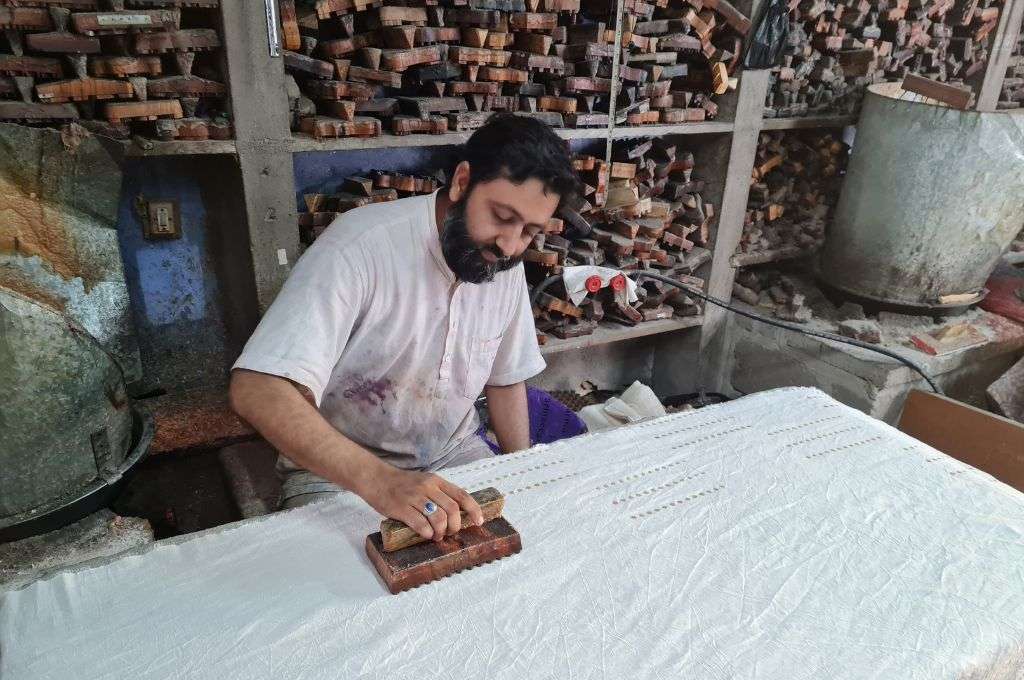

I belong to an artisan community called Khatri from Kachchh, Gujarat. My family has been producing batik—a traditional wax-resist dyeing and block-printing craft—for six generations.

Till a few decades ago, there were many batik artisans in this area. However, over the years many of them have shut down their workshops, leaving just a handful of artisans behind. There are several reasons for this. The Khatri community is very competitive—this forced many artisans to reduce the rate that they charged for their products. After a point, they could not reduce the price without compromising on quality, and so they started producing lower quality products. When this happened, eventually their customers stopped coming back, and they had to shut shop. Many workshops have closed down due to this unhealthy competition.

Another reason is that after the earthquake that hit Kachchh in 2001, a new port was built in Mundra. The government also announced a 10-year tax holiday and, as a result, many companies set up factories in this area. This created new employment opportunities. The younger generation in particular prefers these companies as they get paid a good salary to do work that is not physically taxing. Artisan-led work is labour-intensive, and this dissuades young people from choosing crafts as a career.

In addition to all of this, producing batik is an expensive affair, so anybody who wants to set up a new unit has to be ready for hard work and a high upfront cost of investment. Take for instance the fact that there has been a 25 percent increase in the cost of colour chemicals, and the price of cloth has gone up by INR 10 per metre in just one year. Batik production uses a lot of wax, which is a petroleum product. Therefore, whenever the price of petroleum increases, the price of wax also goes up. A year ago, wax cost INR 102 per kilo. Today it costs INR 135 per kilo, and a GST of 18 percent is also applicable on this. This becomes a heavy cost for us to bear.

Earlier, when there were more artisans, we had a union that received government subsidies on the purchase of wax. As our numbers reduced, the union was dissolved and now we can no longer avail of the subsidy.

A subsidy can only be demanded by a large group of artisans. However, there are very few of us left, and there is very little to no incentive for somebody new to join a competitive and labour-intensive trade such as batik. It is a bit of a catch-22 situation.

Shakil Khatri is a managing partner at Rainbow Textiles and Neel Batik, which collaborates with 200 Million Artisans, a content partner for #groundupstories on IDR.

Know more: Read about why India must empower its artisan communities.

Do more: Connect with Shakil Khatri at @shakil_ahmed_2292 to learn more about his work.