Across its many communities, India consumes an estimated 6,000 varieties of rice, more than 500 types of millets, and hundreds of vegetables and herbs. But this isn’t all. The richness of the country’s food palate also comes from the diverse and ever-evolving cooking techniques of its people.

Indians were consuming stems, stalks, and peels of vegetables long before mainstream media woke up to ‘zero-waste cooking’. While some of these cooking practices emerged from social norms, others were motivated by local biodiversity and traditional healing practices.

In this conversation with IDR, four chefs from four different tribes in India share their favourite recipes. They explain why it is necessary to preserve indigenous food and ways of cooking, and express their fear of losing the resources and knowledge required to continue these eating habits.

Sodem Kranthikiran Dora, Koya tribe, Andhra Pradesh

I am a home cook and farmer from Chinnajedipudi village in West Godavari district, Andhra Pradesh. I also work as a community outreach person at Humans of Gondwana Project. For the past few years, I have been documenting the traditional food of various tribes in Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Telangana, and other states.

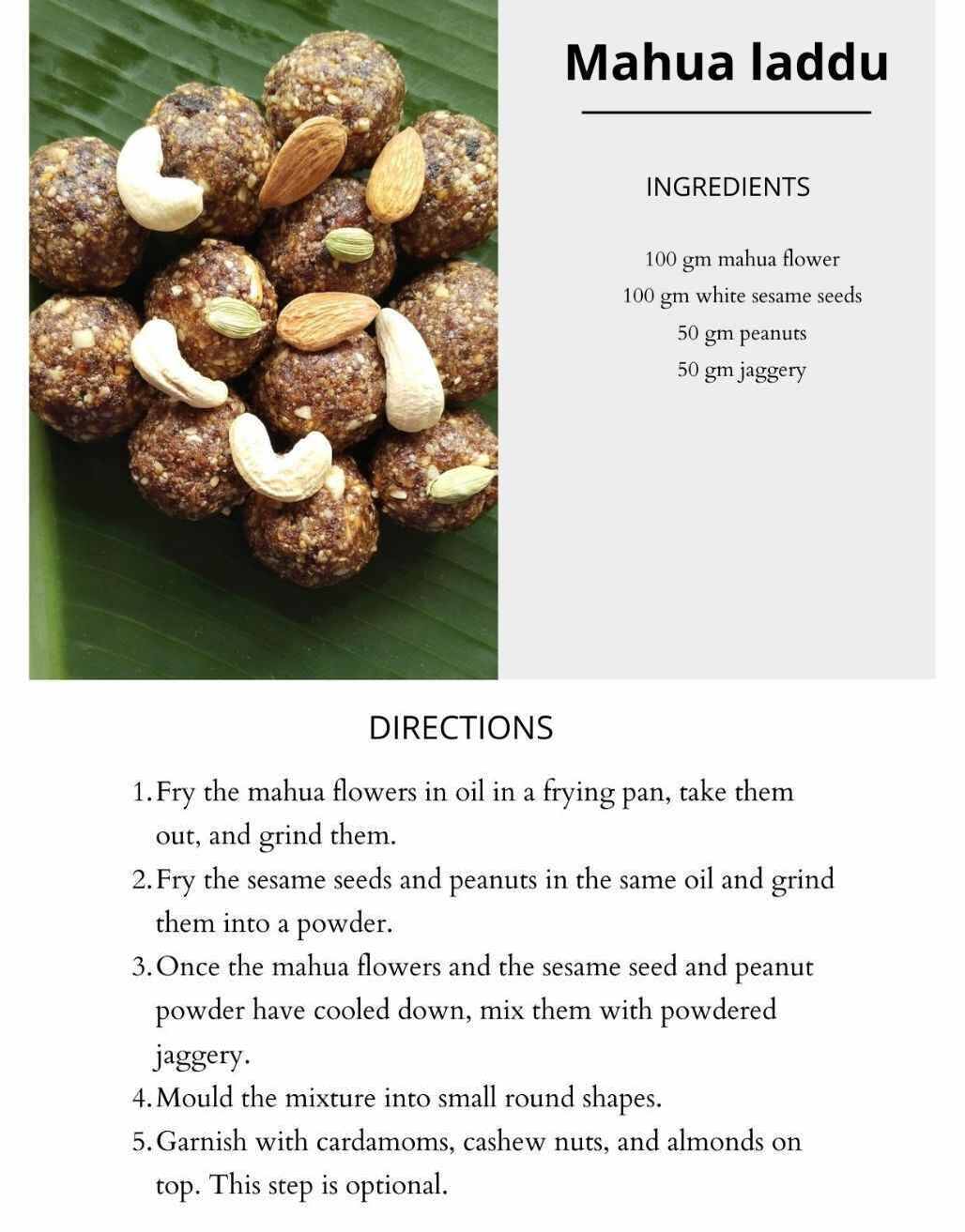

The Koya tribe, which I belong to, has a rich history of consuming nutritious food. Most of our food came from the forests. We ate vegetables, herbs, and flowers, including the mahua flower. Many people have heard about mahua, but they associate it with alcohol. However, the Koyas and other tribes living in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Jharkhand, and Maharashtra use mahua flower to make kheer, jam, biscuits, and laddus. In fact, even now, pregnant women in our community consume mahua laddu because it increases haemoglobin and works as an iron supplement for them.

Mahua and other indigenous food like tembhurni were once abundant in West Godavari district. However, this isn’t the case any more. Now we buy these from the neighbouring East Godavari district. Due to the shifting cultivation that is practised in our district, we lost a lot of forest area where we used to grow mahua trees. Then there are development projects because of which we lost access to the forest. We can no longer legally collect resources from our own forests.

There are small self-help groups that are spreading awareness about the importance of our food and are training people to package and sell mahua products in the market. These groups have had far-reaching impact. In Telangana, the efforts of similar groups caught the attention of an IAS officer who then took mahua to the mini anganwadis, where it is a source of nutrition for young mothers. But such groups need financial help from the government to sustain. It would be great if nonprofits could also focus on supporting these self-help groups in building better market linkages.

Kalpana Balu Atakari, Warli tribe, Maharashtra

In my native Warli community in Maharashtra’s Palghar district, a regular day starts with a breakfast of coconut or rice bhakri (flatbread), followed by meals of toor (pigeon pea) dal cooked with moringa, other nutritious vegetables, and leaves. It might also include suran (yam) curry and boiled shells of the toor pod. Our food habits depend on the season and what grows in our villages during that period. It also depends on what our bodies need in a particular season. For example, in February when the sun is out, we drink ragi ambil (a cooling drink made with finger millets).

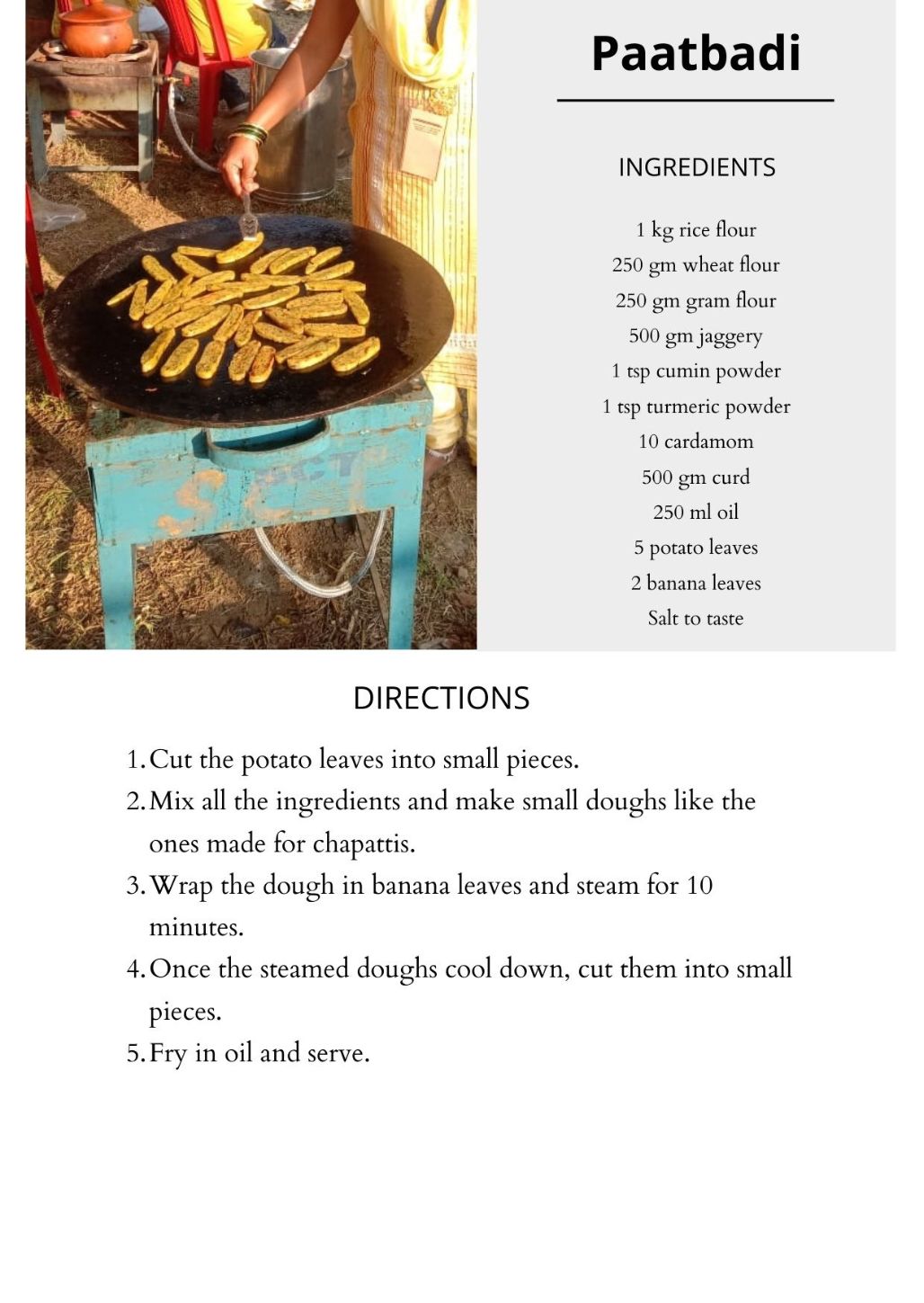

With changing times, our food too has undergone many changes. Our grandmothers cooked food in chulhas (earthen stoves), but we cook on gas stoves and so the food tastes different. Moreover, our younger generation no longer wants to eat traditional food. They want the food that is found in big cities like Mumbai. There is no use telling them that fast food, while enticing, isn’t healthy. So we started innovating with our recipes to make them eat what’s good for them. Since kids don’t like seeing moringa leaves floating in their dal, we dry the leaves and grind them into a powder, which we add to the dal. The kids don’t realise! And our paatbadis (fritters) are a huge hit among them. We make it with potato leaves and banana leaves so that children get the necessary nutrition.

My father used to hunt deer, rabbits, and peacocks, and we would eat their meat. When we lost the jungle, we also lost these animals. We used to eat many parts of the bamboo plant, but bamboo is scarce now. I work with a self-help group where apart from teaching young women how to save money, I also teach them the benefits of Warli food and how to prepare it. These women perform agricultural and other types of labour and then make time for these sessions. They themselves procure the ingredients that we cook with, which means a good part of their day goes in foraging. Loss of time is loss of money for them. I wish the government came up with a way to financially support these women who want to learn and preserve the food of their tribe.

Dwipanita Rabha, Rabha tribe, Meghalaya

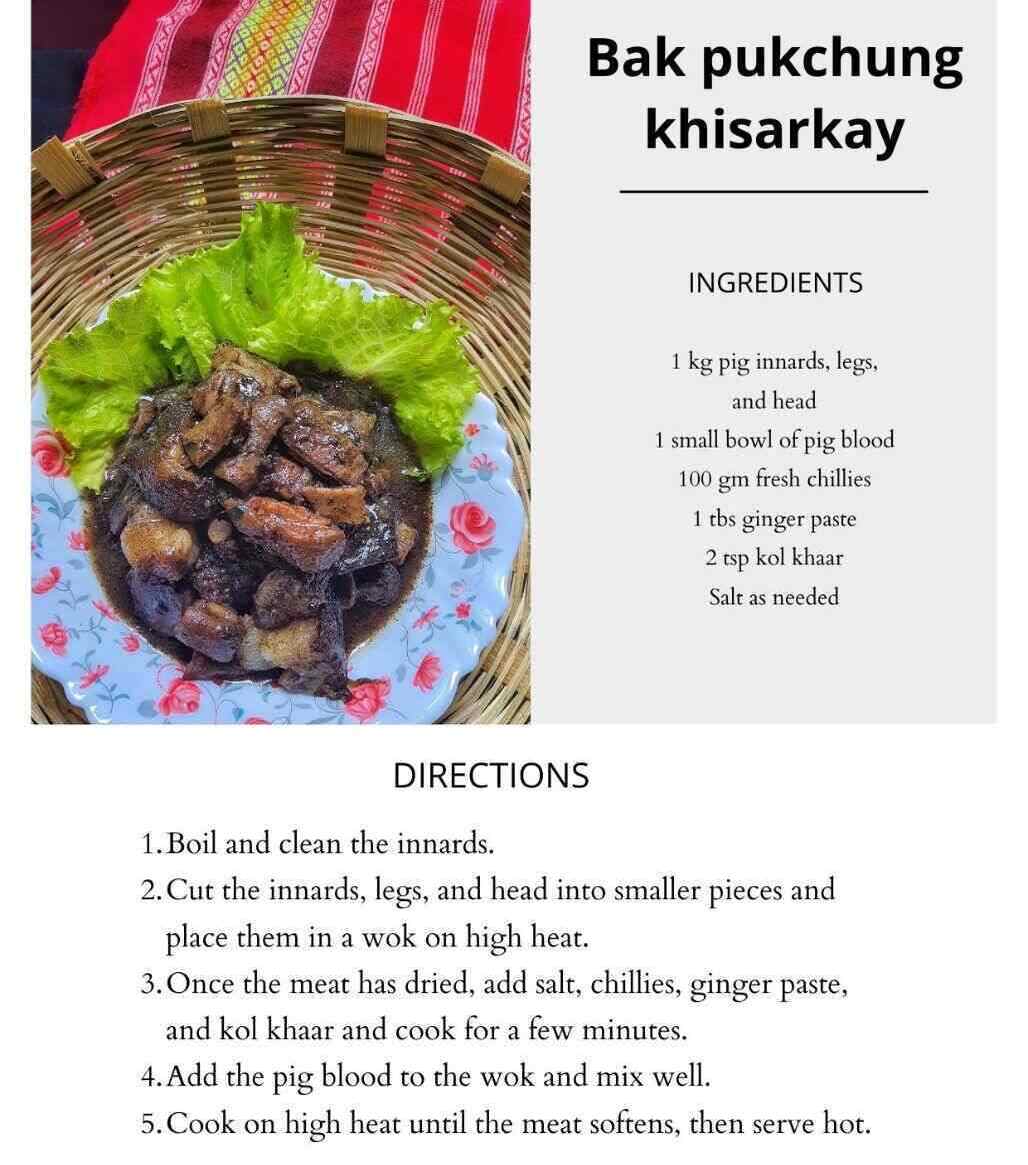

I live in a village in North Garo Hills district, Meghalaya. In the Rabha community that I come from, food is cooked without oil. I believe the reason for this is that we consume meat for all our meals. Seasonal herbs and meat made up our diet; unlike the rest of India, until recently dal wasn’t a part of our cuisine. People often tell us that it is unhealthy to eat so much meat because of the fat content. However, what they do not realise is that when we cook the meat without oil, we are balancing out the fat that it carries.

The ingredients that the Rabhas use in their cooking are similar to those used by other communities in Northeast India. Like the Assamese, we use kol khaar (alkaline extract from banana ash). We eat kappa (a fiery meat curry) like the Garos, but we boil the meat instead of frying it and don’t use masalas. However, when you talk about cooking with khaar or eating kappa, people do not instantly think about Rabha food because it isn’t as popular and so they don’t know about it.

I love to cook. During the COVID-19 lockdown, I started a Facebook page and an Instagram page just to share what I cook at home. I was surprised to see how curious people were. I had put up photos of bak pukchung khisarkay (pork curry cooked with pig innards and blood) and other dishes like bak kaka tupay raipram (pork cooked with green or black lentils, banana stem, kol khaar, and rice flour) and to kaka tupay bamchi (chicken cooked with green or black lentils and kol khaar) that they had never seen. I began receiving messages asking about these dishes. Many people wanted me to deliver the food to their homes, which I did for those who lived near my village.

There’s a notion that food should look a certain way. Young people in our community started feeling embarrassed that their food doesn’t look palatable. In fact, many dishes began vanishing from celebrations such as weddings due to this shame. To dismantle this notion, I visit the northeastern states and display Rabha dishes at various fairs. These spaces help Rabha food reach more people, and their appreciation of our cuisine instils a sense of pride and confidence in our youth. I want to document our food in all its authentic forms so that the new generation can continue to cook it. I want to work on a book on Rabha food, but I will need financial support from nonprofits and the government.

Shanti Badaik, Chik Badaik tribe, Odisha

In Odisha’s Sundargarh district, my Chik Badaik community celebrates the Navakhana (new food) festival in October–November when we harvest the grain that we grow. It is a big event with many rituals and lots of food. We flatten rice to make poha (a popular rice dish) and cook all the saag (leafy vegetables) together—mustard leaves, string bean leaves, and everything that grows in our backyards. We boil the saag before cooking, which is different from the practice followed by other communities in Odisha.

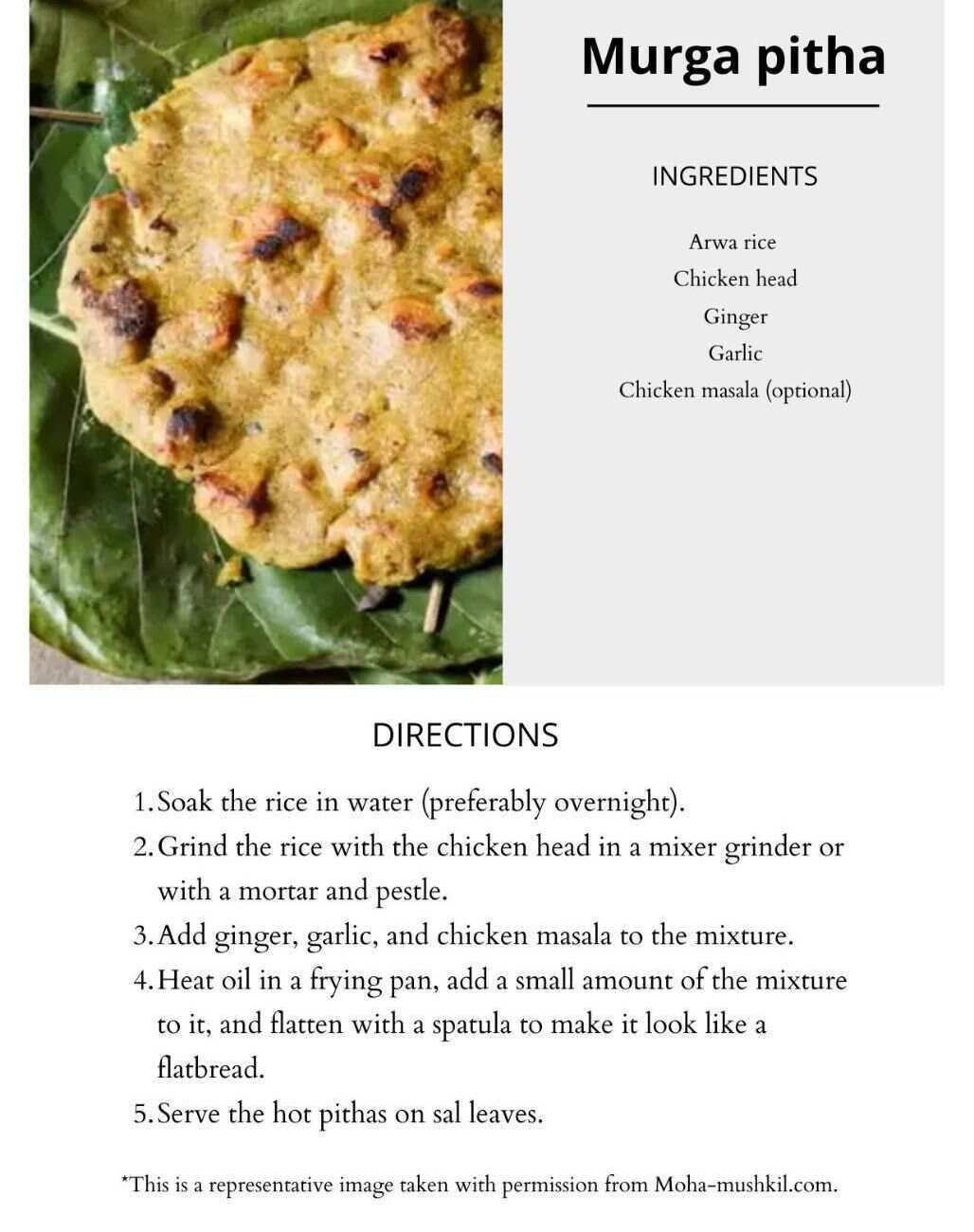

Our Navakhana ritual also includes sacrificing chickens. We buy two or three chickens and perform pujas to our ancestors before sacrificing the birds. After that, we consume all parts of the chicken. We eat murga chawal bhunja (chicken with roasted rice), which is very popular among children, and we also make pitha (pancake) with the chicken head.

For the past four to five years, I have been managing Shanti self-help group. There are 10 women in the group and we focus on cooking, apart from teaching women in the nearby villages about the benefits and various ways of saving money. Our members are hired in cities like Rourkela by people who don’t have the time to cook their meals.

We underwent a training course with Skill India programme to become cooking teachers. We now go from village to village and teach young girls—mostly school dropouts—different recipes and cooking techniques so that, instead of just waiting to get married, they can find sources of livelihood. We teach them innovative recipes such as ragi manchurian, and we also learn from their ways of cooking.

Once they finish their training, they get a certificate from the Skill India programme, which they can use to get loans to start their own micro enterprise. The problem is that not every girl has the courage to go as far as seeking a loan and setting up a business for herself. The government and nonprofits should support these girls even after the programme is over. They could set up a centre for these women to cook together and earn for themselves. Otherwise, these programmes won’t really lead to income generation.

This article was updated on Feb 13, 2023 to correct the spelling of Dwipanita Rabha’s name and the image used for paatbadi.

—

Know more

- Read this article to learn about the lasting legacy of mahua in India.

- Read this article to learn how the trend of ‘organic food’ is doing more harm than good to India’s tribal communities.

- Read this article to learn why undernutrition persists among India’s scheduled tribes.