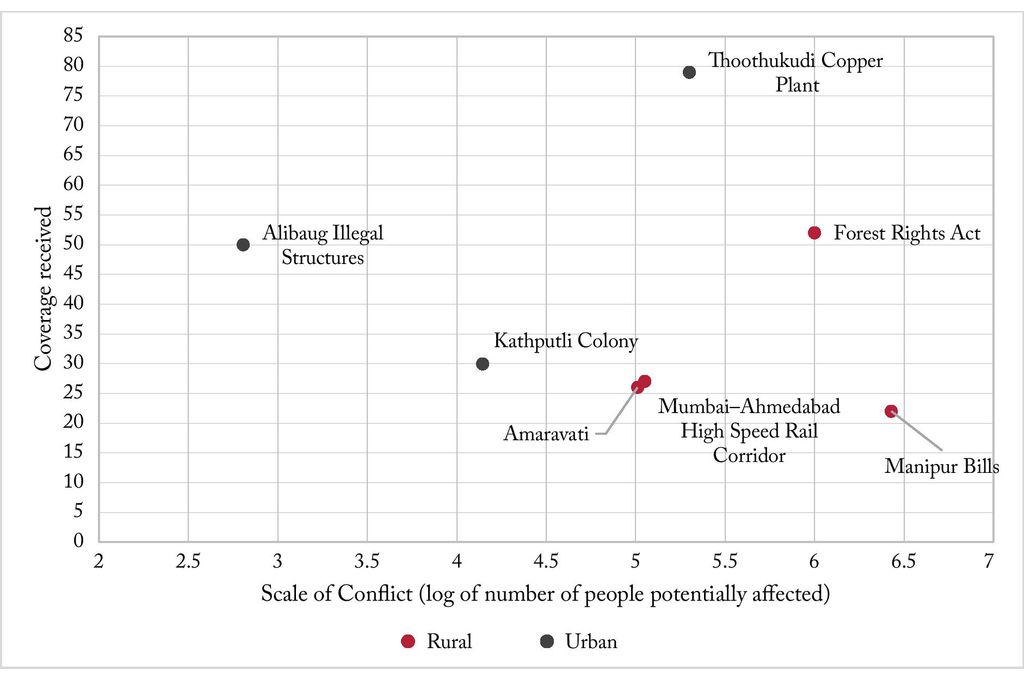

Upon delving deeper into seven illustrative case studies, we found that each urban conflict is also covered more deeply, despite the fact that rural conflicts impact a larger number of people.

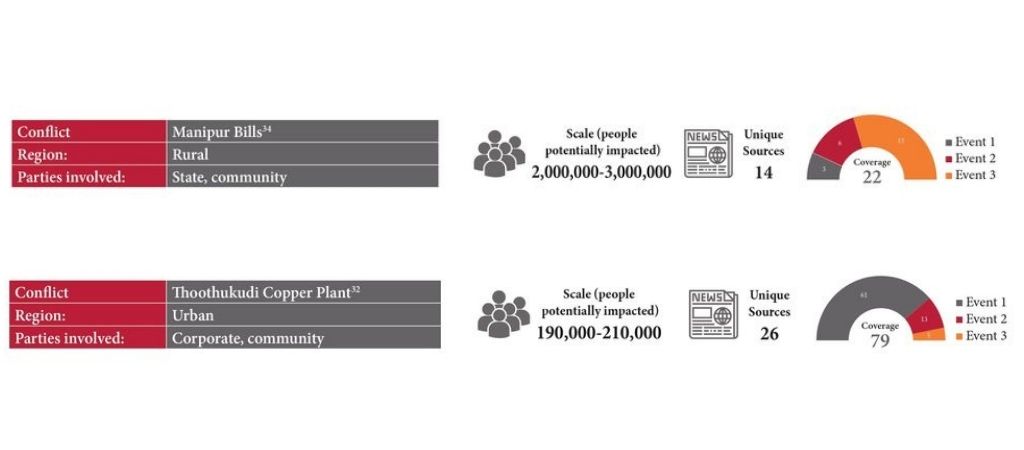

These seven case studies comprised three urban conflicts—Alibaug Illegal Structures, Thoothukudi Copper Plant, and Kathputli Colony; and four rural conflicts—Mumbai–Ahmedabad High-Speed Rail Corridor, Amaravati Capital City, Manipur Bills, and Forest Rights Act.

The four rural conflicts were about 15–20 times as large as the three urban conflicts in terms of the number of people affected, and yet they received around 20 percent less coverage. For example, the Manipur Bills conflict, despite potentially impacting the largest number of people among all seven conflicts, was covered the least. On the other hand, the Alibaug Illegal Structures conflict was the third most widely covered, despite impacting a significantly smaller number of people.

Conflicts involving known entities tend to be covered more, irrespective of their role in the conflict. The Alibaug Illegal Structures conflict, for instance, involves people (presumably) from a certain wealth-based class. The core conflict pertains to the demolition of 160–170 illegal structures that had been built in violation of environmental norms. However, one of the bungalows belonged to Nirav Modi, and therefore a large chunk of coverage was driven by his name in the headlines. The reporting was thus driven by a known name, irrespective of the scale, severity, or, most interestingly, the role of that well-known person in the conflict.

The next critical driver of coverage is the severity of the conflict. Among the conflicts we chose to study, the Thoothukudi Copper Plant issue was covered the most. In addition to being an urban conflict involving a known corporation, a key element driving its coverage was the fact that 13 people unfortunately lost their lives protesting against the plant. This particular event garnered the highest share of the coverage. Likewise, in the Manipur Bills conflict, nearly 60 percent of the coverage was devoted to the incident where several people were killed at the Churachandpur protests. While we may argue that the severity of the conflict is a contributing factor for wider coverage, it does not seem to be uniformly applicable, which brings us back to the potential urban–rural divide. In contrast to the Thoothukudi Copper Plant conflict, the Manipur Bills conflict, which affected the largest number of people and involved the loss of several lives, received the least coverage.

Media reporting is driven by reader interest

This disconnect could be attributed to the fact that the majority of the 40 million English newspaper readers reside in metropolitan centres, whereas the 470 million readers of regional newspapers are largely concentrated in smaller towns and rural areas. Since a majority of the readership of English-language media is centred in and around urban areas, covering issues that occur in close proximity to these readers is more important to them than potentially bigger conflicts that are unfolding in a distant, rural setting.

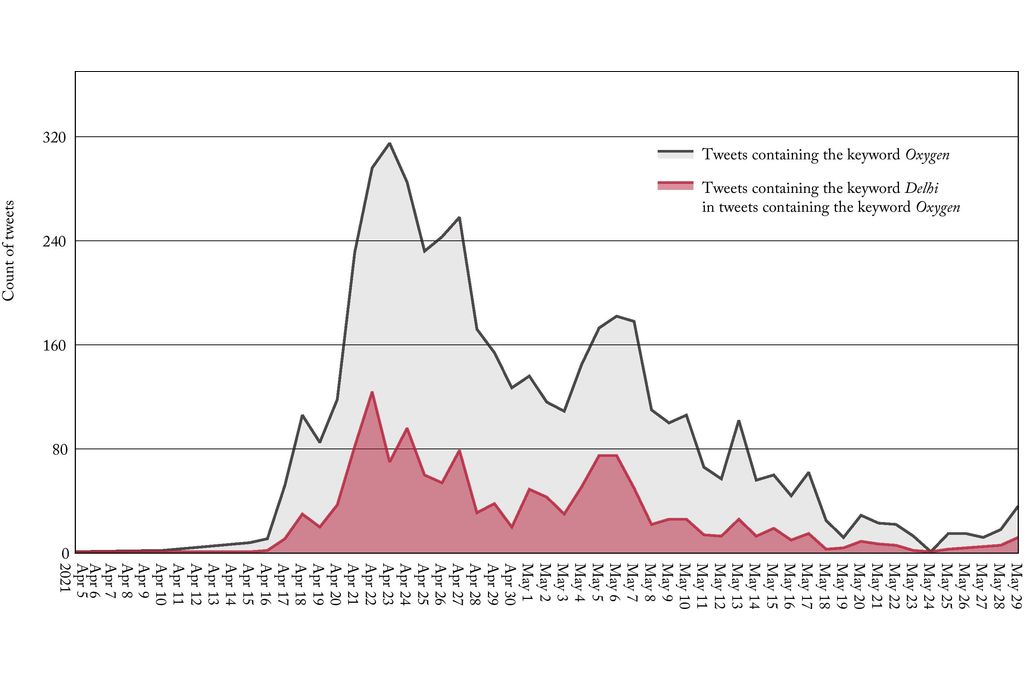

Our framework of reader interest driving coverage was applied to other contexts and issues, which revealed that the framework holds up. We studied the media coverage and response to the COVID-19 oxygen crisis. During the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in India, several fault lines, such as inadequate provisions of medical-grade oxygen, came to light. However, the talk on the oxygen crisis seemed to be centred around a few metropolitan areas, even though the problem itself was presumably nationwide. In order to confirm this and to derive insights, we examined the Twitter handles of nine media houses by scraping their tweets from the beginning of April 2021 to the end of May 2021—arguably the worst-hit period during the second wave. We filtered the tweets to see how many of them were related to the oxygen shortages; another round of filtering gave us tweets specifically about Delhi’s oxygen shortage.

Of all the scraped tweets mentioning ‘oxygen’ during this time, Delhi’s share was about 30 percent. Considering that Delhi accounts for only 1 percent of India’s population, a 30 percent share seems inordinately high. The crisis would have been much worse in other, less urbanised regions, since health infrastructure in smaller towns and rural areas is likely to be poorer than in big cities like Delhi. Despite making up only 1 percent of the country’s population, Delhi accounted for 3.2 percent of total hospital beds, 2 percent of ICU beds, and 2 percent of ventilators available at all hospitals across India.

The spotlight given to Delhi confirmed the urban-centred nature of reporting driven by the preferences of an urban-based readership. By highlighting Delhi’s oxygen shortage, the media exerted its influence and pressure to force a response from policymakers. However, an improvement in Delhi’s oxygen situation may not necessarily have reflected a pan-India improvement of the crisis, which is what the tweet pattern would appear to suggest.

Our study presented two primary conclusions. First, reader interest plays a key role in shaping coverage. Second, what readers want to consume may or may not align with reality and with what needs more urgent redressal from a larger, countrywide perspective. Therefore, the media industry must perform a tough balancing act to stay profitable by giving people what they demand, while simultaneously covering information that people ought to know. A critical question to pose here is, even in an ideal world devoid of inherent media biases or influences, would reporting still be perfectly reflective of reality? Our research suggests that it would not; a wedge between reporting and reality would persist on account of the heterogeneity of readership.

—