‘Poromboke Unnaku Illa, Poromboke Ennaku Illa. Poromboke Ooruku, Poromboke Boomiku

Poromboke Un Porupu, Poromboke En Porupu, Poromboke Oor Porupu, Iyarkaiki Boomiku.’

[Poromboke is not for you, nor for me. It is for the community, it is for the earth. Poromboke is in your care, it is in mine. It is our common responsibility towards nature, towards the earth.]

These words come from ‘Chennai Poromboke Paadal’, a song written by singer-songwriter Kaber Vasuki and featuring Carnatic vocalist T M Krishna. The song was part of a campaign to reclaim the word and restore its worth.

Poromboke is an old Tamil word for shared community resources such as water bodies and grazing lands that benefit the community and remain outside private ownership.

In colonial times, poromboke referred to land exempt from assessment, either because it was set aside for communal purposes or because it was considered uncultivable. Over time, as this land did not fit neatly into frameworks of privatised property, the word itself evolved into an insult—used to imply that a place or person holds no value.

This shift mirrors how common lands are often dismissed as wastelands, leaving them vulnerable to encroachment. This disregard extends to other commons such as wetlands, water bodies, and forests, which face increasing diversion for private, economically profitable uses. Such changes push them out of public imagination and weaken our understanding of how deeply they are woven into daily life.

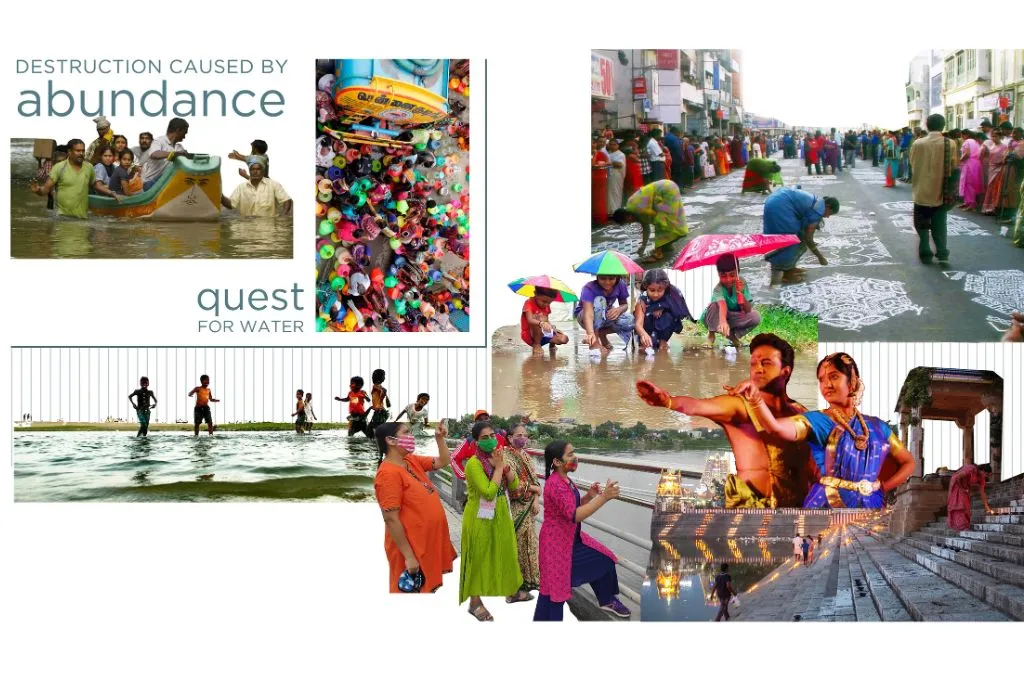

In rapidly urbanising Indian cities, this fractured relationship is even more visible, especially between communities and the water bodies that once sustained them. Much of this stems from an approach to water that focuses only on controlling and pushing it away, rather than understanding how it naturally moves through a city. Urban water management has long prioritised grey infrastructure designed to keep water out of sight. Wetlands, tanks, and canals have been encroached upon or built over, in part because water is treated as a liability—something to drain, exclude, or seal off.

However, the consequences are catching up. Cities swing between extreme flooding and severe water shortages. As these patterns repeat across urban India, a few questions become impossible to ignore: What would it mean to see water not as a threat, but as the foundation of urban life? What might our cities look like if water was made visible, accessible, and ecologically integrated? And what possibilities emerge when we treat urban water bodies as commons once again?

These questions gain sharper focus in Chennai, a city shaped, sustained, and repeatedly tested by water.

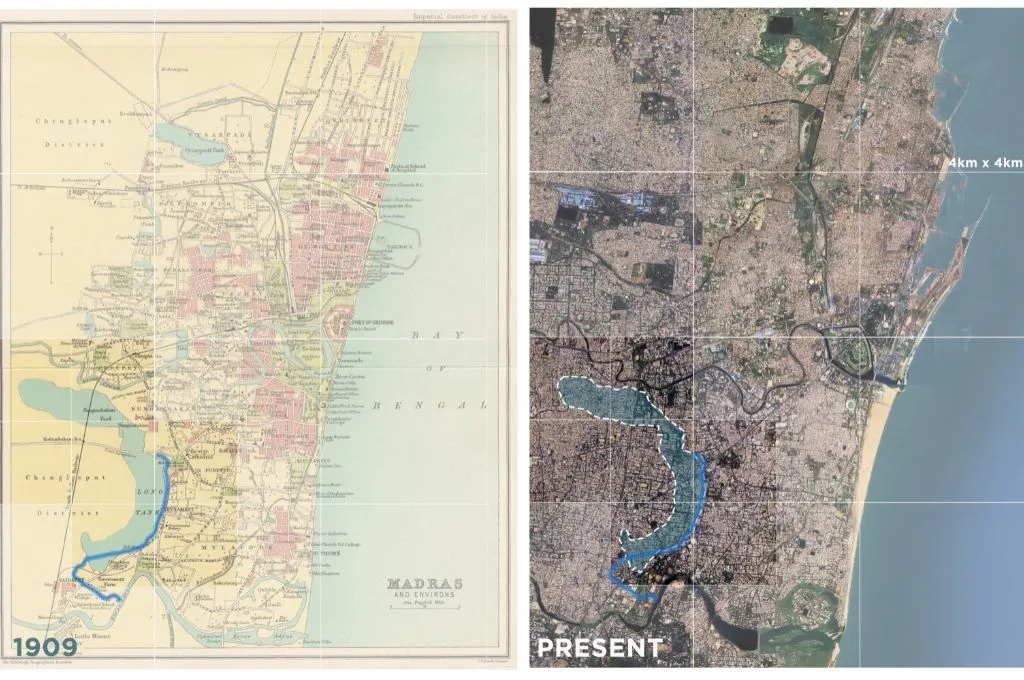

Chennai’s waterscape

In Chennai, water acts as both memory and force, continually reclaiming its space. The city’s traditional eris system was used for water management. It was a vast network of interconnected tanks and ponds used that captured rainwater, recharged groundwater, reduced soil erosion, and buffered the city against floods. These tanks expanded during the monsoon and contracted in dry months, adapting naturally to the rhythms of a rain-fed landscape.

Over time, however, Chennai’s seasonal water rhythm suffered disruption. Colonial planners insisted that rivers must always flow, canals remain navigable, and tanks stay full, regardless of droughts, floods, or tidal shifts—an expectation at odds with the ebb and flow of the monsoon cycle. This approach, which clashed with the region’s climate, led to the gradual erasure of spaces designed to temporarily hold water. Since tanks appeared as unused land when dry, they were slowly filled and built over. Today, with no place for rain to collect, even moderate showers spill onto streets.

Take the Long Tank for instance. Once a 70-acre lake west of Mount Road, connected to the Nungambakkam Lake Area in Chennai, it was filled with concrete and built over by the 1970s, dismissed as unused whenever it ran dry. Once filled, the newly created land was seen as more profitable and, in this case, it was handed over for a new college campus. Today, only the Mambalam Canal survives as a small remnant. The canal and nearby areas now flood quickly because the lake that once held excess rainwater no longer exists. This forms part of a larger pattern in Chennai, where many seasonal lakes have been continually filled with concrete, worsening the city’s flooding problems.

The lesson here is clear: When we keep water at bay, we detach ourselves from its presence until it overwhelms us. But when accepted as an essential system shaping urban life, water opens up new possibilities for design. The shift from controlling water to directing and celebrating it can generate frameworks that embed water in the urban realm and make it visible again.

Re-commoning water spaces

One way to achieve this is by enabling communities to regain their access to these spaces. When a lake, canal, or wetland serves as a shared commons, neighbours contribute local knowledge, monitor and maintain the place continuously, and enforce norms that discourage dumping and encroachment. As communities build stewardship over canals, tanks, and wetlands, these spaces can once again perform their ecological role in absorbing and holding monsoon waters.

In Chennai, where intense rains often coincide with blocked drains and encroached waterways, reclaiming these spaces as shared civic infrastructure can make neglected water systems function as public commons once more. This can take many forms:

- Wetlands that double as parks to provide recreational space while naturally slowing and filtering stormwater during intense rains.

- Restored temple tanks with stepped layout that hold monsoon run-off and recharge groundwater, while also connecting communities to traditional water spaces.

- Shaded canal promenades that improve access, reduce heat, and allow water to spread and slow down to avoid overwhelming drains.

This Living with Water approach, exemplified in the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan, illustrates how water can integrate into everyday urban life, transforming it from threat to an asset. Through water plazas, green streets, and restored canals, the plan demonstrates how common urban spaces can double as flood buffers. This also offers us a way to return water bodies to public imagination as commons rooted in care, culture, and community.

In Chennai, where the idea of poromboke already reminds us of shared, communal relationships with land and water, this shift becomes especially relevant. Building on this, I propose the idea of ‘poromboke urbanism’ as part of my research, which focuses on treating water bodies as urban commons—cultural, ecological, and educational assets—and designing with the rhythm of water instead of against it. Using a speculative urban design approach, I reimagine the lost Long Tank in Chennai to showcase how reconnecting communities to water through design can create resilient, place-based responses to flooding and the decline of urban public space.

These relationships with water—how people move through it, learn from it, and celebrate it—became the basis of the design explorations:

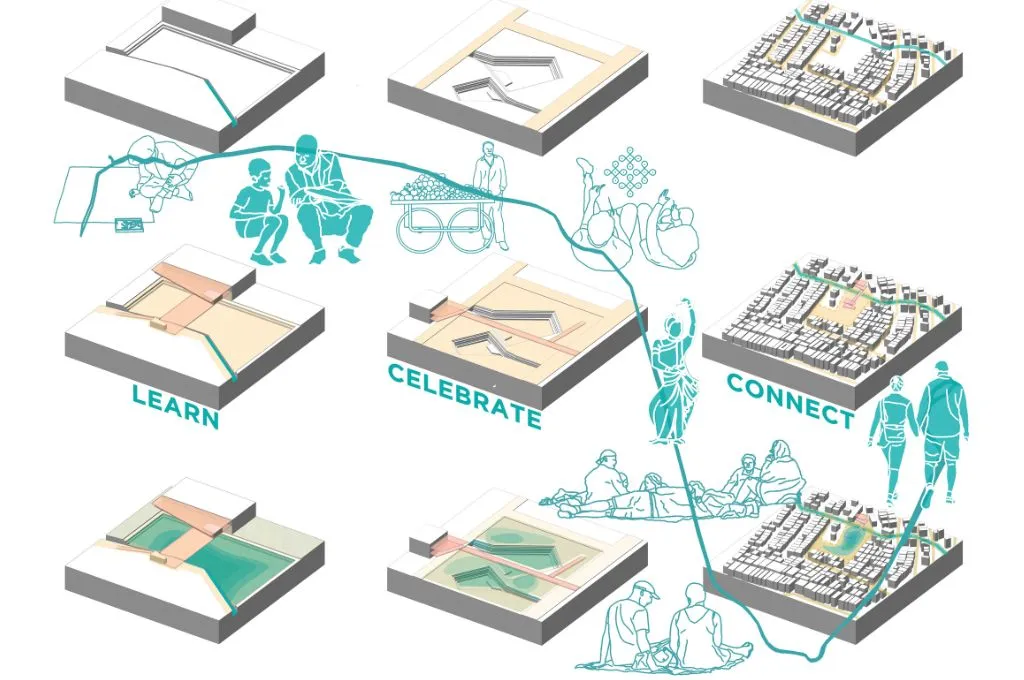

1. Connect: Water as public infrastructure and movement

The first relationship is to reconnect people with water by making it visible, accessible, and integral to public life. In Chennai, the Mambalam Canal stretches for approximately 5.7 kilometres, running from the neighbourhood of West Mambalam and draining portions of several localities before meeting the Adyar River. Surrounded by dense development, commercial hubs, and a mix of multi-storey and low-income housing, the canal today faces severe pollution and encroachment. Waste is regularly dumped into it, its carrying capacity has been reduced, and its flow is disrupted.

Periodic desilting and restoration by city authorities have done little to shift public perception.

Additionally, with no walkway, no public amenities, and no continuous path along its length, the canal remains isolated from the city’s public realm. Cut off from everyday life, it evokes no sense of ownership among surrounding communities and remains invisible to the rest of Chennai.

To reconnect the canal to its people, the idea is to make it accessible and safe at the same time, by creating public pathways that let people walk along and over the water, while also protecting nearby neighbourhoods from flooding.

This approach draws inspiration from Hidden Hydrology, which explores lost rivers and disappeared streams through art, landscape architecture, and urban ecology. Similar principles have guided the transformation of the San Antonio River Walk, which turned a flood-prone river into an adaptive, thriving public space.

Following this approach, the first step is to design a water strategy that accepts seasonal flooding, while protecting adjacent neighbourhoods, instead of trying to prevent it. The goal is to guide floodwater safely while making it useful for the city and its people.

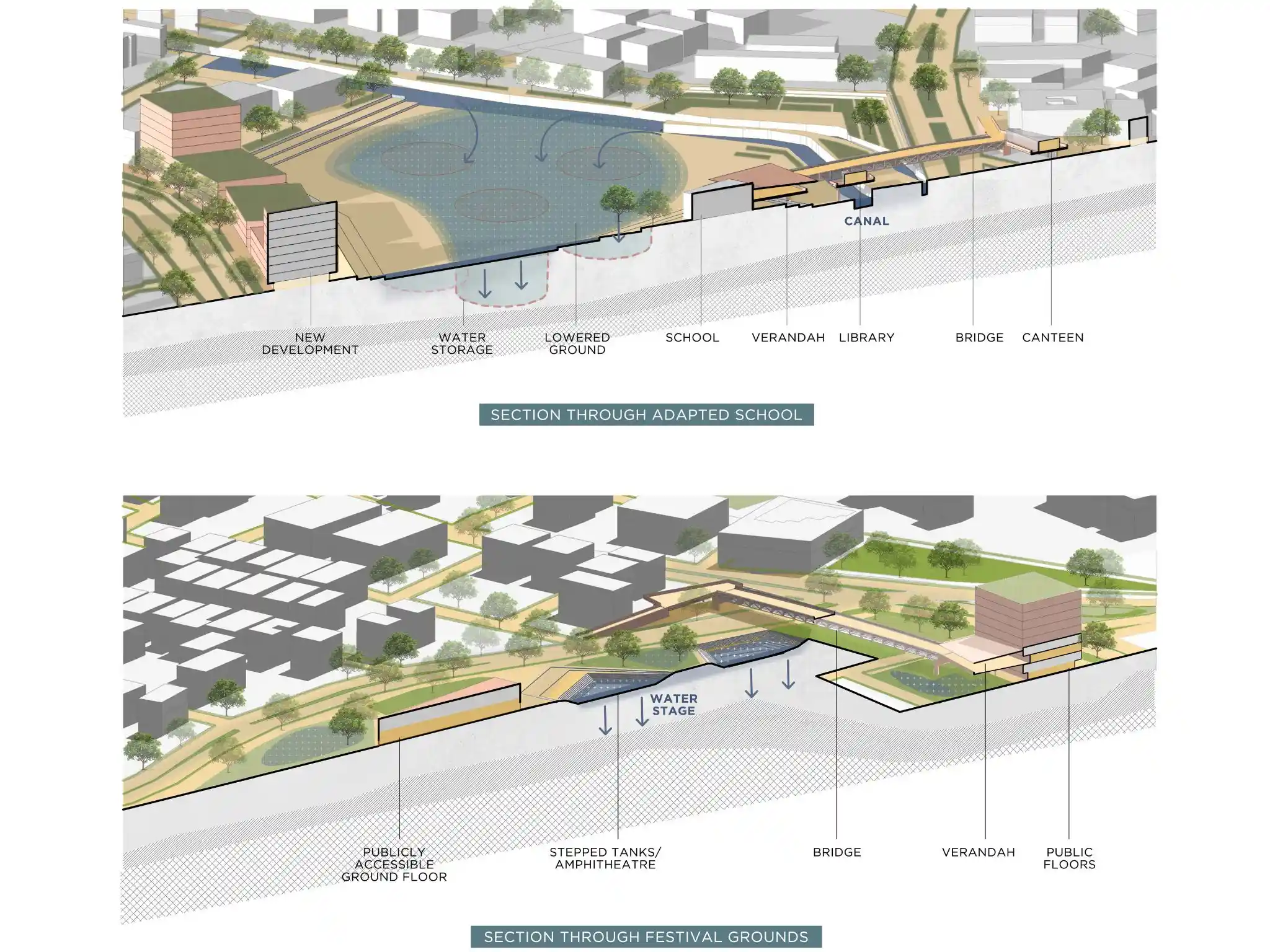

The process shown in the graphic below explains how holding water in lower landscaped areas allows it to be absorbed into the ground while storing the excess water underground. Bridges and raised pathways follow the natural flow of the canal, reconnecting people safely to the water. Widening the floodplain gives water the space to spread, slowing it down, reducing run-off, and protecting nearby neighbourhoods. Raised pedestrian routes, bridges, and landscaped edges can further guide water into retention zones.

These elements reconnect the urban fabric to the canal, transforming a cut-off water body into a traversable and visible public space.

2. Learn: Water as living curriculum

The second relationship focuses on learning about the hydrological landscape. A precedent for this approach can be seen in the West Philadelphia Landscape Project, which developed a curriculum organised around the Mill Creek Watershed, where the entire neighbourhood became the classroom and the school its centre. Through this place-based method, students learned how to read their landscape, trace their past, understand their present, and imagine their future. Such engagement fosters long-term stewardship, where learning from and around water translates into caring for it.

Within this vision of poromboke urbanism, schools built on the land of the Long Tank can be re-envisioned as living classrooms for hydrology. The design integrates water management with learning: Playgrounds can be shaped to create sunken spaces so that rainwater naturally collects and seeps into the ground, reducing the chances of flooding. Extra water can then be stored underground and reused during dry months. The schools are also opened up to create a new kind of public space (shown in yellow in the graphic below).

By making hydrological knowledge visible and civic, these sites transform poromboke from ‘waste’ into an active commons of expertise and stewardship.

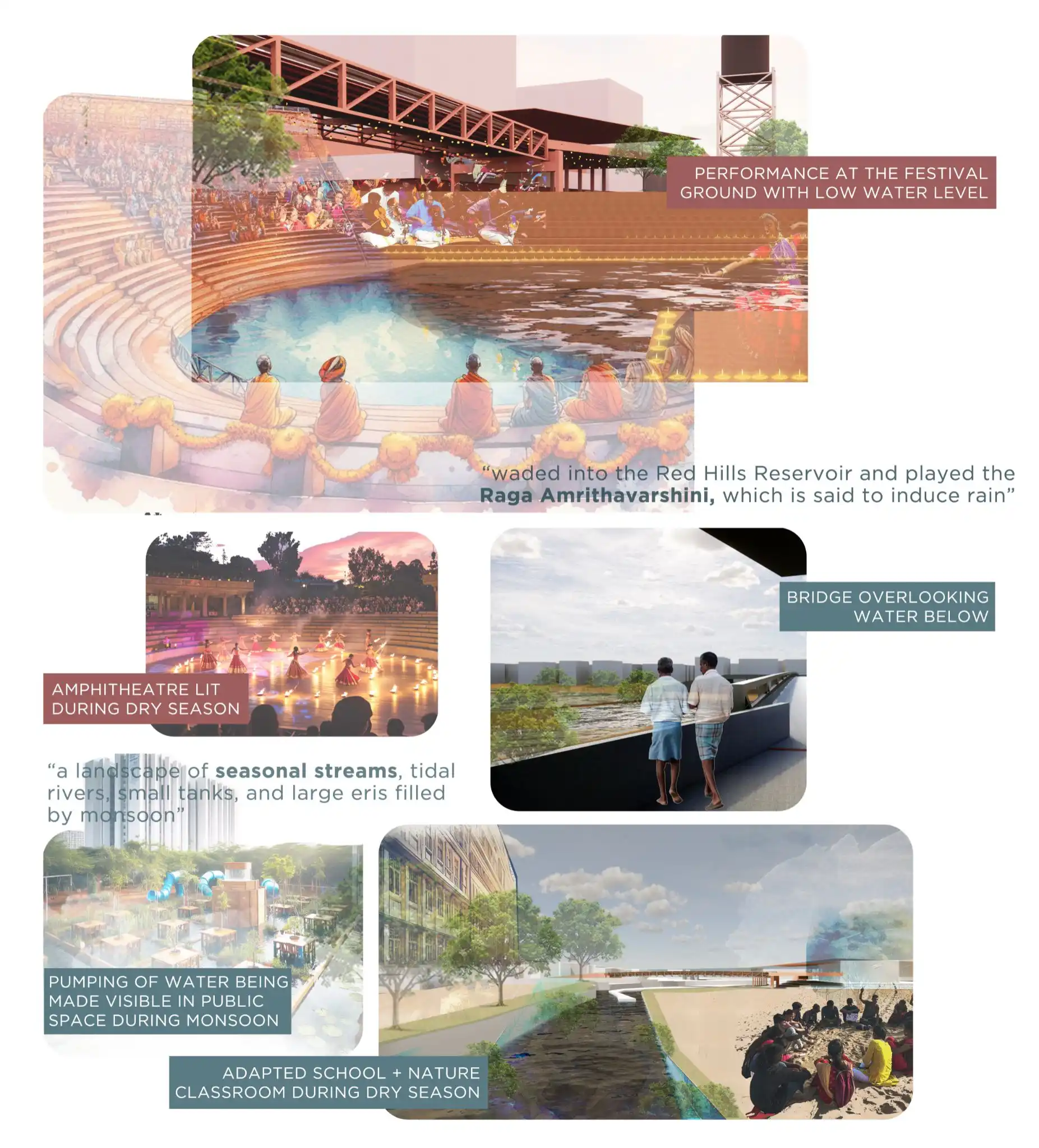

3. Celebrate: Water and culture in public life

The third relationship centres on celebration. In Chennai, water has long held a sacred connotation through temple tanks and rituals that mark its arrival. If the coming of the rains were planned for and celebrated, it could transform the city’s relationship with its harsh monsoon—from a season of crisis to one of renewal. A parallel can be seen in La Quebradora Water Park in Mexico by Taller Capital, where platforms, plazas, and walkways transform urban flood infrastructure into a public and recreational space for the community. Constructed from local volcanic stone and rooted vegetation, these spaces both mitigate flooding as well as generate community life.

While the design language of La Quebradora is rooted in its own geography, in Chennai, similar principles can take form through locally grounded expressions by building on existing practices and rituals. The Margazhi season (mid-December to mid-January), for instance, offers such a rhythm. It is a citywide festival of music and dance that coincides with seasonal rainfall patterns. Poromboke urbanism reimagines an open festival ground tied to this calendar, where performances, canteens, and public rituals occur in sync with the city’s water cycles. This builds on the city’s traditions, where temple tanks and rain-summoning songs sustain a poetic, sensory relationship to water that continues through art, music, and collective memory. Embedding water care in collective life, each Margazhi becomes a public milestone for a more water-sensitive city.

Poromboke urbanism reframes infrastructure as socio-ecological and culturally legible. While this is a speculative design reimagining, it is crucial that this vision is not confined to the academic realm but is actively integrated into the urban fabric of Chennai. For these ideas to take root, fragmented water governance must bring together multiple agencies, citizens, and institutions. In doing so, a poromboke way of thinking about water can begin to take shape—one that works at the scale of the watershed while nurturing neighbourhood-level stewardship through local water champions.

—

Know more

- Learn how scientific interventions and community particpation help in the resotration of Polachery Lake, Chennai.

- Read why residents around Malabam Lake are demanding greater transparency around its resotration.

- Read this article on why cities must reconnect with their rivers.