Common lands–whether the shamlat lands of Rajasthan, sarbasadharan in Odisha or poramboke in Tamil Nadu–are natural resources that are used collectively by a village community. Taken all together, common lands such as community forests, pastures and wastelands cover nearly one-fourth of the Indian territory (Chopra and Gulati 2001). These resources sustain the lives and livelihoods of more than 350 million rural poor in India, who rely on them for fodder, fuel, forest produce, fish, bamboo and much more.

Despite this, India’s commons are routinely marginalised. The predisposition towards private property, improper demarcation of common land boundaries, vague legal classifications, disarray of applicable legal regimes and lack of formal tenure to the communities that depend on them, have since long been issues that commons have been afflicted with. Usually, this leads to two outcomes: commons either get formally diverted towards more ‘productive’ and ad-hoc uses, or get encroached by private individuals for their personal gain.

Architecture for protection of the commons

During the process of land settlement in the country, while individuals were provided rights to the private lands, common lands were largely brought under state control through eminent domain1 (Ramanathan 2009). A better part of this was, and is still, erroneously regarded as ‘wastelands’ (Singh 2013). Even so, these lands fall under the purview of Article 39(b) of the Constitution of India, which states that the “ownership and control of the material resources of the community” should be distributed to “best subserve the common good”. While this directive is not enforceable or justiciable, it is a moral imperative for our policies and embodies the idea of India as a welfare state. Commons further draw strength from judicial verdicts that uphold the Public Trust doctrine, where the State is regarded not an absolute owner but a mere trustee of all natural resources for the benefit of the public at large. Progressive judicial orders such as Jagpal Singh & Others versus State of Punjab & Others (2011) also re-assert the communities’ rights over their commons.

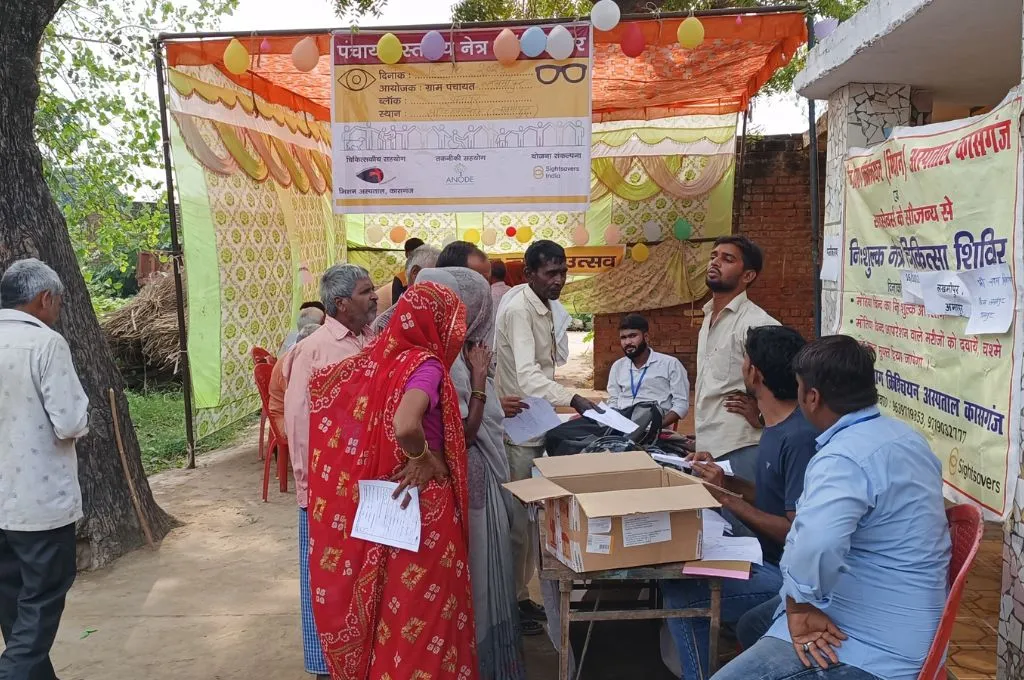

For land management, common lands largely fall under the jurisdiction of the state revenue department and the forest department. However, after the 73rd Constitutional Amendment, the panchayats received custodial rights to protect and govern village common lands. Subjects like land improvement, water management, watershed development, social welfare and maintenance of community assets were also entrusted with the Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs). Yet, the architecture and the tools that can enable, support and empower panchayats in this endeavour need our attention.

What is an asset register?

In its simplest form, an asset register is a detailed list of all assets held by institutions. Its purpose is to enable institutions to know the status, condition, location, price, depreciation, and the current value of each asset. These registers help to identify assets, prevent asset loss or theft and, if maintained well, can provide an accurate audit trail (Kumar and Paul 2017). As a whole, asset registers can play a pivotal role in ensuring transparency, reducing the risks of corruption and laying the foundation for political accountability. However, preparing asset registers also brings along with it the need for processes to ensure their proper upkeep, maintenance and compliance with regulatory standards. This usually requires conducting a physical audit or social audit to safeguard the assets against misuse or misappropriation.

The responsibility to maintain asset registers and to update them regularly has been conferred to the gram panchayats.2 However, while the panchayats’ role has been laid out explicitly, little has been done to ensure that they have the knowledge or the capacity to implement it in good faith. Experiences from the ground reveal a lack of awareness, uncertainty, and even apprehension over what asset documentation entails. Although formats for asset registers are usually prescribed by states, the procedure frequently casts a doubt on the kinds of ‘immovable assets’ that are to be entered, to whom they rightfully belong to, or how they are to be maintained or monitored. In most cases, panchayats approximate by maintaining a list of fixed and movable assets under their ownership, such as buildings or office furniture, and fail to enter or update the records with all land and water resources they are meant to manage.

Issues with data and decentralisation

In India, the Tragedy of the Commons (see Robinson 2021) is not just because communities have been unable to organise themselves, but equally culpable is the lack of enabling infrastructure to catalyse community action. The real ‘tragedy’ is that, while panchayats have been given the custodianship to manage the commons, the details of this custodianship are not maintained nor made available to them at their level. The siloed functioning of each agency, like the revenue or forest department or the panchayats themselves, along with their competing interests and lack of convergence in their roles, makes it even more difficult to manage the resources. This is further exacerbated by the lack of, or difficulty in accessing the data about the common lands that are used by the village community; customary tenure to such resources has not been included in the Digital India Land Records Modernisation Programme (Gurumurthy et al. 2022).

Making data accessible and digitally available, especially in spatial formats, through open-data registries may enable better governance. Entering common assets like grazing lands, forest lands or lands meant for development purposes, as well as the resources being developed under various programmes (especially the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme), could thus go a long way in managing and protecting these resources as well as designing programmatic investments for their development.

Land audits as a solution

Building access to information is only half the solution. Regular land and social audits need to be conducted to ensure that panchayats properly and efficiently maintain asset registers. In the recent past, land audits or performance audits on land management have been a common state practice within urban areas. For instance, the Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India conducted a performance audit on land management by the Delhi Development Authority in 2014, while the Mysuru Urban Development Authority undertook a land audit in 2022 to identify encroached lands and to reclaim their possession. Occasionally, land audits have also been conducted in rural areas, such as in 2017, when the Punjab government audited 12,500 panchayats where land sharks had usurped panchayat lands and were pocketing the income they generated.

The examples cited above provide sufficient reason for audits on land management to be a regular feature. Given the widespread dependence of several stakeholders on commons, mechanisms to scrutinise and monitor land governance in rural areas need to evolve. Not only would this help identify and remove encroachments, it would also measure the adequacy and effectiveness of governance practices. This could further enable better investments in the restoration and upkeep of such resources.

In November 2021, the CAG issued guidelines for financial audit of PRIs, which included substantive checking of immovable asset registers under its scope. The CAG reviewed the identification of assets through geotagging, photographs, etc., the accuracy of the value recorded in the register, reporting of encroachments; and traced its expenditure under different schemes in different years.

While this is a significant step, the framework of audits should be expanded to include and assess the following aspects:

- Whether there is a proper demarcation of the land parcels; and whether an effective system of records management and documentation exists.

- Whether there is misuse or encroachment on the land; and whether action has been taken for their removal in accordance with the due process of law.

- Whether an efficient planning, control and monitoring mechanism for carrying out the land management activities is in place and is functional.

- Whether restoration/management activities are being executed with efficiency, economy and effectiveness.

When the panchayats realise their responsibility as custodians of the common lands, and the instrument of asset registers as well as routine audits are in place, encroachment could reduce, and better governance of resources can be brought about.

—

Footnotes:

- Eminent domain is the power of a government to take private land or property for public use.

- For instance, Rule 36 of the Odisha Gram Panchayat Rules, 2014; Rule 137 of the Rajasthan Panchayati Raj Rules, 1996; Rule 20 of Goa Panchayats (Accounts, Audit and Custody of Funds) Rules, 1997; etc. enable this action.

This article was originally published on Ideas for India.