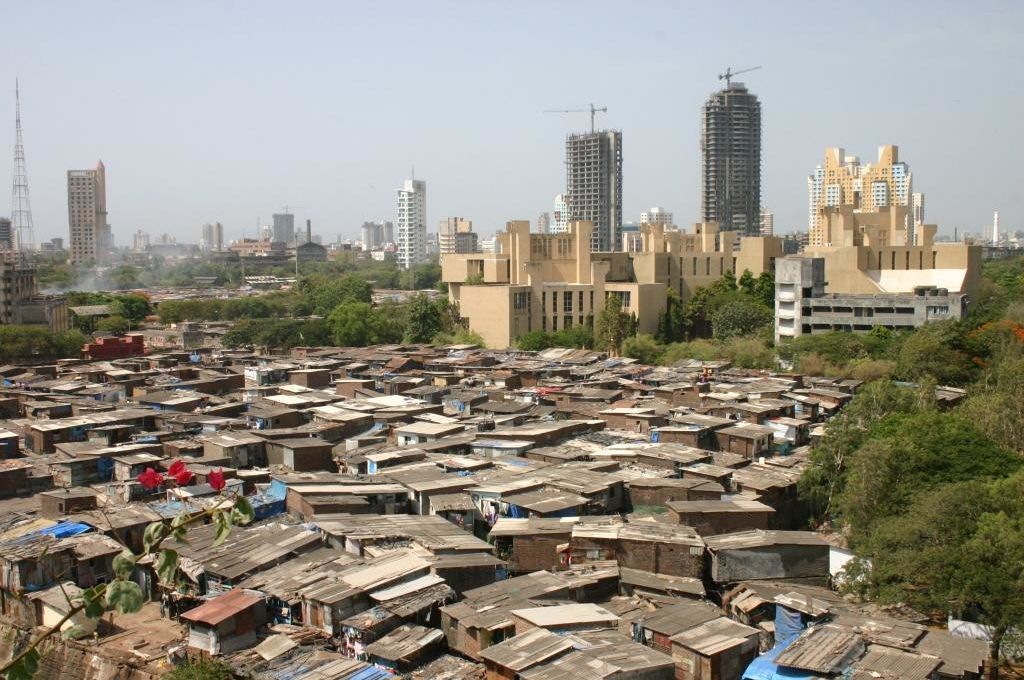

In 2020, with millions of migrants stranded in cities, in despair, India faced a social and humanitarian crisis it was not prepared for. Today, with the second phase of COVID-19, there is fear, denial, fatigue, and mistrust in the system and political apparatus, rampant misinformation, and vaccine scepticism in Shivaji Nagar, one of the poorest and most underdeveloped neighbourhoods in Mumbai.

Located in the city’s M East ward, Shivaji Nagar with six lakh residents, is 11.5 percent of Mumbai’s informal settlement population. Many of them are migrants from across the country. Last year after the lockdown was announced in March 2020, residents faced a range of challenges, as highlighted in a study carried out by the nonprofit organisation, Apnalaya. Incomes were impacted, and ability to pay rent was a chief concern. Many respondents to the survey reported being “on the brink of starvation” during the lockdown. Eighty-one percent of people struggled for food and 70 percent had to borrow money to buy rations and water. A majority of people (72 percent) were more concerned about unemployment and loss of wages, than they were about their own health or that of their families.

Given the income and food insecurity, relief efforts back then were largely focused on ensuring that disadvantaged communities had access to food, rations, and safety equipment to quell the spread of COVID-19. Now, with the precipitous surge in infections, the system’s focus has shifted to medical solutions. However, the poor are still facing the same issues they were last year, with little to no support from the government.

Making a bad situation worse

Chief among the problems faced by Shivaji Nagar’s residents are the many administrative and bureaucratic hurdles that inhibit access to the various relief measures announced by the government. One example of this is what ‘counts’ as a COVID-19 death, and which bereaved families are therefore entitled to support from the government. “If it [the death] happens post 14-15 days and after a negative RTPCR test result, we have been told that there are instances of the death certificate not citing COVID-19 as one of the causes,” says Poornima Nair, from Apnalaya. This not only deflates the overall statistics, but can also impact the relief that a bereaved family might be entitled to from the state.

Borrowing to cover expenses, has also begun. Migrant workers who returned to Mumbai after the lockdown, did so because they needed the income. Many of them have lost their jobs yet again, and are unable to return home. Those that had managed to survive in 2020 on their savings, have exhausted them entirely. So, they are beginning to borrow—potentially digging themselves into a deeper financial hole.

Fear, and rejection of the second wave of COVID-19

With the desperation they experienced in 2020, people’s trust in the system has evaporated. The current perception among many from poor families is that ‘yeh badein logo ki bimari hain’ (this is a rich person’s disease), because most of the cases in the second wave have been from high rise buildings, among middle class and upper-middle class households. This is in contrast to 2020, when there were more cases among people living in slums.

People in Shivaji Nagar are no longer experiencing the crisis around them in the same way as they did last year, and they are losing their livelihoods, homes, education opportunities for their children. At the same time, they are also facing stigma from the middle class and the wealthy, because of which they are sceptical that the situation is in fact, as bad as is being portrayed.

Increasingly, there seems to be a belief that this second wave is a political stunt, for people in power to make more money at the expense of others.

Moreover, they are afraid. Piyasree Mukherjee works with the nonprofit, Swasti, which has been offering COVID-19 relief in Shivaji Nagar. According to Piyasree, there is still a lot of stigma. “People don’t want to disclose that they might be COVID-19-positive, like HIV and tuberculosis. Because last year, people were taken away to isolation centres, so many got scared. The denial comes from the fear that I will anyway not get any support.”

Increasingly, there seems to be a belief that this second wave is a political stunt, for people in power to make more money at the expense of others. That has led to a great deal of scepticism with anything relating to the virus. None of this meanwhile is being addressed by the media, or the government.

Vaccine scepticism and misinformation

The lack of trust has made it extremely hard to convince people to get the vaccine. It has already created space for misinformation to spread like wildfire. For instance, a WhatsApp message about a negative reaction to a vaccine from someone in Thane reaches people in Shivaji Nagar in no time. In a vacuum of trust, people are likely to believe what they want to. Some believe talk of this COVID-19 surge is politically motivated; and, with a soaring black market for medical supplies, people also question whether this is all a ruse for store owners and the medical fraternity to make money.

There is also a large gap between the information people on the ground are looking for, and what mainstream media and the government are focused on. Current media coverage focuses largely on macro issues, and what is happening at hospitals. There is little coverage of what is happening at a local level. This helps fuel WhatsApp rumours. When it comes to the vaccine, the government provides information on how to register on the CoWin platform and get the vaccine; but there is little to no information that dispels rumours about the vaccine itself, or allays people’s fears about dying from the vaccine. It is not enough to repeatedly tell people to wear masks. If we want to behaviour to change, we need to respond to people’s concerns first. With an almost laser-like focus on the medical aspects of the crisis—with the exclusion of almost everything else—the system has yet again failed its most vulnerable people, who are still facing a humanitarian disaster, without any income or food security. No wonder there is a complete lack of trust in the system.

—

Know more

- Read more about how Bihar has been responding to the COVID-19 second wave.

- Read about the unique challenges of and suggestions to respond to COVID-19 in rural India.

Do more

- Support nonprofits working towards towards COVID-19 relief efforts in Mumbai, Maharashtra—Apnalaya, Apni Shala Foundation, Arpan, Dignity Foundation, Dr Ambedkar Sheti Vikas Va Sansodhan Sanstha, Human Welfare Charitable Trust, Myna Mahila Foundation, Railway Children India, Rise India Foundation, Samruddhi-A WTA Foundation, SNEHA, Training and Educational Centre For Hearing Impaired (TEACH), Udhhar Multipurpose Society, and United Way Mumbai.