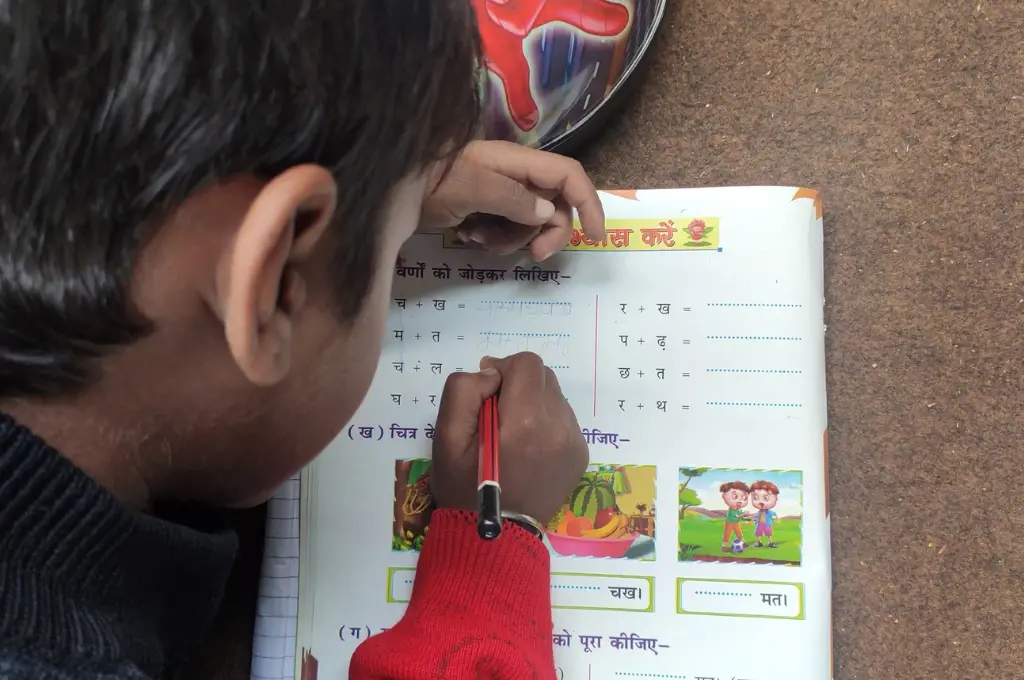

According to the UDISE+ 2021–22 report, which collects data on school enrolment rates, approximately 54 percent of students in India are enrolled in government schools. On the other hand, private schools saw a decline of more than 7 percent in their enrolment rate during 2021–22. This was a reversal of the trend between 2015 and 2020, when private schools saw an exponential growth in their enrolment. Overall, however, the number of school dropouts has steadily decreased over the years.

But are these numbers sufficient indicators of the performance of government and private schools? How are they perceived by parents and society at large? And finally, what do they tell us about India’s education system?

On our podcast On the Contrary by IDR, we spoke with Aditya Natraj and Parth Shah to find the answers to these questions, and to understand the different roles played by government and private schools.

Aditya is the CEO of Piramal Foundation. Before taking on this role, he founded and led Kaivalya Education Foundation, which works entirely with the government school system. Parth Shah is the founder-president of the Centre for Civil Society, an independent public policy think tank. His research and advocacy work focus on the themes of economic freedom, choice and competition in education, and good governance.

Below is an edited transcript that provides an overview of the guests’ perspectives on the show.

Government and private schools shape ideas of democracy and social justice

Aditya: Schooling is not just a utilitarian goal for the sake of the child. I’d like to zoom out and look at schooling as a larger democracy-building project. We are a very young democracy. Just 76 years ago, we were 550 princely states. We did not have the concept of India. Public education is one of the key tools for building that concept. [Our school diaries] used to have ‘unity in diversity’, which is reinforced [as a value], because I needed to believe and affiliate. I’m from Tamil Nadu; I need to affiliate with a person from Tripura, Jammu and Kashmir, and Jaisalmer, etc., whose food and culture are substantially different from mine. Public education helps in the process of creating that democracy, saying, “What are the common values by which we live? Why have we come together?”

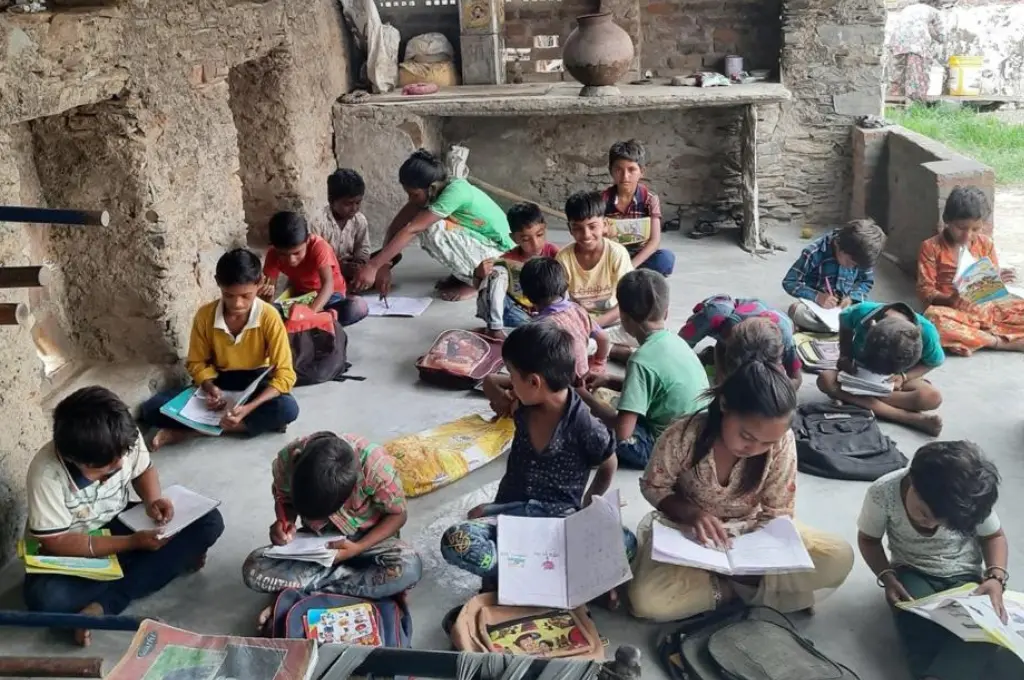

Then there is the social justice perspective. We are a country that has huge diversity in terms of caste. There are not just Dalits and Bahujans, but also particularly vulnerable tribal groups. So for social justice reasons as well, making sure public education is accessible to everyone is extremely critical. We really need to build democracy, social justice, and the idea of India. And the public education system is very critical at this stage in the country’s growth and development.

Parth: My choice for emphasising the role for private schools is largely based on…experience of the fact that monopolies are bad. There are certain public goods such as education, healthcare, and social support—what we normally call welfare—in that category, where you don’t really want to have a government monopoly. We have had an aided school system in India from the very beginning, and even the government recognised that you need to promote different kinds of schools, different approaches to education, and different pedagogies. And, therefore, the aided school system was one way for the government to support the private sector and provide that alternative option. Actually, Kerala, which has been seen as a shining example of the education system in India, has [one of] the highest proportions of privately managed schools compared to any other state in India.

The second [reason why I think private schools are important] is parental choice. I do believe that parents should have the right to choose what kind of education their children get. And this right should not be controlled by the state by providing just one kind of schooling system in the country. The UN Charter of Human Rights has three clauses regarding the right to education. The first two are about it being free and compulsory. The third clause, which unfortunately is hardly ever talked about, states that the parents have a prior right to decide what kind of education should be given to their children.

I think the third [is] about the Indian [school] system. When we talk about ‘affordable’ or ‘budget’ private schools—my take is that those are largely community schools. These are not the schools that somebody from outside the community started. Usually, people living in the same slum, same neighbourhood thought that there was a demand for education that was somehow not being met, and this was an opportunity for them to provide education. These three reasons tell me very clearly that we need to emphasise multiple systems of education delivery.

[When it comes to] the idea of India and social justice, people normally assume that that can happen only in government schools. Even private schools are equally, if not more, capable of promoting that kind of inclusiveness, solidarity, and social justice.

The two school systems adopt different approaches to equity and inclusion

Parth: The way I think about the kind of education system we want is primarily based on the simple fact that each child is unique, and if you provide customised, personalised input to the child, then you will get a more equitable outcome at the end. The approach that we unfortunately have taken in India—which the Right to Education Act is a prime example of—is to standardise inputs. If each child is unique and you provide standardised input, you get very unequal outcomes. The thinking has been that “How can I provide equitable education to all children across a country as diverse as India?” “How could I have a school in Balangir which is as good as one in Bangalore?” Therefore, the focus in achieving that equity is largely on building the same core type of schools. But if you really believe that each child is unique, then you need to provide differential input that is suitable [for] and personalised to that child.

Private school systems do more of this. There is a lot more pressure on the system to deliver on this front and respond to parental demand, which may or may not be the right thing all the time. We know that the parents can also be misguided about what they want from the schools. But generally, over a period of time, my sense is that if you want to build a system for the long term, then you need to allow parents to play that role. Maybe the role for samaaj and sarkar is to educate parents about what makes for good education and what’s good for the children.

Aditya: I don’t disagree that equity is the final goal. The question is, how do you achieve social equity? I agree that low-budget private schools, which are just set up as mom-and-pop shops, are okay. But as soon as you go one level above that, the reality is that those private schools are less likely to admit a child with special needs or learning disabilities. I went to a high-performing government school in Delhi and interviewed the principal. I asked him, “How are you performing so well?” His school was performing better than private schools, and this is approximately 12–15 years ago. He said, “We do the same thing that private schools do. In grade 8, we wean out 10–15 percent of the children. In grade 9, we wean out another 10–15 percent of the children and tell their parents to put them in some other school. So then, by grade 10, we have 100 percent pass rather than 70 percent pass. If private schools are allowed to do this, why can’t I do it?”

So if the rules of the game are that [as a government school administrator,] I have to take the weakest, the poorest, and the first-generation learner, and you (private schools) can select and take the best, you’re then competing with IIT when you are an inclusive engineering college. And these are two different models. So I think government schools are really good at inclusion. Because as a mandate, we have no choice. I come from the corporate sector. I’m all for private incentives for this delivery, but I’m not able to see how to create the incentives in [a manner] that inclusion is also served. And I think that’s what government schools are really good at.

Perception plays a huge role in informing parental decisions

Parth: In terms of why parents prefer private schools, there are many reasons. Often, one of the primary reasons people cite is the English medium. Parents see that as a ticket to a better future for their children. My views began to change sometime in the mid 2000s when we began to do a voucher pilot in Delhi. It was a three-year pilot program, so I was interacting with the same group of parents over the same period. I realised that what I assumed as the reason for their preference is really last on their list. The things they actually talk about are things that we trivialise. For example, schools that close their gates if students are more than 10 minutes late, ensure homework is given and checked, and have teachers who write comments in the students’ homework notebooks are things that influence parents. These small but significant factors, such as daily teacher engagement and visible feedback, greatly influence parents in choosing those schools. And you can now contrast each one of them in terms of the general perception of government schools. You can understand why parents are willing to sacrifice. If parents are earning INR 20,000, one-third of that monthly income is spent on education. This is everything, not just school fees, [but also] the tuition classes and all of those things that parents do. And so it’s not an easy choice for parents to send even one child out of three or four to a private school. It’s a huge sacrifice.

Aditya: There’s a significant perception problem between government versus private. ASER data has shown that, after adjusting for socio-economic differences, both sectors perform equally in terms of educational outcomes. Unfortunately, that’s not the perception in the market. If you are from the second quartile in the country and going to a private school, and I’m from the fourth quartile and going to a public school, the perception might be that you’re better off. However, the reality could be that your parents are actively supplementing your education in various ways. This highlights a significant perception gap between the two types of schooling.

In addition, any district in the country runs approximately 2000 schools. Two thousand schools, half a million children—you will be serving midday meals half a million times. Even at a Six Sigma level, there will be a possibility that one of those meals is infected in one of six days of the week. But that will be blown out of proportion by the media, [which will go on to say,] “The government does not work.” On the other hand, private schools give ads in the local media, saying, “My child got 98 percent, 97.6 percent, and 97.2 percent.” And governments don’t give ads in the paper. So systematically there is a belief that the government does not work and that private works. On the other hand, IIT and IIM work; they are completely government-run. If you set up a private institution, it’s going to take you several years to catch up with IIM’s reputation or IIT’s reputation.

So, something has happened because of which perceptions in the school sector are such that we believe that government schools don’t work. Let me give an example. A teacher whom I worked with…the principal of a school…works with this child from grade 1 to 3, who starts performing [well]. As soon as this happens, the girl’s parents say, “Hamein nahin laga ki yeh ladki padh sakti hai. (We didn’t think this girl would be able to study.) She seems quite smart, let’s put her in the private school.” Two years later, the child was not performing [well] enough because she’s not used to this heavily disciplined environment. She needs love, care, a sense of joy. The parents had to bring her back to this [government] school. I’m giving this example to say that different children need different types of things.

Education is not a customer-focused business alone.

The reality is that there are a bunch of schools that are extremely regimented, and the discipline they require is detrimental to children’s growth. So, the more homework you give, the more you scold my child, the more you’re perceived as a better school. These are perceptions unfortunately, and I have to stall governments from giving in to consumer needs. Education is not a customer-focused business alone. If your child asked for something, you don’t serve it immediately. Because education is the process by which you help the child self-regulate. If school systems become too consumer-centric [and start] saying, “I will listen to the parent and the parent will listen to the child,” you will create a society that is quite dysfunctional as opposed to [one that is] able to regulate itself. Therefore, I think we should be careful about listening to parental choice.

Parth: I am equally proud of the fact that we have great IITs and IIMs, even though they are run by the government. I hope the government is able to do with school education what it has done in higher education. So, there is no doubt in my mind that we are both in favour of both systems, as long as they do well by the children. That’s ultimately what our concern is.

Now, with regard to perception and reality, you have to ask what is being measured by the ASER survey, or for that matter, any other research that looks at learning outcomes. This is what they are trying to quantify to judge which [kind of] school performs better. What they measure is purely the academic part, which is what can be measured. And, on that basis, they are looking at the difference between the two kinds of schools. What I talked about earlier, what parents really want, and why they choose private schools. Academics is actually not as important. And most parents are actually unable to even judge the quality of the academic performance of the school. But they’re able to judge whether the schoolteacher is engaged every day or not. So, all the other things that matter to parents are not even measured in any of this research, which is my beef with many researchers. You are measuring what’s easy to measure: the three Rs [reading, writing and arithmetic]. It’s important to understand that the difference in perception and reality is based on our assumption of what is measurable, which is different from how parents are making choices.

The education sector has made significant progress, but more needs to be done

Aditya: If I just look at when I joined the [education] sector 20 years ago… In 2002, there was a probe report, which said there were 87 million children out of school in India—that’s more than the population of Germany. Today, that number is at 13 million—which is still substantial. However, it is a significant achievement considering the much larger population base now, as compared to 2002, when the problem was even more acute with a smaller overall population.

So one, I think at a societal level, the perceptions about education being our ticket out of poverty are very embedded. Parents know the only way out is education and more education.

The key is that we also push for decentralisation.

The second reason for positivity is the fact that [until] 20 years ago, education was a directive principle of state policy. There was no right to education, there was no educational cess, there was no national curriculum framework, there was no National Education Policy (NEP) the way there is today. All these are building blocks, which you might not see the gains of immediately. But to create the Right to Education was a movement for 15 years before it finally became a right. All of us pay for an educational cess, apart from the taxes that we pay. So, I think the financing, the policy, and the infrastructure availability are all getting much better than we could ever have imagined.

The key is that we also push for decentralisation. I don’t know why states need to decide things. An individual district in India handles 800–2,500 schools. That’s a huge number. So how do you decentralise to districts? If you go further down from a district, at a block level, there are 100–250 schools. The power distribution between teacher, school, cluster, block, district, and state needs to be rebalanced, much more towards the teacher. And that is a journey for the next 30 years.

Parth: As you know, the work that we do either in policy or on the ground, cannot be sustained year after year unless you’re optimistic.

I have to say that my experience with the pandemic has really made me question what I thought was improving. So I see a very anti-private sector, anti-parental choice mindset within the government, which has obviously existed in the bureaucracy for a long time. But also, in the larger society, [this mindset has] become obvious in terms of what happened in the last few years and the support that private schools did not get. And here we are talking about high-fee private schools, we’re talking about no fee or very low-fee private schools. And so that has really made me a little less optimistic in terms of how the future looks. Now, yes, the NEP has made some right noises, and you can say that’s a really optimistic sign. It remains to be seen how far they will actually come through when the rubber meets the road, when this actually gets implemented. And so, I’m a little less sanguine now in terms of what is going to emerge as a result of what we have experienced.

You can listen to the full episode here.

—