Cities are both drivers of progress and key contributors to climate change. Despite occupying just 3 percent of the planet’s land area, these vital centres of modern civilisation generate 70 percent of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions due to their dense population and energy-intensive infrastructure. Halfway through the century, 70 percent of the global population will live in cities, making existing urban areas denser, warmer, and more prone to floods.

India itself is on the quick march to urbanisation, with 40 megacities and 2,500 rapidly growing towns. By 2030, half of India’s population will live in these cities, placing them squarely in the path of climate’s fiercest challenges: heatwaves and floods. One study shows that urbanisation has enhanced warming in Indian cities by 60 percent compared to surrounding non-urban areas. Urban floods, on the other hand, impacted 162.5 percent more people in 2021 than in 2012.

Climate impacts take a heavy toll on urban residents, triggering vector-borne diseases, threatening livelihoods, and undermining the overall quality of life, particularly for the socially and economically disadvantaged.

Yet, there is hope. As India’s urban landscape continues to develop, the country has the unique opportunity to construct cities that not only withstand climate crises but prosper despite them. The solution lies in the climate action plan (CAP), a comprehensive framework designed to transform these emerging urban centres into models of resilience and sustainability.

The ABC of a CAP

A climate action plan (CAP), in the Indian context, is a strategic framework designed to address climate change at the urban level. It aims to measure and reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, enhance resilience to climate impacts, and promote sustainable urban development.

Aga Khan Agency for Habitat – India (AKAH) is an organisation working to build habitats that are resilient to disasters and climate change. It has been working with Mira Bhayandar Municipal Corporation (MBMC), a growing city in western Maharashtra, to design and implement a CAP that will guide the next few decades of its development. The CAP is part of the AKAH’S Urban Habitat Risk Resilience (UHRR) programme, which aims to showcase integrated solutions that address the urban heat island effect through cooling and energy-efficient solutions for the built environment.

Situated north of Mumbai, in the district of Thane, Mira Bhayandar is a 79-sq-km urban area that was a loose agglomeration of 19 villages not long ago. In the last 30 years, rapid urbanisation has resulted in a 393.94 percent increase in its built-up area, owing chiefly to its proximity to Mumbai. This urban expansion has led, among other things, to a temperature difference ranging from 0.95°C to 1.27°C between the city centre and its outskirts. The mean land surface temperature now varies from 30°C to 47°C. Rising heat, coupled with the critical need to mitigate the imminent impacts of climate change, prompted the MBMC to formulate a climate action plan for the city.

The key components of a CAP are:

- Baseline assessments for GHG emissions and climate risk

- Tailored sectoral strategies for mobility and air quality, energy and buildings, waste management, urban flooding and water resource management, and urban greening and biodiversity

- Goals and targets for mitigation and adaptation

- Implementation roadmap through stakeholder engagement

- Monitoring and reporting

This article captures some of the key lessons from designing and implementing such a plan.

We need to get an early start on cities

It’s vital to catch a city young. A young city that integrates climate resilience into its master plan is more likely to achieve its net-zero targets than an older city, because it is harder to retrofit solutions and implement corrective measures at scale when social, civic, and economic systems—and a city’s infrastructure—are set in stone. Developing a CAP for a young city is therefore not just a timely but a necessary intervention. Here are some of the factors that work in its favour:

1. Redevelopment done right

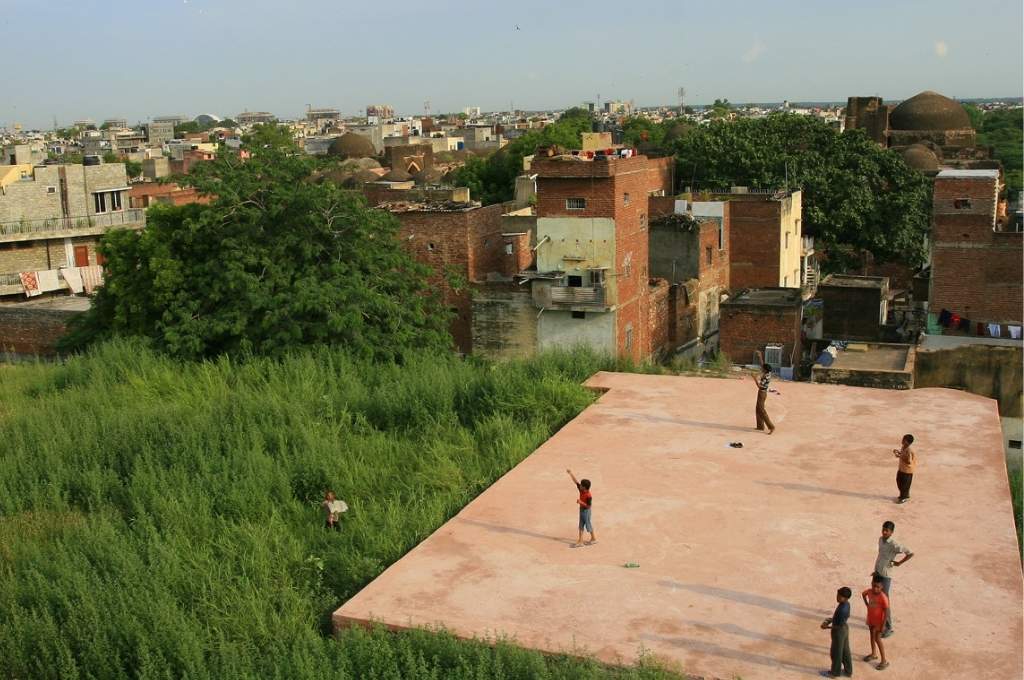

Developing cities have dense pockets of ad hoc housing and informal industrial units. As these cities matures, their single-unit, low- and mid-rise buildings are likely to be redeveloped into multi-storey tenements and formal industrial zones. Planning for this redevelopment with climate impacts in mind can help mitigate risks such as the urban heat island effect and floods. This would involve determining how much open or green space an area ought to have and what kind of building policies should guide its development. For example, city planners might decide whether all buildings should have green roofs or cool roofs to promote cooling, and what proportion of a residential or industrial compound should have grass pavers to absorb excess rainwater and mitigate heat.

2. Proactive governments

Growing cities have room to experiment and are often led by urban local bodies (ULBs) willing to adopt sustainable solutions. Officials are open to learning, and governance systems are agile enough to modify a city’s master plan to make it climate adaptive. Mira Bhayandar has a high number of open and undeveloped spaces—only 27 percent of the land area has been developed; what’s left is covered by mangroves, marshes, salt pans, forests, and hills. MBMC has yet to plan for these areas, making it easier to integrate conservation and environment-friendly solutions with the city’s development. Moreover, being a small ULB, Mira Bhayandar has fewer stakeholders within both the government and civil society contesting climate-focused development.

Additionally, as ULBs in the developing stage are in the process of drafting civic rules, they have more leeway to incentivise or enforce climate solutions. Incentives could include property tax rebates or green building certificates for new buildings to encourage the uptake of energy-and water-efficiency measures, such as cool roofs, low carbon–emitting building material, energy-efficient fans and lights, rooftop solar systems, and water harvesting pits. Alternatively, solutions like cool roofs and grass pavers could be made mandatory even as measures laid out by national-level policies such as the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016, are enforced.

3. Room to accommodate mitigation and adaption strategies

A city that hasn’t converted all its open spaces into built infrastructure can utilise them for environment-friendly solutions. Coastal cities like Mira Bhayandar, for example, can build around their water bodies and wetlands, conserving these areas as sponges and passive cooling mechanisms that can help the city adapt to the risk of floods and heat. Emerging cities can benefit from the lessons learned by flood-prone cities such as Mumbai, Bengaluru, and Chennai and design their own development blueprints with greater foresight and resilience.

There’s also scope to adopt mitigation measures at scale, such as green retrofitting. Green retrofitting involves applying sustainable technologies and innovations to conventional systems to improve their energy and water efficiency and reduce emissions. For instance, built infrastructure can be designed to include rainwater harvesting systems, grass pavers that improve permeability, energy-efficient lighting and cooling appliances, and improved ventilation. Through such targeted interventions, small but impactful measures can help manage and mitigate operational carbon emissions and promote cooling on a larger scale.

Making a CAP fit for purpose

An implementable CAP needs to accurately measure both the outcomes of development, such as per capita emissions, and the impacts of climate, such as frequency of floods and heatwave days. In practical terms, climate action planning follows these steps:

1. Climate risk assessment

The first step involves collecting data to identify areas vulnerable to climate risks. This includes information on geography, weather patterns, and land use. If the required data isn’t available, new surveys must be commissioned. For example, a city may have never conducted a hydrological survey, but increased evidence of flooding signals the need for one.

Macro and micro assessments should be carried out as well. Macro assessments include remote sensing, analysing land use and land cover (LULC) as well as Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) data on changing weather patterns, and hotspot mapping at the city level. Micro assessment involves detailed microclimate analysis, measuring parameters such as air temperature, surface temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation, wind speed and direction, and air pressure at the neighbourhood level. This data helps in devising eco-friendly interventions and providing a baseline for comparative analyses between different types of urban areas, ranging from low-rise high density to medium- or high-rise medium density neighbourhoods.

2. Baseline emissions inventory

The next step is to establish baseline measurements of GHG emissions and set up a comprehensive GHG inventory. This includes developing an understanding of how much fuel and electricity is used by different sectors—such as residential, commercial, industrial, and municipal—as well as of emissions due to water use and waste generation. A GHG inventory will help planners set a baseline and develop targeted solutions for reduction to make cities net zero through interventions like solarisation, EV buses and charging infrastructure, waste to energy plants, promoting walkable neighbourhoods to reduce use of vehicles.

3. Inclusive climate action planning

Climate action planning requires an analysis of retrospective, current, and prospective pathways to a city’s development. These pathways span a broad landscape of public and private enterprises, taking into account central-level initiatives (such as the National Clean Air Programme), state policies (such as Maharashtra’s electric vehicle policy), and private sector projects (such as tree plantation and mangrove conservation). Inclusive planning involves working with different stakeholders to develop a blueprint that addresses the identified climate risks. A robust CAP encompasses diverse mitigation and adaptation projects aimed at minimising environmental impact and enhancing resilience. In addition, it considers these projects holistically, identifying intersectional opportunities and predicting interrelated impacts when mapped on to the city’s development plan.

For example, the CAP may collectively consider the climate impact, energy security, and entrepreneurial opportunities offered by a community solar farm. Or it could weigh the costs and benefits of a tree plantation exercise that may improve the microclimate but disrupt the local ecosystem if the plant species is alien to it. Together, these initiatives form a multifaceted approach towards achieving environmental sustainability and climate resilience.

4. Project implementation

This stage involves putting the recommendations of the CAP into action. Typically, CAPs confine their scope to climate risk assessment, GHG inventories, and strategy recommendations for mitigation and adaptation. Cities could also consider implementing demonstration projects that operationalise selected recommendations. Rigorous testing in real-world scenarios facilitates a deeper understanding of the effectiveness of these recommendations and fosters a stronger, more resilient approach to sustainable urban development.

One such demonstration project at Mira Bhayandar involved green retrofitting for selected local schools to transform them into cooling centres, and retrofitting residential buildings to showcase them as models of green housing societies. The initiative aims to mitigate urban heat effects by adopting innovative techniques such as green roofs, cool roofs, water and energy efficiency measures, and solar power. A microclimate study of the neighbourhood will also be conducted to suggest context-specific retrofitting strategies and effectively guide policy development in turn.

Another demonstration project involves planting trees and increasing green cover in hotspots identified through the city’s urban heat island mapping. Creating neighbourhood sponges through nature-based solutions such as bioswales and bioretention planters, urban micro forests, green walls, grass pavers, and trees are some of the strategies that need to be integrated into city planning. In addition to reducing the urban heat island effect, these strategies also help reduce water runoff, enhance biodiversity, improve stormwater management, and create aesthetically pleasing green spaces.

How can cities improve the odds of success?

There are a few ancillary factors that need to be considered for a CAP to succeed. These include:

1. Timelines

It takes approximately eight to 10 months to prepare a CAP, but only if a ULB gathers the required data on time and processes run smoothly. However, cities may sometimes take up to two years to collect data from different departments and external agencies, by which time some of it is redundant. For example, data related to emissions depends on fuel and electricity consumption as well as waste generation, all of which changes year on year as cities grow and technologies evolve.

2. Government action

Deadlines can be met when all the departments of a ULB understand the urgency for climate action and work in tandem. This principle not only applies laterally to the local government but also vertically across the city, state, and central levels, as budgets, technologies, and incentives flow down the line. As CAPs are voluntary frameworks, their design and adoption depend wholly on the drive and enterprise of governments.

3. Capacity building

For a CAP to be effective in the long run, ULBs need to be equipped to implement it well into the future and adapt it as the need arises. This involves monitoring and evaluating the impacts of implemented solutions while identifying new vulnerabilities and risks. A CAP based on 2023 emissions data will have to reviewed periodically to understand which actions have been most effective in reducing emissions, by how much, and if the cost of the initiative was worth the benefits.

The National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA) has drafted a manual for cities on how to design a CAP and establish a climate coordination cell. However, it is primarily the city’s responsibility to proactively implement and ensure best practices, making sure it employs the right people for the job. This involves hiring qualified personnel who can effectively oversee and ensure timely execution of projects.

Capacity-building efforts should also focus on communities. These can be framed as education and awareness programmes that foster informed participation in environmental stewardship. For the Mira Bhayandar CAP, AKAH has been mobilising mahila arogya samitis—local women’s cells that lead neighbourhood health planning—to combat the effects of urban heat. In a pilot project, 15 women from a neighbourhood called Shiv Shakti Nagar have voluntarily taken on a host of responsibilities, including documenting household interest in retrofitting homes for thermal comfort, conducting audits, and overseeing the installations of retrofits such as cool roofs and green walls.

4. Finance

A CAP can cost approximately INR 50–60 lakh to develop, depending on the size of the city. The outlay covers data procurement and analysis; climate modelling; and consultations with experts in urban planning, green building design, hydrology, and so on. While smart cities and major metros find it easier to secure climate funds from national budgets and multilateral development banks (MDBs), smaller urban areas are often left to gather their own resources. Metros are prioritised for climate finance not only because their climate impacts are better known, but also because their successful climate strategies can serve as proof of concept to others.

However, if smaller urban areas are expected to finance CAPs independently, they might be resistant to it. These cities can fund climate projects through their municipal budgets, green bonds (as Ahmedabad has done), carbon credits, or philanthropy. This last option requires city officials to identify fundable projects and find the right private organisations to support it. In Mira Bhayandar, mangrove conservation is being supported by a combination of private organisations, nonprofits, and local community members.

When target areas and actions are clearly defined by the CAP, it becomes easier to identify and direct the funds to recommended projects. Every solution outlined in the CAP must be backed by budgetary estimates and proposed sources of finance.

What development organisations can do

Civil society organisations bring in technical knowledge, operational expertise, and, at times, financial resources via corporate and institutional networks to climate action planning; these may otherwise be challenging for some ULBs to access.

A development organisation typically conducts stakeholder consultations with a ULB, understands its planning priorities and limitations, and assesses the city independently to locate high climate-risk areas. It then recommends strategies based on the city’s emissions and climate vulnerabilities, prioritising measures likely to have maximum impact. For instance, to make cities like Mira Bhayandar less vulnerable to floods, drainage infrastructure supported by nature-based solutions like grass pavers, which increase the permeability of rainwater and reduce urban heat, may be prioritised over urban micro forests, which may not offer widespread absorptive benefits. Organisations offer a range of solutions to the municipal corporation, highlight their comparative advantages and costs, and recommend methods that could be implemented or formalised as policies.

India is about to witness significant urban development in the coming years, overshadowed by considerable climate disruption. Therefore, all city development must be guided by climate considerations. If we’re going to build more cities, we should build them right from the beginning. A comprehensive climate action plan is the first step in that direction, laying the foundation for resilient, future-ready urban spaces. By integrating sustainability into the core of urban planning, we can safeguard communities, drive economic growth, and contribute to global climate goals.

—