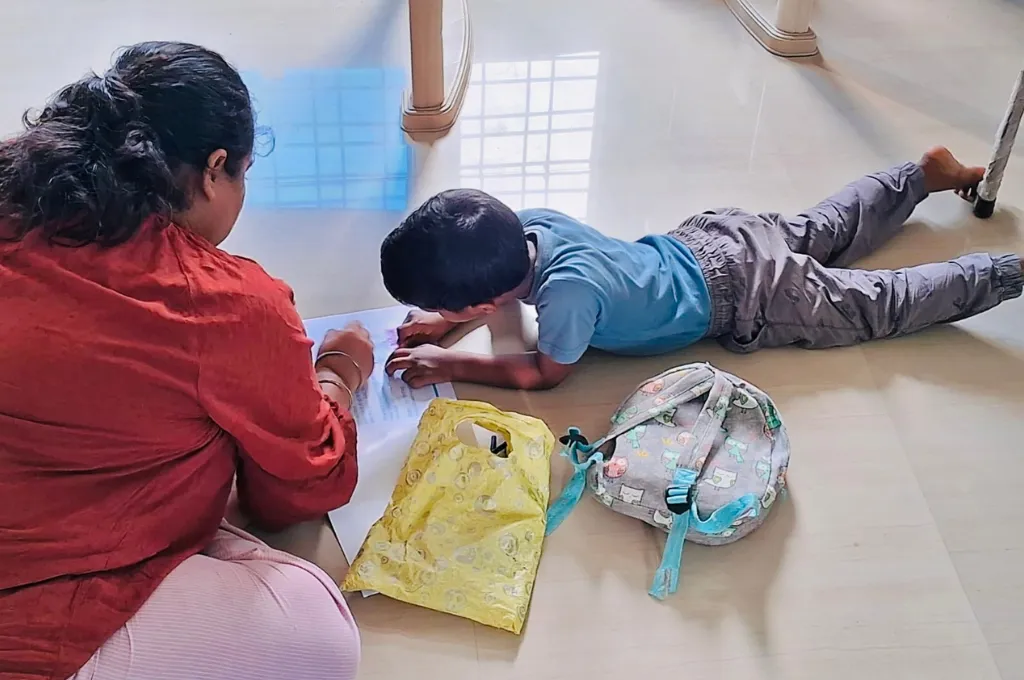

They say it takes a village to raise a child. The statement underscores the value of community and role models when it comes to a child’s social and emotional development. We saw this to be true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when homes had to be turned into makeshift classrooms, and parents and teachers had to play a more pronounced role in helping the child shift to digital learning. However, this transition was not easy. Teachers across learning levels and geographies complained of student misbehaviour and laxity during online classes.

Weak internet connectivity, interrupted electricity, outdated devices, and a lack of tech literacy were among the various issues that teachers experienced owing to their financial resources and geographical location. These situations were largely identified in schools located in rural and remote areas or government schools in cities. A survey conducted in 2020 across six Indian states found that 36 percent of teachers listed access to tech infrastructure in schools as a barrier to remote education.

The discourse around strengthening remote learning has largely been focused on students’ experiences, but teachers must also be integrated into the process. EdTech solutions have enormous potential to deliver quality at scale and contribute to a resilient education system. However, this potential can only be fully realised through the proactive participation of teachers. Bringing teachers on board requires investments in making EdTech products easy to use, affordable, and engaging.

We have solved for access. What next?

In the initial months of the pandemic, the main challenge that teachers and schools faced was around training and resources. Government schools in rural and urban India were underfunded, underequipped, and underprepared for the abrupt shift to remote learning. During the pandemic, as many as 50 percent of teachers were spending more money on teaching materials than before the schools closed. In cases where devices existed, they were not optimised for smooth connectivity.

The government and private sector were quick to act. From 2020 to 2022, the market size of EdTech products increased from USD 0.75 billion to USD 2.8 billion. This figure is estimated to grow to USD 4 billion by 2025. Public initiatives such as DIKSHA and free access to the National Digital Library, among others, provided a much-needed push. There was a 30 percent increase in screen time spent on education-related phone apps during the lockdown. Moreover, the user base for EdTech increased, particularly for the K-12 segment (primary and secondary education), which grew from 45 million to 90 million during this time.

With EdTech providers experiencing more reach, they must now focus on improving the quality of their solutions. This includes understanding local contexts, aligning with the state curriculum, and creating relevant lesson plans. The products must take a user-centric lens to increase chances of uptake. In our experience, maximising the reach of EdTech solutions among teachers hinges on getting four processes right.

1. Identifying the change agent

Community-based stakeholders such as self-help groups or anganwadi workers (AWWs) can deliver maximum impact as they have a pre-existing relationship with the local community. This is especially true in rural or low-literacy environments, where external organisations or nonprofits may be met with suspicion. India has 13.9 lakh anganwadi centres, which cater to a massive slice of the population and are crucial in driving early childhood care and education. In our experience, AWWs are curious and resourceful and enjoy close ties within the community, making them the ideal change agents.

However, including them in intervention design and implementation is not enough; organisations must earn their trust to win the vote of the larger community. For instance, Rocket Learning facilitators, who run several teacher peer groups, share daily learning activities and AWWs respond with videos of students carrying out those tasks. Play-based learning encourages proactivity and engagement from the AWWs. Tapping into the aspirations and motivations of AWWs is also key to their full involvement. Many of them want to be empowered with the resources that allow them to impart foundational learning and be taken seriously as educators. It is necessary to account for this in the programme design by including upskilling opportunities for field workers and on-ground implementers and encouraging the workers’ personal development in the process.

2. Nudging teachers towards the right behaviours

Encouraging teachers based on behavioural insights can play a key role in influencing what is happening inside classrooms. This can range from personalised assessment reports that track performance to digital badges or certifications that reward engagement. These mechanisms add a ‘human’ element to EdTech products and reinforce desirable behaviour.

Quantitative data can help draw out patterns not just to design nudges but also to optimise them.

Designing effective nudges requires substantive data, both qualitative and quantitative. Human-centred surveys and qualitative research helps root interventions in local contexts. For instance, tracking teachers’ daily, weekly, and monthly activities, priorities, and needs can help organisations identify the touchpoints to double down on.

Meanwhile, quantitative data can help draw out patterns not just to design nudges but also to optimise them. Data can allow EdTech providers to zero in on the most favoured communication channels (YouTube, WhatsApp, etc.), format (voice, text, or multimedia), or time of day, and leverage these preferences for maximum impact. Monitoring and evaluation help factor in changing patterns and update and fine-tune these over time. This encourages teachers and parents to conduct different activities with children, share proof of completion, and receive ‘rewards’ or ‘certificates’ upon achieving targets.

3. Creating holistic digital communities

Learning cannot take place in siloed teacher–student and parent–student interactions. It is necessary for teachers and parents to be in sync with the students’ learning progress and achievements, especially in a remote learning scenario where the boundaries between the classroom and home are blurred.

While setting up digital communities, low-capacity settings are ideal to utilise existing structures. Used by more than half of the students and 89 percent of teachers, WhatsApp, for instance, emerged as the most popular channel of communication. Designing simple solutions that build on top of these patterns make them cost-effective and increase the likelihood of participation. It is also especially beneficial for parents who depend on daily-wage labour and cannot skip work to attend physical meetings.

Creating a constant feedback loop between teachers and parents is effective in helping establish positive parent–teacher, teacher–supervisor, and teacher–child relations. This also creates a supportive community that parents and teachers can lean into to share their concerns and vision for the child’s learning journey.

4. Working effectively with governments

Working with governments is the best way to deliver impact at scale. Market-driven EdTech solutions tend to prioritise users who can afford to pay for their products. Meanwhile, organisations looking to deliver services to marginalised communities often face resource limitations. Government support can bridge this gap between intention and impact, ensuring fairness in terms of student usage, learning activities, and teacher training. Having said that, it can be time-consuming to ensure state willingness and capacity to roll out such programmes at scale. Moreover, EdTech organisations seeking to implement solutions in government schools have to contend with formal rules and informal practices that vary from state to state. Integrating the hardware, product, and lesson plans into the existing public school ecosystem often requires approvals and negotiations at multiple levels.

Organisations and governments working in these spaces must project teachers as the face of the intervention.

Aligning with state priorities and designing focused interventions across the governance hierarchy—from the anganwadi teacher and their supervisor to the project-, district-, and state-level officials—is critical to keeping the system engaged. Additionally, organisations cannot copy-paste intervention templates that worked in one state or district on to another. It is necessary to gauge the motivations and priorities of each administration before formulating an approach. Recognising the unique needs and operating environment of the state to tailor the plan is a vital step in ensuring meaningful engagement.

Ensuring EdTech uptake among teachers in rural areas with no experience or tech receptiveness is challenging but necessary. The World Bank’s EdTech Readiness Index recognises this, listing teachers as one of the six pillars to be strengthened for best practices in policy and application. Prioritising teachers’ motivations and attitudes, and pushing for a broader mindset shift, will play a major role here.

Most importantly, it is necessary to dispel fear and suspicion around tech. EdTech services should not be presented as a replacement for teachers, but as a resource that complements their work and helps ease their burden. Organisations and governments working in these spaces must project teachers as the face of the intervention as much as possible. Only through educator buy-in and engagement can we tap into the full power of EdTech to transform students’ lives and work towards building a resilient education ecosystem.

In order to build and sustain teachers’ engagement, it is imperative to position technology and EdTech as tools that can build and further augment teacher capacity. We need to leverage data from such solutions to build positive loops in terms of teacher behaviour and be cognisant of region-specific nuances for the design-to-implementation journey of EdTech solutions.

—