Article 21-A of the Indian Constitution guarantees the fundamental right to free and compulsory education for all children aged six to 14 years. The Right to Education Act (RTE), 2005, turned this right into law. But what happens to those between the ages of 14 and 18? ASER 2023 focused on 14- to 18-year-olds in rural India to not only ascertain whether the youth possessed foundational skills, but also provide insights into their activities, ability, awareness, and aspirations. This age group comprises those who have already received eight years of guaranteed elementary education.

The findings, which were collected from 35,000 children across 28 districts in 26 Indian states, were based on these four domains. Additionally, the study included a series of qualitative interviews conducted in Sitapur (Uttar Pradesh), Solan (Himachal Pradesh), and Dhamtari (Chhattisgarh), which delved deeper into the aspirations of the youth.

Education doesn’t automatically translate into increased ability

The report shows that overall, approximately 87 percent of the surveyed youth are enrolled in some kind of educational institution. The ratio of school and college dropouts has reduced over the years, with more young people completing senior secondary school than ever before. But when those who are not enrolled were asked why they discontinued their studies, the most commonly cited reason at 18.9 percent was ‘lack of interest’. Financial concerns, family constraints, failing to pass exams, and other challenges fell lower on the scale. Interestingly, 26 percent of those not enrolled in any educational institution reported that they used their smartphones regularly for some educational activity, such as watching online videos, exchanging notes, and resolving doubts.

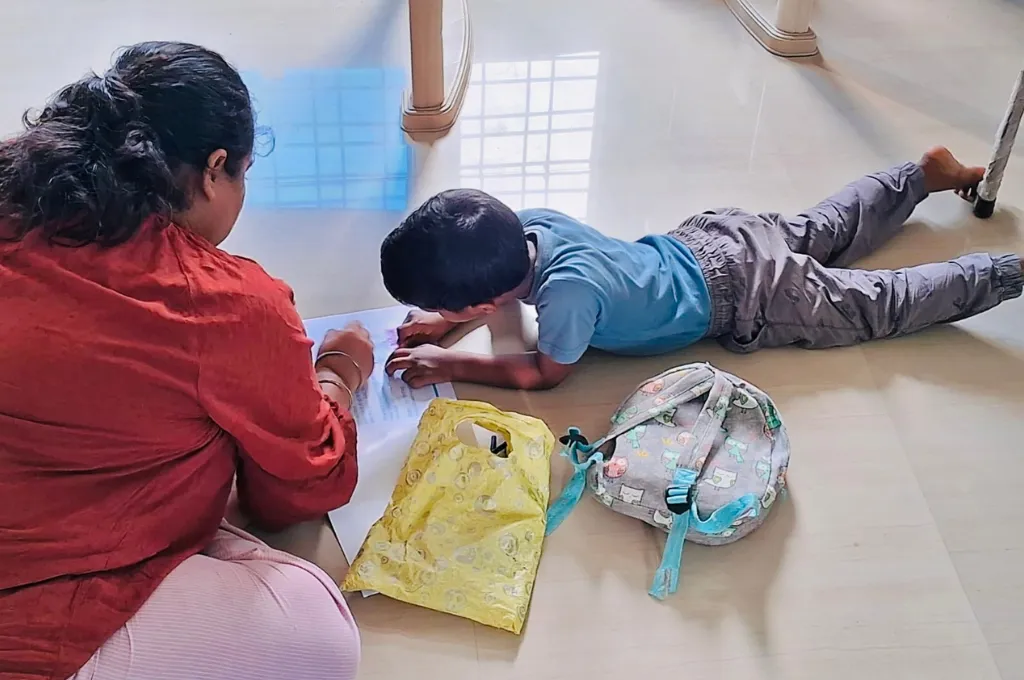

“We can learn how to manage a household, how to talk to others, how to present ourselves, and how to respect the people around us,” a girl in class 10 from Sitapur responded when asked about the benefits of education.

For an age group that is expected to learn trigonometry and calculus as per the curriculum, only 43 percent could solve basic division problems.

However, it appears that years of schooling do not necessarily translate into proportional levels of learning. Approximately 75 percent could read a class 2 level text in their regional language and 57 percent could read simple texts in English. For an age group that is expected to learn trigonometry and calculus as per the curriculum, only 43 percent could solve basic division problems, and 10 percent could calculate simple interest on loans.

The current system doesn’t appear to account for the socio-economic background of a learner. Many of the youngsters reported that they have to work while pursuing education. Approximately 77 percent of the youth surveyed do some form of household work. Of the 34 percent who reported engaging in some form of paid work for more than 15 days in a month, 85 percent participate in agricultural work. The education system doesn’t reward children who work—rather, there’s a higher probability that their performance at school declines due to the increased workload that comes in secondary school.

Most of these findings align with those observed in ASER 2017. However, since digital access was increasingly incorporated in education during and post the pandemic, ASER 2023 added a digital skills assessment component, wherein youth were asked to attempt basic tasks using a smartphone. The test offers a clearer insight into the way technology has fundamentally changed the way youth are learning and thinking about their future.

Digital literacy is not the problem

Over the past few years, there has been a steady increase in smartphone penetration in India. True to this trend, ASER 2023 observed that 90 percent of the adolescents surveyed had access to a smartphone and 67.1 percent of the total sample were able to produce a smartphone during the survey itself (others indicated that the smartphone was with a parent/sibling who wasn’t present at home during the survey). Approximately 92 percent of those who were able to produce a smartphone during the survey were able to complete the digital tasks successfully on the following aspects.

1. Ease of usability

Approximately 80 percent of young people who possess smartphones are capable of locating a particular video on YouTube, and of this group, 90 percent know how to share it with a friend. In addition, 70 percent can navigate the internet to seek answers to inquiries, while close to two-thirds are able to set an alarm for specific times. A little more than one-third can use Google Maps to ascertain the duration of travel between two destinations.

During these digital assessments, boys tended to perform better than girls in most tasks. However, the primary factor in this case appeared to be smartphone ownership. Among those who knew how to use smartphones, 43.7 percent boys and 19.8 percent girls actually owned the smartphone. When the differences in ownership disappear, so does the difference in digital skills between boys and girls. Computer ownership was found to be far lower than smartphones (less than 10 percent), but there were similar trends in digital skill patterns. Digital literacy is directly proportional to increased access to devices.

2. Tech for creativity and life skills

The survey clearly indicated that young people look at technology as a pathway for creative expression. Approximately 78 percent use their smartphones for entertainment-related activities such as watching movies or listening to music, 57 percent play games regularly, and 90 percent had used some form of social media in the previous week.

“With a phone in our hands, we can learn anything without having to spend money or ask anyone [for permission],” Shristhi Sandhil, an 18-year-old from Jharkhand, said as she talked about how she uses YouTube for learning new creative skills. This sentiment was echoed by many, who highlighted that it was the freedom afforded by the smartphone that made them turn to it.

The smartphone has enabled wider skill acquisition by cutting across barriers of access and opportunity. More than 35 percent of the youth reported using their smartphone to engage in dance, music, photography, and other hobbies.

Given the increased use of technology, including for creative expression, it is important to acknowledge that what was once an extra-curricular might have to become a part of the core of the curriculum. While creativity has a significant place in the cultural context of Indian communities and despite its recognition as a key twenty-first century skill, it is yet to be brought to life in a tangible manner by the education system. Through games, projects, activities, and other forms of interactive learning approaches enabled by technology, creativity needs to become a core facet of academic learning.

Young peoples’ aspirations tell a story

When asked about their aspirations, there were clear patterns across states and genders. For instance, in terms of career aspirations, while ‘nursing’ was the top voted choice in Kerala for girls, it was ‘teaching’ in Rajasthan, ‘doctor’ in Jammu and Kashmir, and ‘police’ in Maharashtra. Similarly, boys in Assam chose ‘army’, those in Tamil Nadu chose ‘engineering’, and in Chhattisgarh it was ‘agriculture’. While girls indicate a stronger aspiration for higher education, boys appeared to prioritise income generation as they plan their careers.

A boy studying in class 10 in Dhamtari told us, “I will become famous and gain respect in the community—there’s a boy from the village went into the army. My father had failed high school, but because of this [his son joining the army] he will also gain recognition. I will get money as well. And I will be able to protect the country.”

Both boys and girls indicated that social responsibilities would ultimately shape their decisions.

But what was concerning is that approximately 1 in 5 youth surveyed said that they did not know what they wished to pursue. Of the ones who indicated preference for a particular kind of work, 45 percent indicated that they didn’t know anyone engaged in that line of work. While more than 40 percent reported using a smartphone to search for information related to their future career, the availability of a role model in their community appears to play a strong role in determining if youth are able to make choices related to their career.

Both boys and girls also indicated how social responsibilities would ultimately shape their decisions. A class 10 girl from Sitapur said to the survey team, “My father says he will let me complete my BA before I am to be married, although my brother says that they can arrange my married once I get admitted. I can’t say anything in such matters; it is up to them.” This experience was similar for many girls, who indicated that marriage will play a strong role in determining their future, while boys felt they were expected to earn enough to pay for all household expenses. These reasons also lead to a lack of aspirations around vocational work and agriculture, as they are not seen as socially acceptable or lucrative futures.

The influence of socio-economic contexts on career choices is undeniable. This underscores the need to establish a system that recognises the role that social milestones play in determining the career choices of young people. At the same time, the education system should provide pathways that enable youth to overcome the barriers imposed by these conventions.

What next?

Rather than inspiring lifelong learning, it appears that the consequence of the current model is burnout before adulthood. When the education system acts as sieve, and we see masses of youth who are unskilled and unemployable, we must ask ourselves: Why are we still trying to filter our adolescents based on their ability to clear exams that might not be relevant for the current job market? There are some clear learnings from ASER 2023 that educators need to apply:

- As access to smart devices increases, it is probable that digital literacy will automatically grow. This needs to be leveraged to help youth acquire skills that are going to be relevant for the future of work.

- Increased access to smartphones offers us the opportunity to develop open learning models that includes focus on twenty-first century skills like creativity without worrying about the restrictions typically faced by the school system.

- Young people need accessible role models in order to be able to break social conventions and make meaningful decisions to pursue their dreams.

We need to shift towards a model that incentivises learners to learn more, well after they leave the confines of a formal system.

—