A recent article on outcomes-based financing (OBF) in education posed a critical question: When success in education is measured by outcomes, who gets left out of these success stories? As someone working on OBF for education, I recognise this challenge. OBF—tying funding to results rather than inputs—has driven notable gains in learning and enrolment. Yet it often lacks an explicit focus on equity.

The good news is that we can refine OBF models to be more inclusive. By adjusting how we design and incentivise these programmes, we can ensure that every learner—and not just the easiest to reach—benefit from them. In fact, OBF’s data-driven nature can help pinpoint who is being left behind and test solutions to support them. But for this to happen, funders must actively prioritise inclusion and think beyond overall success.

The equalising power of an outcomes focus

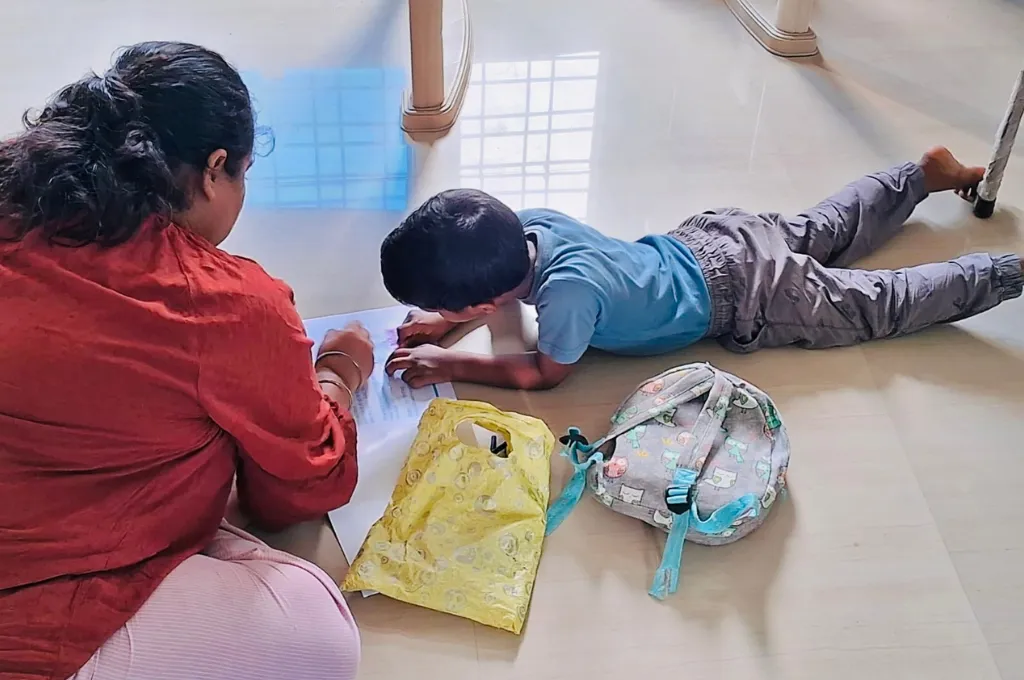

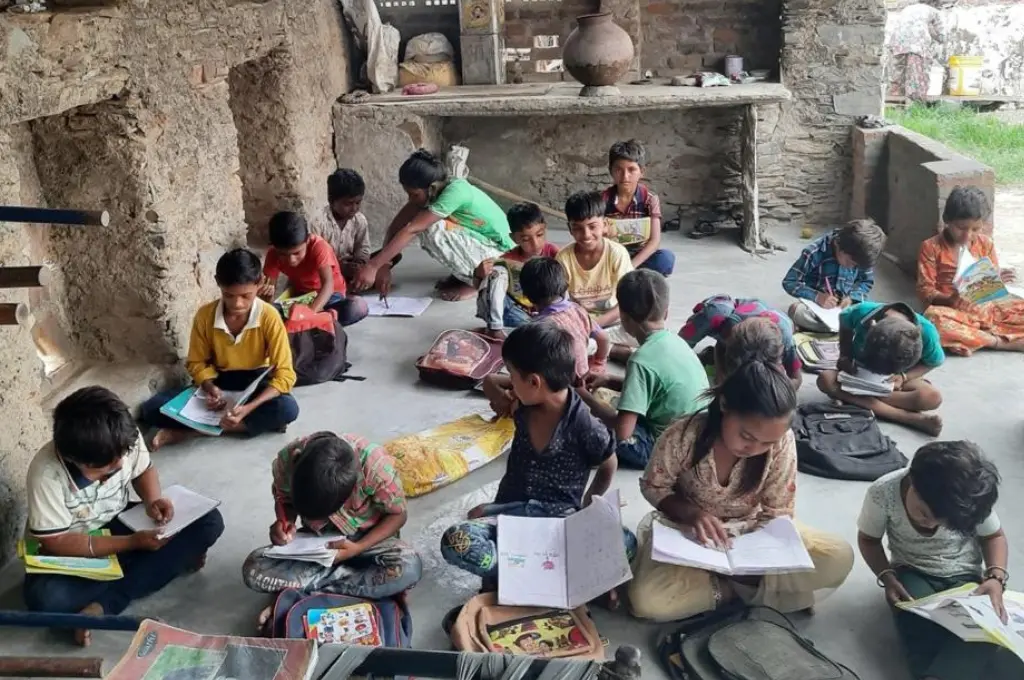

Based on my observations of OBF projects in India, even without an explicit inclusion mandate, such initiatives often end up benefiting marginalised groups. Improving an average score usually means helping the children whose scores are the lowest.

However, there are structural issues at play here. In many Indian classrooms, for example, basic skills are alarmingly low—in rural India, only about half of fifth graders can read a simple second-grade text or do two-digit subtraction. An intervention rewarded solely on average test scores can’t succeed unless it boosts the learning of these large groups of children who are lagging behind.

That said, OBF often uncovers barriers that had gone unnoticed. Take the Educate Girls Development Impact Bond (DIB) in Rajasthan for example. Monitoring revealed that some students weren’t performing well because they couldn’t see the blackboard. A pilot vision screening found that 25 percent of the 1,000 children screened had eyesight problems. Once given eyeglasses, the children’s ability to learn improved markedly. So by incentivising overall improvement, OBF can push implementers to address the needs of struggling students, whether through remedial action or simple solutions like glasses.

But relying on OBF’s trickle-down inclusion by accident is not enough. Yes, a rising tide can lift all boats—but only if every boat is given the support it needs to stay afloat. In its current form, OBF risks leaving the most marginalised learners struggling against the current.

When ‘what works’ leaves some behind

The core issue is that OBF is typically agnostic about who improves. Driven by financial incentives, implementers will naturally gravitate to strategies that yield the biggest impact with the least effort. Often, helping moderately behind students catch up is cheaper and faster than dedicating resources to children with severe learning disabilities or those facing multiple barriers. OBF models don’t inherently discriminate, but they are not inherently inclusive either. Any inclusion that happens is a by-product rather than an intentional design feature.

Consider a child with a learning disability, or one who speaks a minority or tribal language. Teaching them to read might require a specialised educator, adaptive curriculum, or assistive technology. All of that takes resources—potentially far more than what it would take to improve the learning level of a child without those challenges. For example, according to one estimate, the overall cost of educating a child with disabilities in developing countries is approximately 2.3 times higher than that of educating a child without disabilities. Yet, a typical outcomes contract might treat both children’s learning outcomes as equal. If it costs more than double to truly include a child with disabilities, but the contract does not provide commensurate compensation, service providers have a financial disincentive to work with that child.

This misalignment is what the rights-based critique to OBF highlights. When success is measured by aggregate gains, it’s possible to meet the target while skimming over those who need the most help. In the worst cases, an average-based OBF contract could even encourage schools to avoid enrolling children with disabilities or learning lags, in order to prevent dragging down the metrics. Without deliberate safeguards, efficiency can trump equity. To truly leave no child behind, we must build inclusion into the design of OBF instruments, not assume that it will happen on its own.

Designing OBF for inclusion: Five key levers

1. Target marginalised groups directly

One approach is to make the target population of an OBF programme a disadvantaged group. The UK’s Fair Chance Fund did exactly this: it was a three-year social impact bond (2015–2017) aimed exclusively at homeless youth to improve their housing, education, and employment outcomes. In India, the Skill India Impact Bond mandated that at least 60 percent of those targeted must be women. These quotas ensure that implementers focus on marginalised communities from the outset rather than as an afterthought.

2. Use differentiated payments for harder outcomes

Not all outcomes are created equal—some are harder to achieve, often because they involve deeper barriers. OBF contracts can be structured to pay more for outcomes that require more effort. The Educate Girls DIB allocated 20 percent of payments specifically for enrolling out-of-school girls. The Chicago Parent-Child Center Pay-for-Success contract assigned much higher payouts to certain outcomes: Each child who did not need special education services later in school earned USD 9,100 for the investors, whereas each child who achieved kindergarten readiness earned USD 2,900. By valuing harder-to-achieve outcomes higher, these programmes ensure inclusion is financially viable.

3. Build flexibility to adjust mid-course

Marginalised sub-groups may not always be pre-identified—for instance, only during the execution stage of a programme might it become clear that Adivasi students who speak a non-mainstream or minority language in a particular district are disproportionately struggling. Traditional contracts can be rigid, but OBF mechanisms can adapt in response to new data. For example, an education impact bond could allow reallocation of funds if monitoring data shows that a particular group is falling behind. This reserved pool of funding could activate proven solutions, such as hiring local language tutors. Some OBF structures, like the Fair Chance Fund, have mitigated cherry-picking by ensuring high-need referrals are prioritised rather than left out of performance incentives.

4. Reward intersectional impact

Marginalisation is often multi-layered. A child might be disadvantaged because they belong to a low-income household, is also a girl, additionally belongs to a discriminated caste, and has a disability as well. Instead of treating gender, disability, and socio-economic status separately, OBF can incentivise tackling multiple barriers at once. Rather than just paying for girls’ learning outcomes and separately rewarding children with disabilities’ learning outcomes, an outcomes funder could pay extra for each girl with a disability who reaches a certain learning level. This approach ensures that those facing compounding disadvantages are not overlooked.

5. Blend finance with capacity building for inclusion

Money alone doesn’t guarantee that organisations can deliver inclusive education—they also need the know-how, tools, and capacity. A promising trend is the emergence of consortium-based OBF initiatives like LiftEd. These combine multiple implementing partners and even multiple instruments under a common umbrella to foster learning exchange while working towards a common set of outcomes (for example, foundational learning). Such platforms can provide an efficient and scalable way to ‘top up’, or provide additional support and resources on top of the core OBF structure, by embedding an inclusion lens. Funders can provide parallel technical assistance grants to build service providers’ capacity for inclusive delivery in such consortium set-ups.

Embracing complexity for equity

We now know how to make OBF more inclusive. The tools exist, the case studies are growing, and the mechanisms have been tested. But making OBF more inclusive adds layers of complexity to measurement, performance management, and payment tracking. While it is tempting to simplify financing structures, doing so risks overlooking those who need the most support. Funders must prioritise inclusion in their financing models—whether by structuring contracts to reward equity, embedding technical support, or setting clear expectations that success means everyone moves forward.

The next generation of OBF contracts must reflect this shift. The future of education finance is not just about measuring outcomes—it’s also about ensuring that every child, regardless of their starting point, has a fair shot at success. By embracing the complexity needed to drive real inclusion, funders can turn good intentions into lasting, equitable impact.

—