A recent report produced by Sir Partha Dasgupta for the UK government highlights the fundamental link between nature, economic prosperity, and human well-being. Simply put, ecology and economy don’t have an antagonistic relationship. Natural capital—the air we breathe, the water we drink or use to irrigate farms, the soil on which crops are sown—is the bedrock on which the entire economy is built. If we lose that, forget economic growth or the share market, the very existence of humans on earth is under threat.

Human activities have significantly contributed to the degradation of biodiversity, land, and water. And Sir Partha’s report suggests that most countries would have negative GDP growth if the depletion of natural capital was fully considered. The fundamental challenge with prevailing economic models is that they place too low a value on natural capital and thus undervalue it, which happens because we don’t quantify the ‘free’ services nature provides us.

What we measure is what we manage

So far, the valuation of nature has been the job of environmental economists. It’s not something that communities ask themselves.

This led us to wonder, what do people think about their local economies and the role of natural capital in it? What would it take for rural communities—whose very lives and livelihoods depend on the land—to measure their natural assets and make better decisions for themselves? How do people evaluate the state of the environment around them and their livelihoods, and what do they aspire for? How do they perceive risk and understand the long-term impacts of their decisions on the soil and water on which they depend?

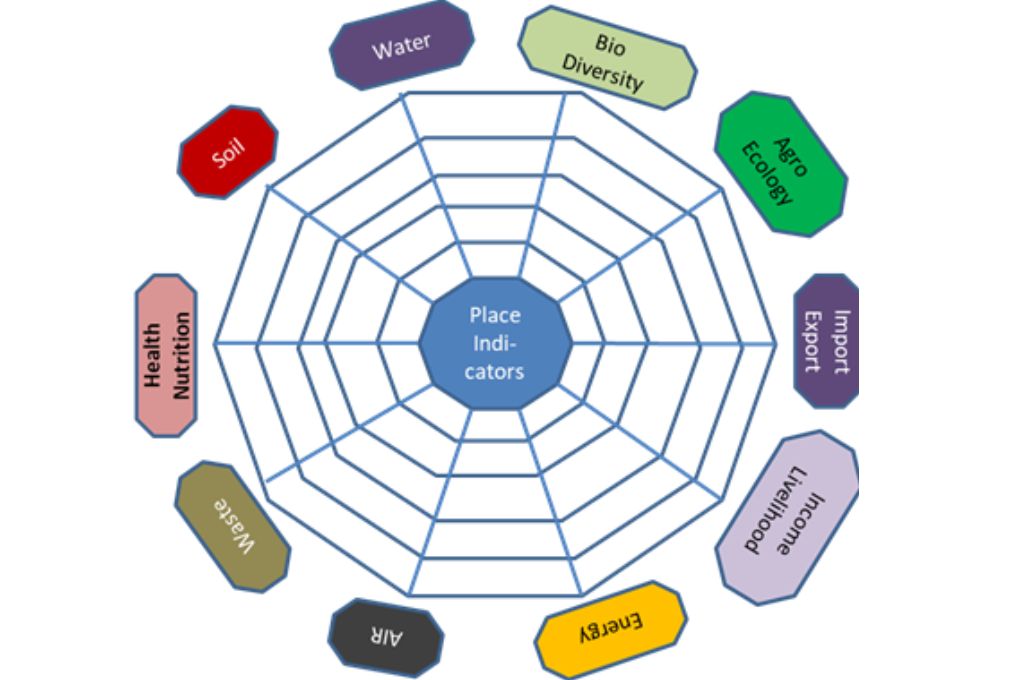

These questions help build what we call ‘a sense of the house’, which we define as a complete picture of liveability in a place and the factors that dictate it—such as income and livelihood sources; nutrition, health, and infrastructure; energy sources; the state of water, soil, and biodiversity; and waste produced. A core tenet of a sense of the house is that community members think comprehensively about their relationship with the land and own this understanding of their home. This necessarily involves measuring the different types of natural resources that people depend upon and acting upon the factors that affect the health of these resources.

Soil is only useful if the land is used to grow something. It’s inherently more personal.

We tested this on a trip to Dumaria block in Jharkhand, where we asked people to identify their most precious asset. Their first response was ‘paddy’ because that’s what they sell to earn a living. When asked where the paddy came from, they said ‘land’. We then asked them about the state of the soil’s fertility and what they would do if the land was barren, which prompted them to change their response to ‘soil’.

The discussion highlighted how land and soil are fundamentally different responses. Where land is commonly perceived as an asset that can be bought, sold, or mortgaged, soil is not. Soil is only useful if the land is used to grow something. It’s inherently more personal. This also spurred a more detailed discussion on visible signs of soil degradation and how it is affecting them. The soil in this area has become hard due to excessive use of urea. While earlier their legs would sink knee-deep into the slush when transplanting paddy, now only their feet do.

Next, we shifted our conversation to the economy: How much do people earn, what do people buy from the market, and how much do they spend? It quickly became clear that the local economy no longer produces anything that could be used by people in the area. They are dependent on selling precious natural assets for pennies to distant markets, and they are spending hard-earned cash from low-wage jobs to buy essentials from markets even when the raw materials for the things they need—food, clothing, and shelter—are present in abundance locally. Further, the economic shift has come at the cost of their natural assets, their soil and water.

A starting point for change is the community

A rural development project informed by decisions that flow down from the top is not going to work without factoring in the needs of the community. This is not a novel concept; in fact, participatory rural appraisals (PRAs) were popularised in the 1990s as an approach that incorporates the views of rural communities in projects being implemented for their benefit. PRA is a broad term that encompasses many different methods; these are unified by the common vision of “enabling local people to share, enhance, and analyse their knowledge of life and conditions, to plan and to act”.

The limitation of the PRA approach is that it was originally conceptualised to develop community consensus on the design of development programmes, so that local populations felt empowered to make demands of development institutions. Ecology and natural resources were not central to it. Communities were never challenged to think deeply about how the state of their landscape was linked to their well-being and their aspirations; rather they were encouraged to choose from a basket of preset solution choices.

Towards production systems that are cognizant of local ecological capacity

As mentioned before, a sense of the house refers to a complete picture of liveability in a place and the factors that dictate it, as perceived by the community. We want to understand whether this broad set of indicators or a scoreboard could become the default monitoring and evaluation tool. While a project-specific outlook would be pegged to a single metric, this approach is wide-ranging for it looks at the landscape as a whole, broken down into different liveability indicators that are seen as valuable by the community.

This holistic view is sometimes missing in projects being planned and implemented by both state and non-state actors. For one, a blanket directive is dangerous for a country like India that is both ecologically diverse and marked by a complex tapestry of social backgrounds, cultural contexts, and political drivers that spill over borders. When problem-solving is centralised, the focus is not on identifying which problems need to be solved but on pushing ‘solutions’ to end users. In such a scenario, when locals identify a gap that’s not in line with the mandate, they lack the agency to take action.

Take the example of giving goats to people in a place that lacks year-round fodder. On the surface, this scheme could help diversify their income sources and allow them to earn something even if crops fail. However, if the place doesn’t grow fodder crops, acquiring this input will require additional time, money, and effort. Given the top-down nature of how such schemes are implemented, there is little scope for community members to point out this gap and voice that they need additional support to sustain this new venture, or that this is not even the support they needed in the first place. They may have required improved access to water or the safety net of minimum support prices for crops that are less water-intensive.

Second, civil society organisations (CSOs) tend to approach problems with an intervention mindset. Like a hammer to a nail, most organisations might hone in on a specific problem because that is where their expertise lies. Though well-intentioned, this approach could be disconnected from the ecology and social capital of a place and lead to unintended consequences. Moreover, these organisations tend to veer towards tangible or ‘countable’ impact, like the number of check dams that were built or the number of saplings that were planted. This can be attributed, in part, to donors wanting to track where their money went.

Let’s take, for example, donor-led watershed development, which uses the metric of volume of water storage structures created. This often spurs rampant construction of structures to harvest rainwater, followed by farmers owning land close to the structures switching to water-intensive cash crops for the market. Once farmers invest in trees or polyhouses, they are locked in. Sometimes, there is an oversupply: too many farmers, for instance, could start growing chilli or cotton. With no takers for the produce, prices crash. Then in a bad rainfall year, there’s suddenly no water in the structures and the trees die, leaving the farmers in debt. The very system designed to help the community could perpetuate inequity and vulnerability.

Building a sense of the house is a big step towards allowing for a plethora of needs to be met locally. When we get a sense of the place by collating relevant data, it gives an idea of what people need, what they buy and sell, and, by extension, what props up a region’s economy. Based on this, we can graduate to looking for a solution and assessing its effectiveness not through conventional metrics such as the number of kilos of seeds provided or the number of people who opened bank accounts. Rather, success can be measured in terms of how local communities are empowered to make decisions, and how failures are treated as learning opportunities that prompt introspection and change how a programme is designed and implemented.

We urgently need a set of indicators that communities own and track over time

Our fieldwork indicates that there has been a failure to meaningfully engage with affected communities in order to build a sense of the house with them before a project is initiated. When a CSO enters a new landscape, it is important for them to understand the local context and avoid force-fitting a solution that worked elsewhere under completely different circumstances. They also need to bear in mind that this context must be owned by the community, which means the people need to understand the conditions they are in and visualise how they would like to move from this baseline to a more sustainable and prosperous future.

This requires close and constant engagement with the people and enabling them to navigate the problems to arrive at solutions themselves. Buzz Women, an organisation that works with marginalised women in rural Karnataka, uses the 5C approach, in which the focus is on personal, economic, environmental, health, and social empowerment. Their Buzz Green programme, for instance, focuses on strengthening the local economy with an emphasis on regenerative ecological principles. They first identify a ‘green motivator’ in every village; this is a woman from the community who understands the land well and will implement adaptation measures within her household and farm based on the training that Buzz Women provides her with over a course of six months. She is then able to demonstrate the benefits of these actions and mobilise other women in self-help groups.

Communities often do not see their ecological wealth as wealth.

During our fieldwork in Jharkhand, a lot of our interactive training sessions were dominated by conversations on income, even when we started talking about soil quality and access to water. We also observed that communities often do not see their ecological wealth as wealth even though income is directly dependent on the natural capital of the region. If they fail to make this connection, natural resources will continue to erode and their livelihoods will be impacted over a long term. This is why it’s important to find ways to communicate this connection effectively and reiterate that shifting to a more sustainable solution is a financially remunerative option.

They also need to be guided to make this shift in phases. But it’s difficult to communicate this in a way that resonates with local communities and prompts them to change current unsustainable practices. We are exploring ways to adopt a ‘coaching conversation’ instead of a ‘teaching’ one. A ‘teaching’ mode would lecture people: “The soil is bad; you need to take care of it.” Then there’s a ‘leading’ conversation that is more tempered in its approach: “Don’t you think the soil is bad? Should you carry out steps to fix it?” And finally, there is the ‘coaching’ method, which takes several steps back and allows people to articulate the problem themselves and arrive at appropriate solutions that they would be invested in realising: “What are the issues? What could get worse, and what can I do to fix it?”

These are, of course, ideas limited to changing mindsets and behaviours through joining visioning exercises and training workshops.

Towards a rural economy that enhances natural capital

We need a profound shift in the way we perceive and account for nature in our economic systems, but this can only happen if communities that directly depend on nature demand such a shift. For this to occur, they must first observe and document the degradation of natural capital as well as their own lives and livelihoods.

There’s no magic wand to building an alternative rural economy; it will take time and multiple iterations co-designed by various actors working together.

—