The Indian government has actively pursued policies to increase the female labour/workforce participation (FLWP) rate in the country for several decades. Their approach has evolved from educational scholarships, reservations, and quotas, to self-employment through self-help groups (SHGs), and more recently to capacity building through skill training programmes.

Yet FLWP has been on a downward trend. Labour bureau data shows that FLWP fell by 7 million between 2013-2015, and as per the latest NSSO PLFS survey 2017-2018, only 17.5 percent of women are part of the labour force, compared to 55.5 percent of men.

Only 17.5 percent of women are part of the labour force, compared to 55.5 percent of men.

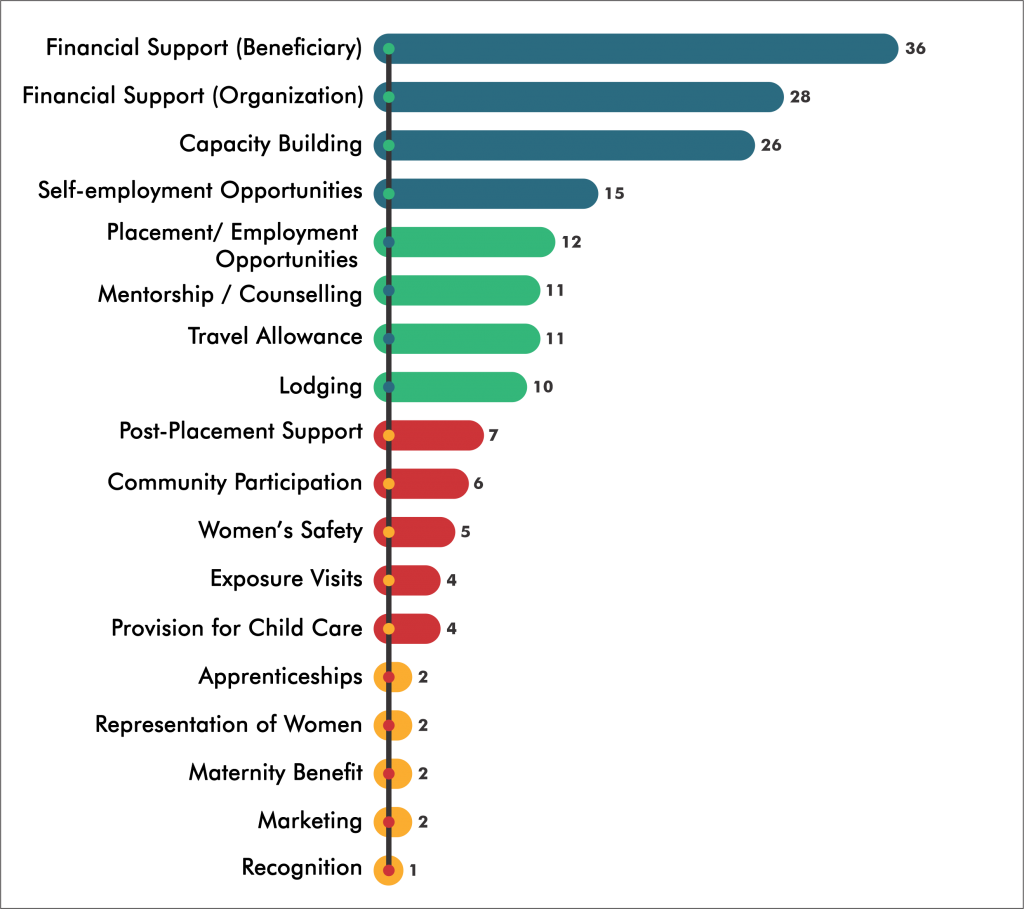

In our study—Female Work and Labour Force Participation in India—to understand the current policy landscape, a database of 53 legislations and policies was created, through a review of the 2018-2019 budget and government repositories. It documents the policies’ gender focus, targeting strategies, inclusion mechanisms, eligibility criteria, and geographic focus, among other indicators. The database also registers whether the following programme components were present or absent in each policy:

While the success of female entrepreneurship programmes and the SHG movement have helped policymakers recognise the potential that women have to further India’s economic growth, women-oriented policies need more thought.

Related article: Women’s workforce participation: What we need to know

Is financial assistance enough?

Whether in the form of stipends, cash transfers, fee waivers, or scholarships—financial support seems to be the most commonly occurring programme component. And there are almost 25 such government run programmes.

Fewer schemes tackle the social and familial barriers that prevent women from participating in the labour force.

Despite the widespread acknowledgement of the need to ease the burden of the care economy on women, relatively fewer schemes tackle the social and familial barriers that prevent women from participating in the labour force. There is a lack of public safety, workplace security initiatives, and safe transportation; not only are these unavailable in standalone schemes, they are barely present as policy components within existing capacity building and livelihoods initiatives. Other pivotal factors, like childcare facilities within skilling initiatives (important for young mothers interested in these programmes) are also seen to be missing from most initiatives.

Further, while these skilling courses necessitate counselling of some form, career guidance and mentorship support are a rarity. In contrast, empirical work in this area has found strong evidence to suggest that labour market information, mentorship, peer-effects and improving women’s self-efficacy are significant channels to improve labour participation.

There is a lack of public safety, workplace security initiatives, and safe transportation, and other pivotal factors like childcare facilities are missing within skilling initiatives | Picture courtesy: Wikimedia Commons

Evaluations of skilling programs have found post-placement retention for women to be worse than men. ‘Personal’ challenges are often cited as the reason to discontinue work by these women. There is a dire need to effectively operationalise counselling provisions within these schemes, and ensure that women are able to access them during, before, and after the programme. Evidence from other countries shows that there is substantial uptake of skilling initiatives when women are offered the course within their village. Similarly, research from India, has shown that in the effort to minimise risk of harassment in transit, women often make qualitative compromises in their educational choices.

Are the policies designed to be inclusive?

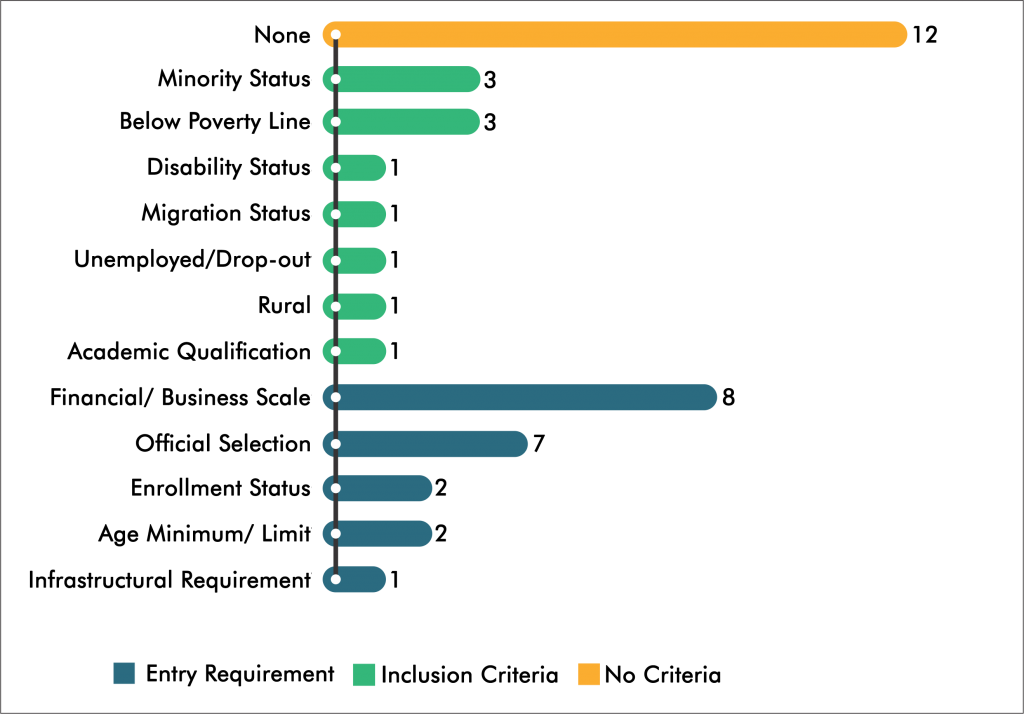

Given that various factors intersect to form a person’s identity, and that social or economic factors can further accentuate the burdens imposed by gender, policies must recognise that some women are more prone to exclusion than others, and need to work to counter this. A significant number of schemes ‘encourage’ inclusivity as a policy mandate, without actively designing for this.

Only 10 policies were found to have inclusion criteria such as minority status, drop out status, and disability status, among others. Generally, policies are more likely to have exclusion criteria such as academic qualification or age limit.

Blanket allocations without a thorough road map that recognises the contextual realities of marginalised women are likely to yield suboptimal results. For example, Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY) offers post-placement support of INR1,450 per month1 for special groups (comprising women, persons with disabilities, and candidates in special areas). However, by lumping them together into ‘special groups’, this policy feature does not factor in the widely different needs of the people within these groups.

Related article: Women, work, and migration

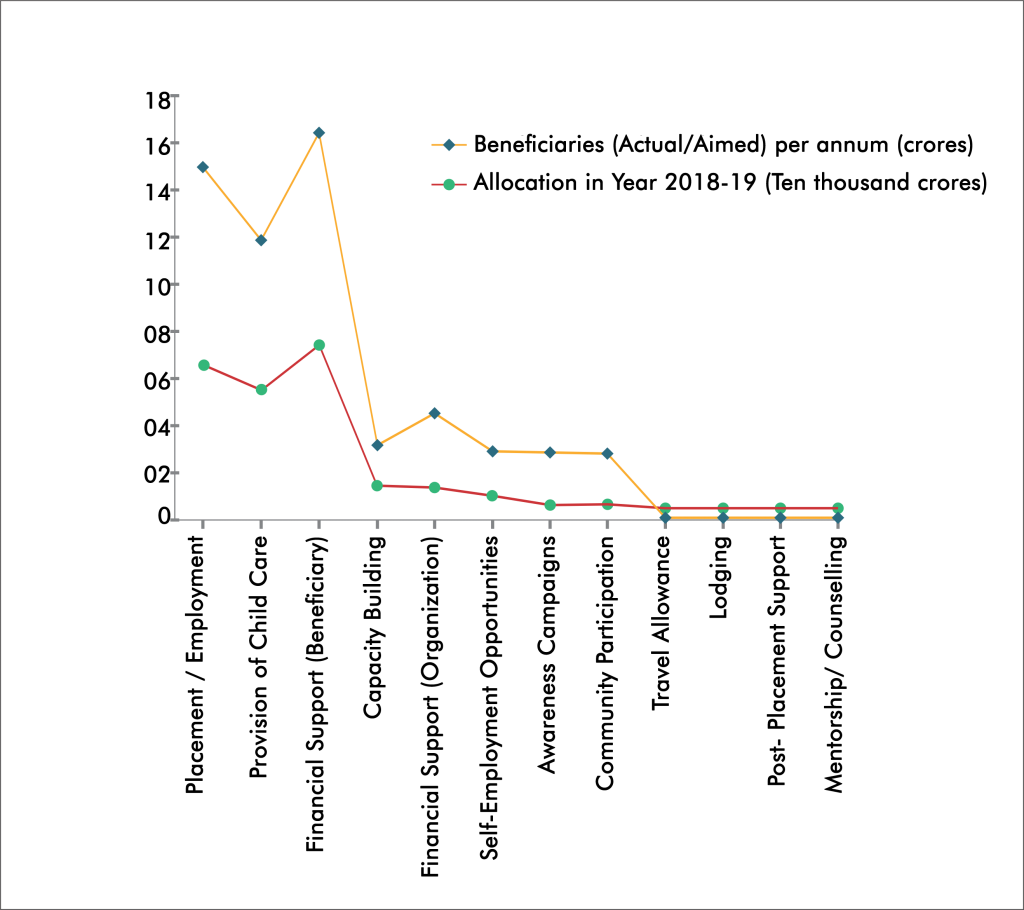

What implications does a focus on quantifiable outcomes have?

Barring a few programmes like the National Creche Scheme, it is evident that current policy prioritisation is motivated more by quantifiable outcomes, such as placements and skill certification. Yet skill improvement does not necessarily lead to higher participation or even higher wages. For instance, when women in a garment factory in Bangalore were given on-the-job skills training, their productivity increased and net returns of the firm rose by 258 percent, however there was little impact on their wage levels as a result of (downward) wage-adjustments by the firm.

Skill improvement does not necessarily lead to higher participation or even higher wages.

The inordinate focus on quantifiable outcomes often proves to be counterintuitive, and likely to perpetuate exclusion. Consider, for instance, the Deen Dayal Upadhyaya Grameen Kaushalya Yojana (DDU-GKY). In order to recover the full cost of training, skilling agencies are required to ensure a 70 percent placement target. This means that the programme is more likely to be biased to select those candidates who are already pre-disposed to being placed; in other words, those who are more employable all along. Because of the scheme’s compliance mandate, those who could benefit most from the programme might be excluded.

This is why, there is growing evidence to suggest that vocational training needs to be part of an amalgam of several policy components for the training to have an impact on employability. In almost all the successful cases, training was accompanied by recruitment services, literacy camps, adult education and more.

Better policy design is the need of the hour

Despite the gamut of labour market policies operating in India at a national and state level, policy research on female labour-force participation is constrained by the unavailability of national statistics and policy evaluations at an outcome and impact level. This in turn adversely affects policy design which loses its focus on inclusive outcomes and instead focuses on achieving target number of beneficiaries or services.

Research on female labour-force participation is constrained by the unavailability of national statistics and policy evaluations.

The practice of quantitative and qualitative impact evaluations must be institutionalised. Government commissioned assessments have been sporadic and conducted using incomparable methodologies and frameworks. For example, currently some labour market schemes are not independently evaluated even if they do have budgetary provisions for them (eg. PMKVY and DDU GKY), others may not have budgetary provisions (eg. Rajiv Gandhi Crèche Scheme), and still others may not be published online even when evaluated (eg. NSDC STAR Scheme).

Defining the right metrics which help understand the various dimensions of female workforce participation, measuring them regularly as part of national databases and impact evaluations and publishing them transparently in order to constructively feedback into policy is necessary if India is to achieve gender parity in the workforce.

—

This interactive policy dashboard deconstructs gender and employment related policies, and identifies gaps and opportunities which can be leveraged to increase the workforce participation of women in India.

- At the most, two months for men, and three months for women.