In 2014, the government of Madhya Pradesh launched a comprehensive school management programme—the Madhya Pradesh Shaala Gunvatta (MP School Quality Assurance) programme—in an effort to improve the management of public schools. This programme is one among many management-related interventions in the education sector, where management quality has been found to influence test scores and school productivity. However, evidence on whether such interventions are able to change actual behaviours and outcomes at scale remains scant.

To understand this gap, Karthik Muralidharan and Abhijeet Singh examined the impact of the Shaala Gunvatta programme as part of a project funded by the International Growth Centre, J-PAL Post-Primary Education Initiative, Economic and Social Research Council, and Department for International Development’s RISE programme. The intervention was the precursor of a variant that has since been rolled out to more than 6,00,000 schools across India and is expected to eventually cover 1.5 million schools. The programme entailed:

- Developing school rating scorecards by conducting independent and customised assessments of school quality to identify strengths and weaknesses. The scorecards were based on indicators in seven domains—mentoring, management, teacher practice and pedagogy, student support, school management committee and interaction with parents, academic outcomes, and personal and social outcomes.

- Devising school-specific improvement plans with concrete action steps based on the school assessments. These plans aimed to set manageable targets for improvement that schools could achieve step by step.

- Ensuring regular follow-ups by block-level supervisors to monitor the schools’ progress and provide guidance and support. This was an integral aspect of the programme that sought to motivate schools to deliver continuous improvement.

- Ensuring school inspectors, all school staff, and parent representatives were involved in the assessments and the design of improvement plans.

From among 11,235 schools across five districts, 1,774 elementary schools were randomly selected to receive the programme (treatment schools) and 3,661 schools were assigned to the control group. The experiment’s primary outcome of interest was student learning, which researchers calculated using three data sources: student scores attained on independently designed Hindi and maths tests; student scores on official assessments; and aggregate scores of all the schools on the Pratibha Parv annual assessments, which are administered to all students from grades 1–8 in the public schooling system. Additionally, student and teacher absences were tracked and principals, teachers, and students were surveyed.

Interestingly, the authors learnt that the programme was largely ineffective. Nevertheless, it was viewed as a success and was scaled up to approximately 25,000 schools across the state.

Here’s what didn’t work and why

1. Lack of sustained oversight

Although the school assessments were comprehensive and informative, there was no change in the frequency or quality of supervision as a result of the programme. The block-level supervisors did not increase their monitoring of the schools. School management committees did not play a more active role either. Moreover, there was no difference between treatment and control schools in terms of the content of official feedback recorded in the inspection registers that the schools maintained. Thus, all evidence suggested that the school ratings did not inspire any meaningful follow-up.

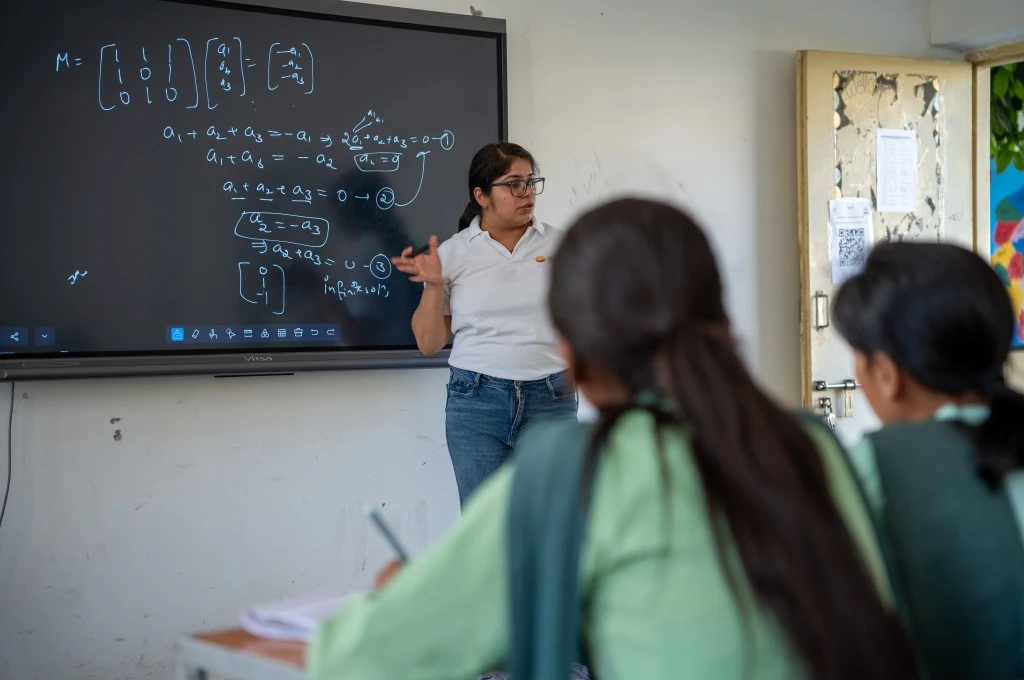

2. No improvement in pedagogy or effort

Although the assessments and school-improvement plans could have led to improved teacher effort and classroom processes, no evidence of this was found in the schools. Teacher absence rates remained high (33 percent across the board) and teacher effort was unchanged. Their instructional time, the use of textbooks and workbooks, and how much they checked student homework remained the same. Student absence rates were also high (44 percent) and were not affected by the programme.

3. Unaffected learning outcomes

The programme failed to demonstrate an impact on student learning outcomes both in the short run (three–four months after the intervention) and over a longer term (15–18 months later). This applied to both school-administered tests and tests that were independently administered by the research team.

Despite the evidence that highlighted the programme’s ineffectiveness, it was scaled up to approximately 25,000 schools across the state. The researchers carried out extensive interviews with principals, teachers, and field-level supervisory staff in six districts during the scale-up to identify the reasons for the programme’s ineffectiveness.

This is what they learnt

1. Implementation was poor

The officials recalled that the momentum generated by the programme largely dissipated after the preparation of work plans. Additionally, although the schools and teachers repeatedly mentioned that pedagogical support and accountability in schools were lacking, neither of these was reported to having changed as a result of the programme. This means that the programme failed to remedy the gaps of the system through improved pedagogy or governance. In fact, it was largely viewed as an exercise in administrative compliance, which officials demonstrated by submitting their paperwork on time. This was a significant departure from the exercise in self-evaluation and improvement that the programme aimed to be.

2. Valuing the appearance of success, rather than actual impact

A striking insight was that although the programme did not facilitate changes in school practices or student learning outcomes, it was perceived as a success by senior officials and continues to be scaled up. The interviews revealed that there was a disconnect between the programme’s objectives and how it was perceived by its implementers. Although the programme prioritised continuous support and self-improvement, those implementing it only focused on completing paperwork and submitting assessment reports and improvement plans. There was also a disconnect between the role the education officials were expected to play and how this role was perceived by others in the system. Although they were meant to monitor, coach, and hold schools accountable, they were perceived as conduits for communication (especially paperwork) from schools to the bureaucracy.

Bureaucratic incentives are geared more towards the appearance of activity as opposed to actual impact.

Frequent changes in education policy and programmatic priorities also resulted in negative field-level consequences, such as a lack of engagement by implementing staff. This led the implementers to believe that government policies are impermanent, often designed without considering implementation constraints, and frequently abandoned or changed. And, the interviews indicated that bureaucratic incentives are geared more towards the appearance of activity as opposed to actual impact. As a result, completing school assessments and uploading school improvement plans at scale were the main elements that were monitored. Based on these metrics, the programme was a success.

How can public service delivery be improved at scale?

In light of their findings, the researchers offered the following recommendations to improve public service delivery at scale.

1. Better incentives

Many existing studies have outlined the positive effects of well-designed interventions to improve the performance of public sector workers, including those in the education sector. The failure of this programme showed the difficulty of improving outcomes without incentivising front-line staff and supervisors to do so. The partial implementation of the programme reflects how bureaucratic incentives were skewed in favour of what was being monitored, while other metrics were ignored.

2. Better outcome visibility

Senior officials only monitored easily visible aspects of programme performance, and the programme even worked till the point where outcomes were visible to senior officials (completed school assessments, uploaded improvement plans). However, the effect ceased at the point where outcomes were no longer easily visible (for instance, in the case of learning outcomes and classroom effort). Thus, investing in ensuring improved measurement and integrity of outcome data would enable better monitoring of the programme and yield better results.

3. Staffing

The programme merely added responsibilities to departments that are already overburdened and understaffed. Given the importance of dedicated programme staff, the programme may have been more effective if its staff capacity was higher. This would have enabled them to conduct follow-up visits to schools and comprehensively monitor their progress against the targets set out in the improvement plans.

Although solely improving these factors may not successfully improve school governance and its related outcomes, they can serve as effective first steps.

—

Know more

- Read the complete research paper that this article is based on.

- Listen to IDR’s podcast that discusses the pros and cons of government schools and private schools.

- Read this article on the cost of teacher absences in India.